System Design Interview Gold: From OOM Errors to Stable Architectures

Explore the three main strategies for handling backpressure. Learn when to use queues and when to shed load to save your server.

Stability is the single most important feature of any software system.

You can write the most beautiful code and design the most elegant algorithms.

However, if your application crashes the moment a few thousand users log in at once, none of that matters.

When you are learning to code, you usually run programs on your local laptop.

You are the only user.

The data moves instantly.

Nothing ever gets clogged.

In the real world of large-scale systems, data does not always flow smoothly. Sometimes, data arrives like a gentle stream.

Other times, it arrives like a fire hose.

This is where many junior developers struggle during System Design Interviews. They focus on how to process the data, but they forget to ask what happens when there is too much data.

Today, we are going to talk about the safety valve of the internet.

We are going to talk about Backpressure.

The Core Concept

Let’s start with the absolute basics.

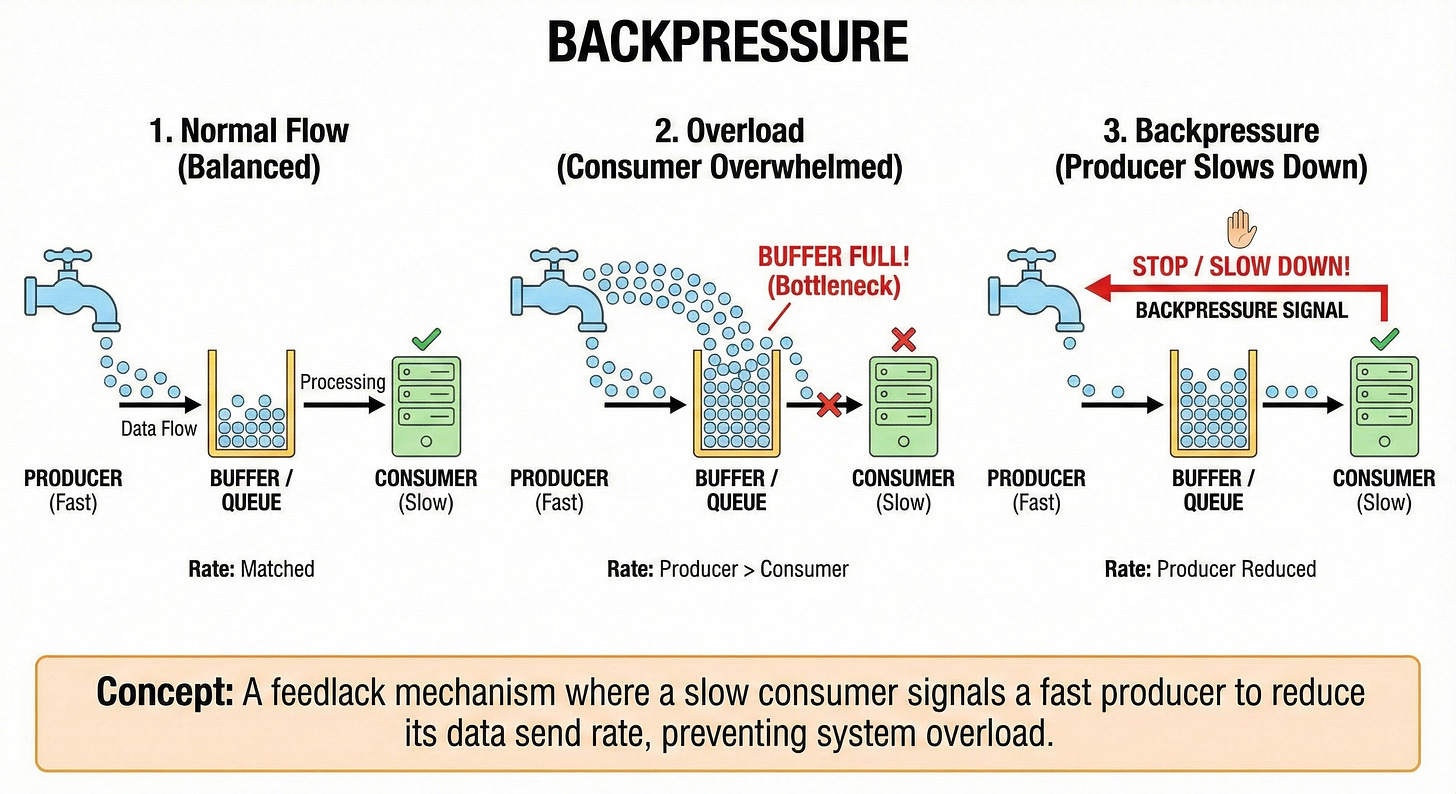

In almost every software system, there is a flow of data. This flow usually involves two main parties.

The Producer: This is the component that generates or sends data.

The Consumer: This is the component that receives and processes that data.

In a perfect world, the Consumer processes data at the exact same speed that the Producer creates it.

Unfortunately, we do not live in a perfect world.

Usually, the Producer is much faster than the Consumer.

Imagine a server receiving millions of clicks (Producer) while a database tries to write them to a hard drive (Consumer).

The clicks come in fast, but writing to a disk takes time.

If the Producer keeps pushing data faster than the Consumer can handle it, the Consumer will eventually crash. It runs out of memory trying to hold onto all that incoming work.

Backpressure is the mechanism that prevents this crash.

It is a feedback system. It allows the Consumer to say to the Producer, “Hey, I am overwhelmed. Please slow down or stop sending data until I catch up.”

The Cake Factory Example

To really understand this, let’s step away from computers for a moment.

Imagine you are working in a cake factory.

You are the Decorator (The Consumer). Your job is to put icing on cakes. It takes you exactly one minute to decorate one cake.

