What Does “Optimal Solution” Really Mean in Coding Interviews? A Guide to Big-O and Efficiency.

Stop getting rejected for slow code. Learn what "Optimal Solution" truly means in coding interviews, master Big-O analysis, and discover the 6-step framework to optimize your algorithms.

If you’ve ever practiced for coding interviews, you’ve probably heard the phrase “optimal solution” more times than you can count.

It pops up in tutorials, mock interviews, and those dreaded follow-up questions from interviewers: “Great… now can you optimize it?”

And that’s where things get tricky.

What is an optimal solution, really?

Is it just the fastest one?

The shortest?

The most elegant?

Or some combination of all three?

The truth is, most people preparing for interviews don’t fully understand what interviewers mean when they ask for a more optimal solution—and it’s not their fault. It does sound simple, but there are certain factors that you need to understand.

This blog is here to change that.

We’ll break down what “optimal” actually means in the world of coding interviews and how to approach optimization without overthinking it.

So, let’s begin.

What Exactly Does “Optimal Solution” Mean?

When an interviewer says “optimal,” they usually mean the best possible solution in terms of efficiency for that problem.

But how do we define “best”?

Here’s the breakdown:

Fastest Running Time

Most often, optimal means the least amount of time complexity.

Every problem has an inherent lower bound on how fast it can be solved (sometimes dictated by the problem’s nature or input size).

For example, if you need to read all inputs anyway, you can’t do better than O(n).

An optimal solution tends to match these lower bounds.

In interview practice, you’ll notice many problems have a brute-force solution and one or two more efficient solutions.

The most efficient one (e.g., O(n) or O(n log n) instead of O(n²)) is considered the optimal solution in the interview context.

One Reddit user summarized it well: often brute force might be O(n²), a “middle” improved solution O(n log n), and the optimal solution O(n) using a clever strategy like hashing.

Minimal Space (if relevant)

Time is king, but space can matter too.

An optimal solution typically also avoids using excessive extra memory unless necessary.

If two approaches have the same time complexity, the one using less memory might be deemed more optimal.

For instance, solving a problem in one pass of an array instead of two might be considered more optimal, even if both are O(n), because it’s doing less work and possibly using less auxiliary space.

However, unless the question specifically emphasizes memory, time complexity is usually the main yardstick.

Meeting the Problem’s Constraints

Optimal also implies it fits within the problem’s limits.

If the input size is huge, a solution that technically has the best Big-O time but with large constants might not be practical.

Interview optimal solutions are generally those that comfortably handle the worst-case input within expected constraints. It’s the solution that fully solves the problem without unnecessary inefficiencies.

To make this concrete, consider a classic example: the Two Sum problem.

A brute-force solution checks every pair of numbers, which is O(n²) time.

A more optimal solution uses a hash map to find complements in O(n) time. That O(n) approach is the optimal solution interviewers are looking for – it’s significantly faster and uses a bit of extra space (the hash map) to save a ton of time.

In fact, one candidate in a Big Tech interview described how they reduced a naive O(N^2 log N) approach down to O(N) using a hash map, which the interviewer confirmed was the optimal solution.

This is a perfect illustration: the best-known complexity for Two Sum is linear, and achieving that made the interviewer happy.

It’s worth noting that optimal doesn’t always mean “unique.” Sometimes more than one approach yields the same top-level complexity.

In that case, any of those approaches is fine.

What matters is that you’ve reached the efficiency that the problem can allow.

Now, that raises a question: are you expected to hit that optimal mark every time?

Let’s discuss.

Do You Always Need the Absolute Optimal Solution?

No, not always – but you should aim for it if you can.

It depends on the interview, the company, and the specific problem.

Here’s the complete view:

Getting the Ball Rolling

In many interviews, it’s perfectly fine (even encouraged) to start with a brute-force or simple solution first.

Why?

It shows you can come up with a correct approach, and it gives you a baseline to improve upon.

Many interviewers will ask, “Can we do better?” after you present an initial solution.

This is a prompt to iterate towards optimality.

You generally won’t be penalized for not blurting out the most efficient solution from the get-go.

In fact, some interviewers might be suspicious if you immediately jump to a very complex optimal solution without a journey, especially if it’s a well-known tricky one – they might wonder if you’ve seen the problem before.

