The High Availability Blueprint: Designing Systems That Never Sleep

Master High Availability (HA) for your system design interview. Learn how to eliminate Single Points of Failure using Load Balancers, Database Replication, Active-Active Failover, and Rate Limiting.

When you tap an app icon, you expect it to open. When you send a message, you expect it to be delivered. When you click “Buy Now,” you expect the confirmation email to arrive before you can even switch tabs.

But as a developer, you know the dirty truth: computers are fragile.

Hard drives wear out. Power supplies burn up. Data center cooling systems fail. Backhoes dig up fiber optic cables. Even a stray cosmic ray can flip a bit in memory and crash a server.

In the physical world, if your car breaks down, you pull over and wait for a tow truck. It is an inconvenience. In the digital world, if Amazon or Netflix “breaks down” for even an hour, it makes global news and costs millions of dollars.

So, how do we bridge this gap? How do we build systems that appear to be 100% reliable using hardware that we know is 100% guaranteed to fail eventually?

The answer is a discipline called High Availability.

If you are a student or a junior developer, you might be used to writing code that runs on your laptop. If it crashes, you just restart it. No big deal. But when you move into system design and large-scale architecture, “just restart it” is not an option. You need to build systems that never sleep.

In this guide, we are going to walk through the fundamental techniques engineers use to keep the lights on, no matter what happens behind the scenes.

What is High Availability?

High Availability (HA) is a measure of how long a system is up and running without interruption. It is not just about preventing crashes; it is about masking them so the user never knows they happened.

In the industry, we measure this using “The Nines.”

You will often hear senior engineers or managers talk about “three nines” or “five nines.” They are referring to the percentage of time the system is operational over the course of a year.

Let’s look at what these numbers actually mean in terms of downtime:

99% (Two Nines): Your system is down for about 3.65 days per year. This might be acceptable for a hobby project or an internal tool, but it is catastrophic for a customer-facing business.

99.9% (Three Nines): Your system is down for about 8.76 hours per year. This is the baseline standard for most commercial websites.

99.99% (Four Nines): Your system is down for about 52.6 minutes per year. This is excellent and requires serious engineering effort.

99.999% (Five Nines): Your system is down for only 5.26 minutes per year. This is the holy grail. It is reserved for critical infrastructure like hospitals, aviation, and major financial systems.

Achieving those extra nines gets exponentially harder and more expensive. To move from 99% to 99.999%, you cannot simply buy better computers. You have to change the way you design your entire architecture.

The core philosophy of HA is simple: Assume everything will break, and plan for it.

1. Eliminate Single Points of Failure (The Spare Tire Rule)

If you take only one concept away from this article, let it be this: Single Points of Failure are the enemy.

A Single Point of Failure (SPOF) is any component in your system that, if it fails, causes the entire system to stop working.

Imagine you are driving a car on a lonely highway. You have four tires. If one pops and you do not have a spare, your journey is over. That tire was a single point of failure. But if you have a spare tire in the trunk, a blowout is just a temporary annoyance. You swap it out and keep moving.

In the world of software, a single server is a car with no spare tire.

If you run your application on one machine, you are gambling. When that machine’s power supply dies, your business dies with it.

To achieve High Availability, we use Redundancy.

Redundancy means duplicating critical components. Instead of one web server, we run two. Instead of one database, we run a primary and a backup. We remove the SPOF by ensuring that if Component A fails, Component B is standing by to take its place.

This sounds simple, but it introduces a new problem. If you have two web servers, they have two different IP addresses. How does the user know which one to connect to? And how do we ensure they don’t connect to the broken one?

This leads us to our next technique.