Your friend is the Baker (The Producer). Their job is to bake the cakes and slide them down a conveyor belt to you.

Scenario A: No Backpressure (The Crash)

The Baker is having a great day.

They start baking 5 cakes per minute.

They slide them down the conveyor belt.

You can only finish 1 cake per minute.

In the first minute, 5 cakes arrive. You finish 1.

There are now 4 cakes sitting on your table waiting.

In the next minute, 5 more cakes arrive. You finish 1.

Now there are 8 cakes piling up.

Within ten minutes, your room is full of cakes. You have nowhere to put them. Cakes are falling on the floor. You are stressed out.

Eventually, you are buried under a mountain of sponge cake and you pass out. The factory stops.

This is exactly what happens to a server when it runs out of RAM (Random Access Memory). It crashes.

Scenario B: With Backpressure (Stability)

Now, let’s add a backpressure mechanism.

We install a red light and a green light at the Baker’s station. You have a button at your table.

The Baker starts sending cakes. You see three cakes pile up on your table. You hit the button. The light turns Red.

The Baker sees the red light and stops baking. They take a break.

You spend the next three minutes finishing those three cakes.

Once your table is clear, you hit the button again.

The light turns Green. The Baker starts working again.

The factory produces fewer cakes overall, but no cakes fall on the floor and you do not pass out. The system is stable.

That signal, the red light, is backpressure.

Strategies for Handling Backpressure

In software, we cannot always just install a red light.

We have to write code to handle these situations.

When a system is under heavy load, there are three main strategies we use to apply backpressure.

1. Control (Blocking or Throttling)

This is the most direct form of backpressure. It works exactly like the cake factory example.

When the Consumer is busy, it refuses to accept new work.

If you are sending data over a network connection, the Consumer might stop reading from the network socket. This forces the Producer to wait.

In a synchronous system (where the Producer waits for a reply), the Consumer might simply delay sending a response. This forces the Producer to sit there and wait before it can send the next request.

Pros:

It is safe. No data is lost.

It is simple to understand.

Cons:

It slows down the Producer significantly.

If the Producer is a user waiting for a webpage to load, they will see a spinning wheel. If it spins too long, they will leave.