But don’t worry: if you did know it from before, that’s called knowledge, and that’s actually a good thing in an interview!

“Optimal within Reason”

One experienced interviewer put it this way: always shoot for the optimal time complexity within reason.

What does “within reason” mean?

It means that if the optimal solution involves a highly obscure algorithm or a level of math that most wouldn’t know, interviewers might not expect you to pull that out under pressure.

For example, certain problems have ultra-efficient solutions (like using Manacher’s algorithm for the longest palindromic substring in O(n) time) that are not commonly known.

It’s unreasonable to expect every candidate to know that offhand.

Companies want to see you can solve problems, but not every interview question is meant to be finished with a bleeding-edge optimal trick – especially if it’s something that would normally be looked up.

Knowing When “Good Enough” Is Good Enough

Some questions are designed such that an optimal solution is straightforward and expected.

Others intentionally allow multiple levels of improvement.

A solid rule of thumb is to always present a correct solution first (even if it’s not optimal), then discuss how to optimize it.

If you get to a point where further optimization would require something exotic, it’s okay to say, “I believe there is a more efficient approach using [X], but the approach I have now is the most efficient I can derive given the time.”

Interestingly, interviewers often give credit for awareness. One ex-Meta interviewer shared that implementing a “reasonable” solution and then spending a few minutes talking about your intuition for a better solution can score you points – it shows you recognize there’s a better way, even if you didn’t fully implement it.

For instance, you might say, “If I had more time, I’d consider a balanced BST or a trie here to improve the complexity,” which signals you understand the landscape of solutions.

Company Culture and Role Matter

Not all companies emphasize optimal solutions equally.

Big tech companies (FAANG and the like) are known for expecting efficient solutions, because their scale demands it.

Startups or companies hiring for certain roles might be more lenient if your solution is correct and your coding is clean, even if it’s not the most optimal, especially for questions where the optimal solution is very specialized.

That said, aiming high is always good.

One tech lead mentioned that at Meta (Facebook), interviewers commonly push candidates for alternate solutions or deeper optimizations if the initial question was solved easily.

It’s part of how they gauge seniority and depth.

Meanwhile, other interviewers have said they’d be happy if a candidate can explain why a solution can’t be improved further when that’s the case – which means understanding the problem’s boundaries is as important as optimizing.

Bottom line: You won’t necessarily fail for not finding the absolute optimal solution, especially if it’s very hard. But you should demonstrate that you strive for efficiency, and not settle for an obviously slow approach. Show that mindset, and you’ll generally be in good shape.

Next, let’s talk about how you can systematically work toward optimal solutions during your interview.

How to Approach Finding an Optimal Solution (Step-by-Step)

Feeling the pressure to find an optimal solution can be stressful. But if you approach problems methodically, you’ll increase your chances of reaching that efficient answer.

Here’s a step-by-step game plan:

1. Begin with Clarity

Make sure you truly understand the problem. Ask clarifying questions; confirm input/output formats and constraints. Sometimes, hidden in the problem description or constraints is a hint at the expected optimal complexity. For example, if the input size can be up to 10⁶, you know an O(n²) solution will never work – which means you’ll have to think in O(n) or O(n log n) terms.

2. Start Simple (Brute Force)

Yes, start with the “dumb” solution. Outline a brute force approach out loud.

This ensures you have a correct baseline.

Interviewers actually appreciate seeing this because it shows you can derive a solution from first principles. It’s also an opportunity to analyze the weaknesses of that brute force.

Maybe it’s too slow – okay, why?

Identifying where the brute force does redundant or excessive work is the key to unlocking a better approach.

3. Use Patterns and Data Structures

Many optimal solutions come from applying well-known algorithmic patterns or data structures. For instance:

If you see a sorting in the brute force, can you use a HashSet or HashMap to avoid that sorting or nested loop? Using a hash map often turns an O(n²) search into O(n), as seen in many problems (like our Two Sum example).

If brute force checks all substrings or subarrays, perhaps a sliding window or two-pointer technique can cut it down to linear time.

If you’re recursively exploring combinations, maybe dynamic programming (memoization/tabulation) can save repeated work.