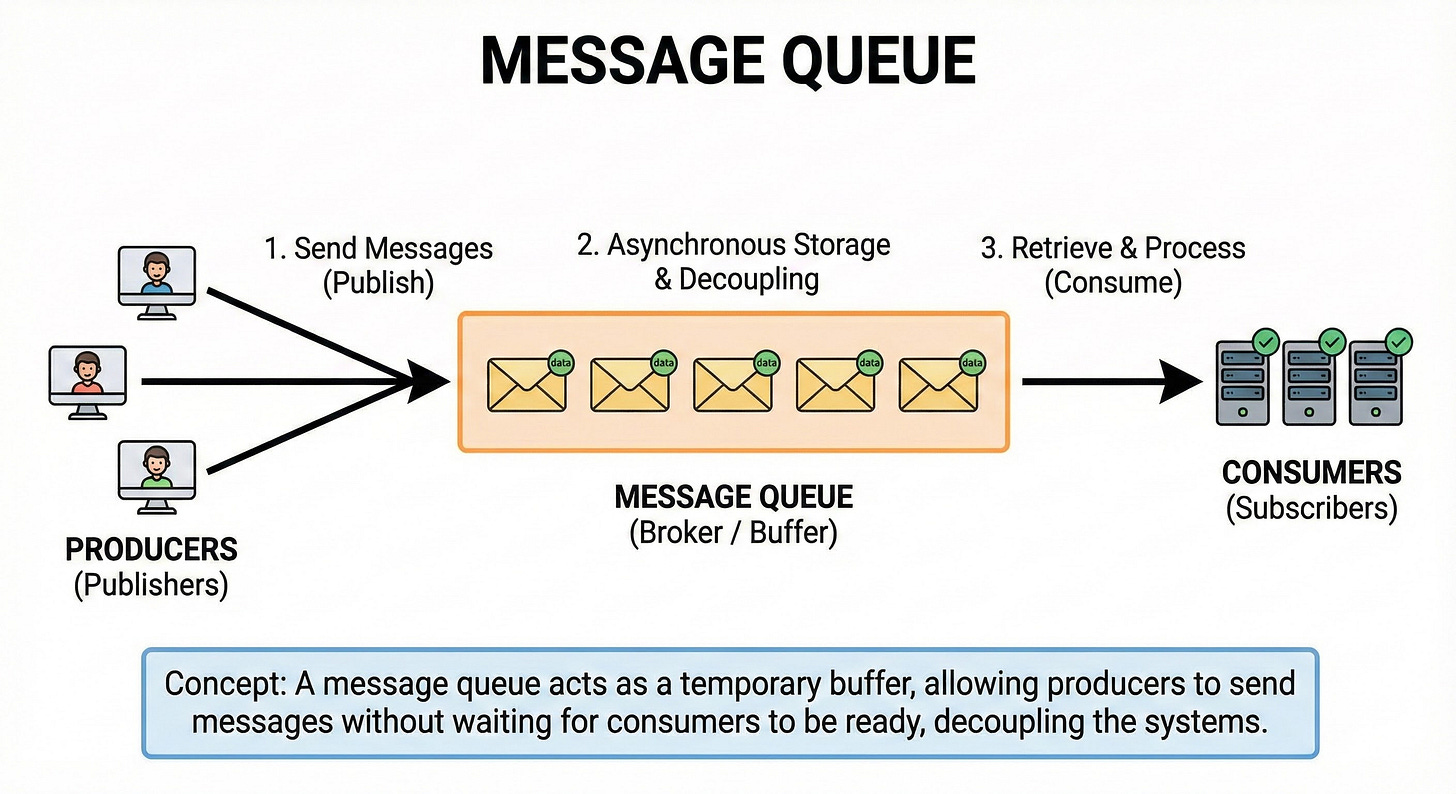

2. Buffering (The Queue)

Sometimes, we know the spike in traffic is temporary. Maybe lots of people log in at 9:00 AM, but it gets quiet by 9:15 AM.

In this case, we can use a Buffer or a Queue.

Think of this as a waiting room.

Instead of the Baker handing the cake directly to you, they place it on a long table. You grab the next cake whenever you are ready.

If the Baker is faster than you for a few minutes, the table fills up.

When the Baker slows down later, you can catch up and empty the table.

The Danger of Buffering:

This is the most common trap for junior developers. They think, “I will just put all the requests in a queue!”

But memory is finite.

If the Baker is always faster than you, the table (Queue) will eventually run out of space.

When the Queue is full, you are back to the original problem. You will get an OOM (Out Of Memory) Error.

You should always set a limit on your buffer size. You need a Bounded Queue. Never use an unbounded queue in production.

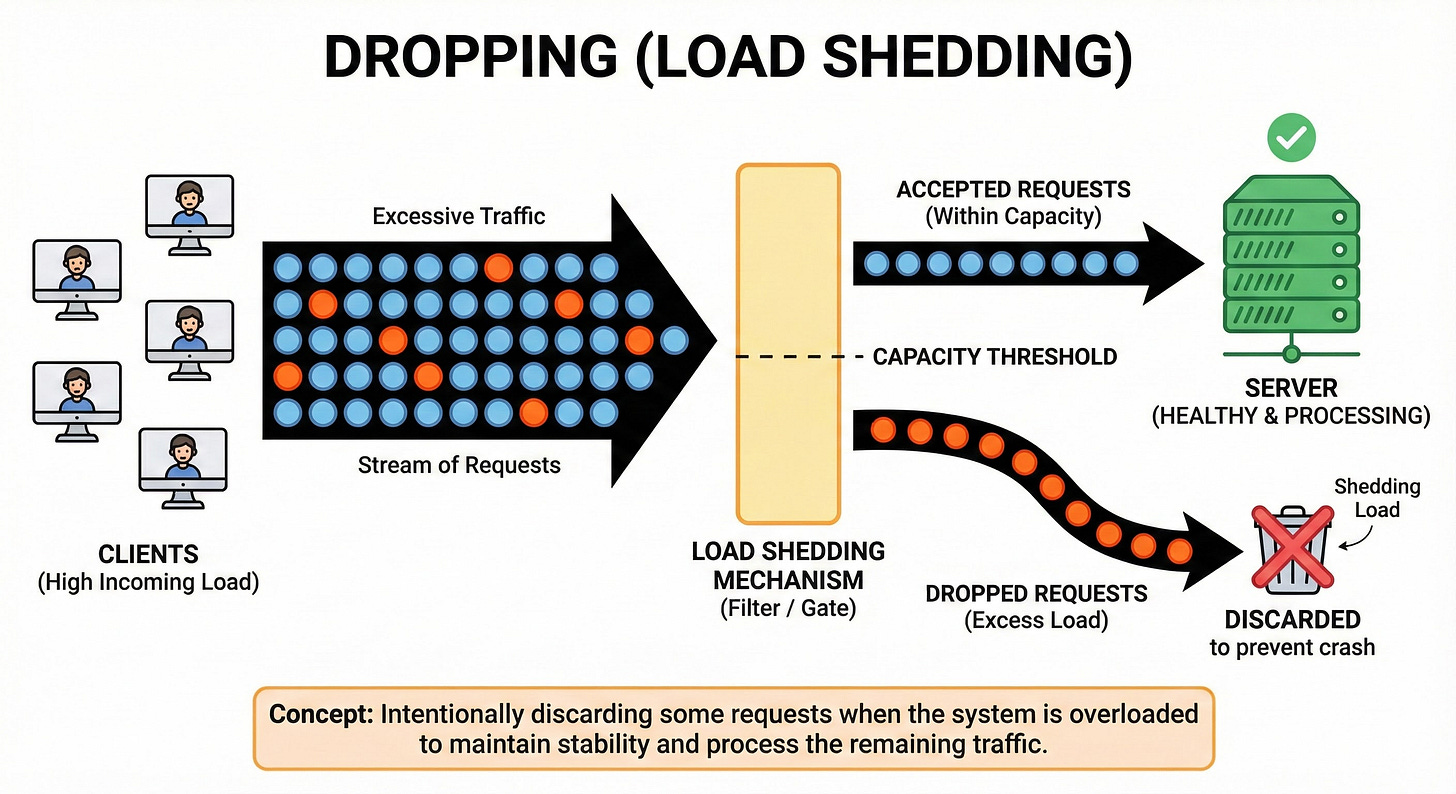

3. Dropping (Load Shedding)

Sometimes, the best way to save the system is to simply say “No.”