Recognize common problem types: for example, traversal problems might need BFS/DFS (and the optimal solution is just doing that efficiently), optimization problems might need DP or greedy strategies, etc.

Practicing patterns is huge – which is why interview prep courses focus on them.

(If you need a refresher on these patterns, check out Grokking the Coding Interview by DesignGurus.io, which is a course entirely about learning the patterns for coding questions. It’s a great way to train your brain to see the optimal solution patterns faster!)

4. Iterate and Optimize Incrementally

Don’t try to leap to a fancy solution in one jump. Instead, improve your approach step by step:

Identify bottlenecks in the brute force. Is there a nested loop that’s driving the complexity up? A recursive call that recalculates the same thing repeatedly? Focus your attention there.

Eliminate redundancies: Perhaps you notice the same sub-problem being solved multiple times. That’s a cue for dynamic programming or memoization. Or you realize you’re scanning the array too many times – maybe you can do it in one pass instead of two.

Use efficient structures: Maybe using a heap, tree, or even a simple array indexing trick could speed things up. A common example: using a min-heap to keep track of the largest or smallest elements can often optimize a problem that naively would sort the entire input. (E.g., find the Kth largest element: sorting is O(n log n), but a min-heap of size K can do it in O(n log K).)

Trade space for time: Many optimal solutions use extra memory to speed up computation. Caching results, using hash sets, etc., all use more space but drastically cut time. This is usually acceptable in interviews unless space is explicitly limited. Always explain this trade-off to show you understand it: “I’m using extra space to get a faster time; for example, storing values in a set to achieve O(n) lookup instead of an O(n) scan each time, trading space for speed.”

As you iterate, communicate your thought process.

Let the interviewer know what you’re thinking: “Okay, the brute force checks every pair – that’s too slow. What if I sort the list first? That could give me O(n log n) which is better. Or perhaps I can use a hash map to jump to the needed values in O(1) time. Let’s try the hash map approach…”

This kind of narration shows you’re systematically working toward an optimal solution, and the interviewer might even guide you if you’re on the right track or not.

5. Recognize the Optimal When You See It

How do you know when you’ve reached an optimal solution?

If you’ve reduced the time complexity to what you suspect is the theoretical minimum (say, linear scan of the input), and further improvements would either break the problem or require unrealistically complex algorithms, you’re probably there.

At this point, it’s crucial to state the complexity of your solution (time and space) and why you believe it’s optimal.

For example: “This approach runs in O(n log n) due to sorting. Given we have to at least look at all n items, we can’t do better than O(n) fundamentally, so O(n log n) is likely the optimal or near-optimal for this problem.”

If your solution is already O(n) and uses a reasonable amount of space, you can be confident it’s optimal unless there’s a known trick.

Just be ready to explain if the interviewer asks, “Why do you think it can’t be improved further?”

6. If Stuck, Discuss Trade-offs and Alternatives

Let’s say you hit a wall and can’t find a more optimal solution in the moment. It happens!

Rather than going silent or panicking, discuss the trade-offs of your current solution and imagine what an optimal solution might look like.

You might say, “I solved it in O(n²). I suspect an optimal solution might use sorting or a different data structure to get to O(n log n) or O(n). One idea: use a trie to efficiently search prefixes, which could speed it up. I’m not fully sure how to implement that under time, but that’s one direction.”

This shows you’re thinking critically about optimal solutions, even if you didn’t land one completely.

Interviewers appreciate this analytical approach – you’re demonstrating awareness, which can sometimes salvage partial credit or even full credit if the rest of your interview was strong.

Tips to Recognize and Deliver Optimal Solutions

Now that we’ve covered the approach, here are some quick-hit tips to keep in mind, especially for beginners and those prepping for interviews:

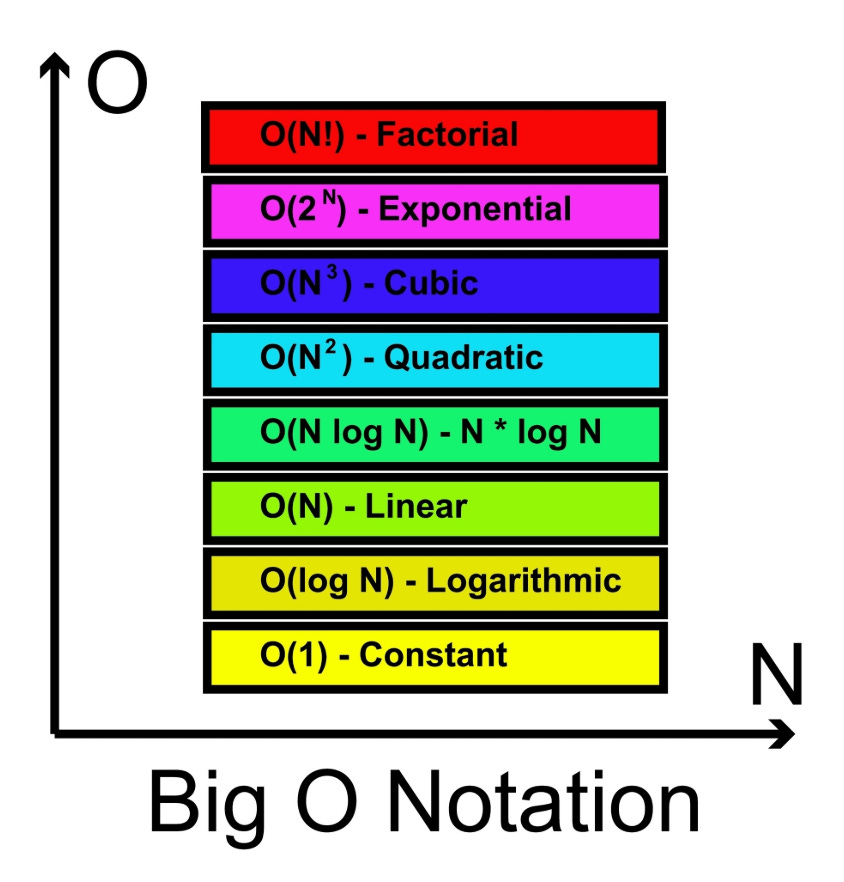

Know Your Complexity Benchmarks: Remember common complexity classes and what they mean for different input sizes. For instance, know that n = 10⁵ or 10⁶ usually demands O(n) or O(n log n) at worst in an interview setting. If your solution is O(n²) for n = 100k, it’s not going to fly – an optimal solution must be found. Keeping these in mind will alert you when your current solution isn’t efficient enough.

Memorize Patterns, Not Answers: Instead of memorizing the solution to 500 LeetCode problems, focus on learning the patterns (two-pointer, BFS/DFS, binary search, dynamic programming, etc.). This builds intuition. When you see a new problem, you’ll start recognizing “aha, this looks like a sliding window scenario” or “feels like a graph traversal problem.” That jumpstarts your path to an optimal approach. Many experts stress pattern recognition over brute memorization. As a resource, Grokking Data Structures & Algorithms for Coding Interviews (another Design Gurus course) is fantastic for reinforcing the fundamental patterns and data structures that lead to optimal solutions. Strengthening those fundamentals will naturally make the “optimal” solutions come to you faster.

Practice Optimizing: It sounds obvious, but practice taking a brute-force solution and improving it. Don’t just stop when you get a solution working. Ask yourself, “Can I make this faster? How would I handle 10x more data?” Websites and courses often present multiple solutions; study the progression from naive to optimal. For example, try solving a problem, then intentionally find a second method to solve it more efficiently. Over time, you’ll internalize the techniques for optimization (caching results, eliminating repeated work, using the right data structure, etc.).

Learn from Hints and Solutions: If you practice and get stuck, read the solution discussions. Pay attention to why a certain approach is optimal. Is it using a certain algorithm (like Dijkstra’s for shortest path, which is optimal for weighted graphs)? Is it exploiting a math trick (like using Gauss’ formula to sum 1..n instead of looping)? Each optimal solution has a reason behind it. Build a mental library of these reasons.

Be Ready to Explain Trade-offs: A truly impressive candidate doesn’t just drop an optimal solution – they explain why it’s optimal and what the trade-offs are. Maybe your optimal uses O(n) time but O(n) extra space, whereas a slightly slower one used constant space. Acknowledge that: “We trade space for time here, which I think is worthwhile. If memory is a concern, there’s an alternative solution that uses no extra space but runs in O(n²), which is obviously not ideal for large input.” This kind of commentary shows maturity in understanding “optimal” isn’t always absolute; it depends on context.