If the Consumer is overwhelmed and the buffer is full, the system starts deleting incoming data. This sounds harsh, but it is often necessary.

Imagine a video streaming service.

If your internet connection is slow, you don’t want the video player to pause for 20 minutes to download every single frame you missed.

You want it to just skip the missed frames and show you what is happening now.

There are different ways to drop data:

Drop Newest: Ignore the new data coming in. This is like a bouncer telling new people they cannot enter the club.

Drop Oldest: Delete the old data in the queue to make room for new data. This is useful if fresh data is more important than old data.

Pros:

The system survives and stays fast for the requests it can handle.

Cons:

Data is lost. You cannot use this for things like payment processing.

The Push vs. Pull Debate

To fully grasp backpressure, you need to understand the difference between Push and Pull systems. This is often where the “lightbulb moment” happens for students.

The Push Model: In a standard system, the Producer pushes data as fast as it can. It assumes the Consumer is ready. This is how most junior developers write code initially because it is intuitive. You write a loop that sends requests. The problem is that the Producer is in control, but the Producer does not know the Consumer’s limits.

The Pull Model: In a system with backpressure, we flip the script. The Consumer requests data only when it is ready.

Consumer: “I am ready for 5 items.”

Producer: Sends 5 items.

Consumer: Processes them.

Consumer: “Okay, I am ready for 5 more.”

In this model, the Consumer is in control.

It is mathematically impossible to overwhelm the Consumer because it never asks for more than it can handle. This is the gold standard for resilient system design.

Behind the Scenes: How It Actually Works

You might be wondering how this looks in code or infrastructure.

You do not always have to build this yourself.

Many tools handle it for you.

TCP Flow Control

The internet runs on a protocol called TCP (Transmission Control Protocol). Backpressure is built right into the foundation of the internet.

When your computer downloads a file from a server, your computer has a receive buffer (a bucket).

If the server sends data too fast and fills up your bucket, your computer sends a signal inside the data packets.

It effectively tells the server, “My bucket is full. Reduce your window size.”

The server automatically slows down.

You do not have to write code for this. It happens at the operating system level.

Message Queues (Kafka / RabbitMQ)

In large system designs, we often use message brokers like RabbitMQ or Kafka. These are giant, dedicated buffers.

If a Consumer (like a payment processor) is slow, the messages just pile up in Kafka (which stores them on the hard disk).

Kafka acts as a massive shock absorber.

It holds the backpressure so the Producer does not have to slow down, and the Consumer does not crash.

Why This Matters for Interviews

If you are preparing for a System Design Interview, mentioning backpressure is a “green flag” for interviewers. It shows maturity.

Junior developers design for the “Happy Path” (when everything works perfectly).

Senior developers design for the “Failure Path” (when things go wrong).

When an interviewer asks, “How would you design a system to handle 1 million requests per second?” do not just talk about adding more servers.

You should say something like this:

“We need to consider what happens if our database slows down. We should implement a queue to buffer requests. If the queue fills up, we should have a backpressure mechanism to throttle the users so we do not crash the entire system.”

That answer proves you understand how large-scale architecture actually works.

Conclusion

Backpressure is the art of balancing supply and demand within your software.

It is the difference between a system that gets a little slow on Black Friday and a system that goes completely offline.

Here are the key takeaways to remember:

Producers and Consumers: Systems always have a fast side (Producer) and a slow side (Consumer).

The Problem: If the Producer is too fast, the Consumer runs out of memory and crashes.

The Solution: Backpressure is the feedback signal asking the Producer to slow down.

Strategy 1 (Control): Block the Producer. Make them wait.

Strategy 2 (Buffer): Use a queue to store data temporarily. Always limit the queue size!

Strategy 3 (Drop): Throw away data if the system is too full. Better to lose some data than crash the whole server.

Next time you write code that processes a list of items or handles web requests, ask yourself, “What happens if this list is one billion items long?”

If the answer is “It crashes,” then you know it is time to think about backpressure.