Stay Calm Under Pressure: When the interviewer asks for a more optimal solution, it’s easy to get flustered. Take a breath. Remember, this is part of the process. They expect you to refine your approach. It doesn’t mean your first solution was garbage; it’s just a starting point. Keeping a cool head will help you think clearly. Often, talking through the problem again or stepping back can trigger the realization you need. And if you truly can’t think of anything, be honest about what part is challenging you – sometimes the interviewer will nudge you in the right direction.

Know Common “Optimal” Algorithms: Certain famous problems have well-known optimal solutions (like Kadane’s algorithm for maximum subarray is O(n), or using a stack for next greater element in O(n)). You don’t need to memorize every one by name, but be familiar with them through practice. When you encounter a similar problem, you might recall, “Oh, this reminds me of that stack trick” or “This is similar to that classic DP problem.” Recognizing the connection can lead you straight to the optimal approach.

Finally, remember that interviewers are humans, too.

They know interviews are artificial scenarios.

What they care about is seeing your thought process and problem-solving skills.

Whether or not you land perfectly on the most optimal solution, if you show that you’re striving for efficiency, aware of complexity, and can discuss solutions intelligently, you’ll make a great impression.

Getting Better at Finding Optimal Solutions (Practice Makes Perfect)

Since the intended audience here is beginners, students, and folks prepping for interviews, it’s worth emphasizing: nobody is born knowing this stuff. All those brilliant engineers who can magically conjure the optimal solution likely spent a lot of time practicing and learning from mistakes. So, how can you level up?

Practice, Practice, Practice: There’s no substitute for it. Use platforms like LeetCode, HackerRank, etc., to expose yourself to a variety of problems. When you solve each problem, don’t stop at one solution. Try to implement the more optimal solution, even if you need to peek at hints. Over time, the patterns will stick.

Use Structured Resources: Sometimes random problem solving isn’t enough; a structured course can guide you through patterns systematically.

Simulate the Pressure: Try timing yourself or doing mock interviews. In a timed setting, you’ll get better at quickly deciding when to settle for a “good enough” solution and when to push for more optimization. You’ll also learn how to explain your thought process under pressure – a crucial skill as we discussed.

Learn to Read Constraints: Often interview or problem descriptions include input size limits. Make it a habit to derive from those limits what complexity is acceptable. This skill directly guides you toward the optimal solution space. If you see “n can be up to 10^7”, you immediately know only an O(n) or O(n log n) solution in C++ (or maybe O(n) in Python) will work. If you have multiple loops, you know you must rethink.

Stay Updated on Techniques: The fundamentals don’t change, but occasionally new methods or data structures become common knowledge. For example, a few years back, not many interviewees knew about using a monotonic stack for certain problems – now it’s more common knowledge. If you’re actively preparing, reading interview experiences or solution discussions can clue you in on any “trending” techniques. However, beware of chasing every fancy trick; stick to core patterns first.

By actively building these skills, you’ll find that “optimal solution” starts to feel less like a scary phrase and more like a fun challenge.

Conclusion: Optimal Solutions & You

So, what does “optimal solution” really mean in interviews?

It means the best, most efficient solution you can come up with for the problem – especially in terms of time complexity – given the problem’s constraints.

It’s what you get when you refine a correct solution to eliminate unnecessary work and use the right tools for the job.

Interviewers ask for it not because they demand perfection, but because they want to see how you approach improving a solution and whether you understand what efficiency looks like.

For beginners and interview prep folks, the key takeaways are:

Always aim to improve your first solution if there’s room to improve. It shows initiative and understanding.

Don’t be discouraged if the optimal solution isn’t obvious at first. Talk it out, use systematic techniques, and remember that many others have been stumped and then learned how to get there.

“Optimal” can have caveats – sometimes a near-optimal solution with a good explanation is perfectly fine. Demonstrating awareness of what could be better can sometimes be as valuable as actually coding it up.

Keep practicing and learning. Over time, what once seemed like a clever trick will become second nature to you.

Finally, stay conversational and relaxed in your interviews.

Good luck with your interview prep, and remember: every optimal solution was once a brute-force solution that someone kept improving.