2. Load Balancing

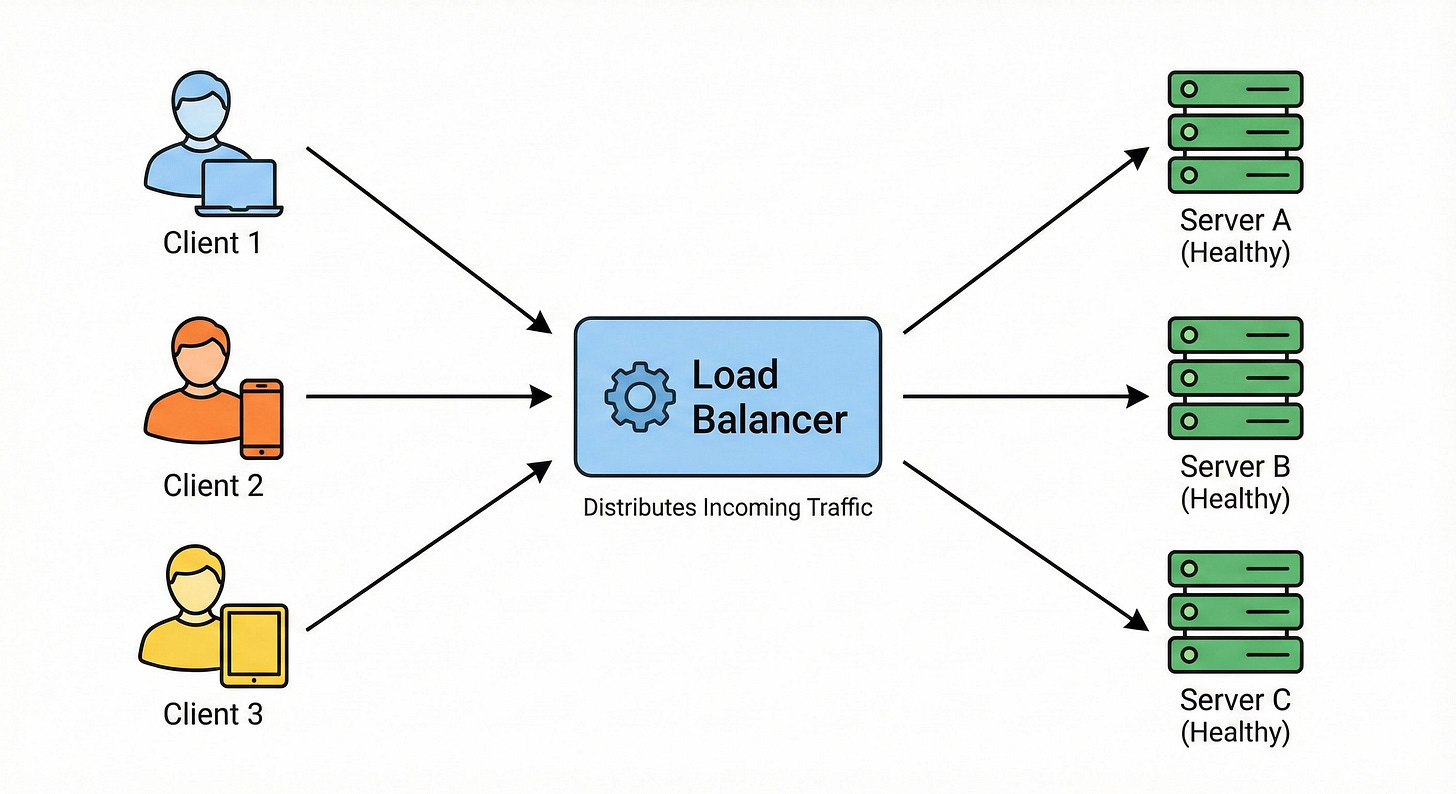

A Load Balancer is a device (or a piece of software) that sits between your users and your servers.

Think of a Load Balancer as a traffic police officer standing at a busy intersection. Cars (users) drive up to him. He points them down different roads (servers) to keep traffic flowing smoothly.

“You, go to Server A.”

“You, go to Server B.”

“You, go to Server C.”

This distribution of traffic ensures that no single server gets overwhelmed. But for High Availability, the Load Balancer performs an even more critical function: Health Checks.

The Traffic Cop isn’t just blindly waving cars through. He is also looking down the road. If he sees that the bridge on Road B has collapsed (Server B crashed), he stops sending cars that way. He directs all traffic to Road A and Road C.

In technical terms, the Load Balancer pings your servers every few seconds.

“Server A, are you there?” -> “200 OK.”

“Server B, are you there?” -> “Error: Connection Timed Out.”

As soon as Server B fails to respond, the Load Balancer removes it from the rotation. The users currently on the site might notice a tiny blip, but new users will simply be routed to the healthy servers. They will never see an error page.

This happens automatically and instantly. This is how we survive server failures.

3. Database Replication

Doubling your web servers is relatively easy because they are usually “stateless.” They don’t store permanent data. If a web server dies, you don’t lose anything important; you just spin up a new one.

But what about your database?

The database holds your users’ accounts, their orders, and their messages. It is “stateful.” If your database hard drive melts, that data is gone forever. You cannot just restart it.

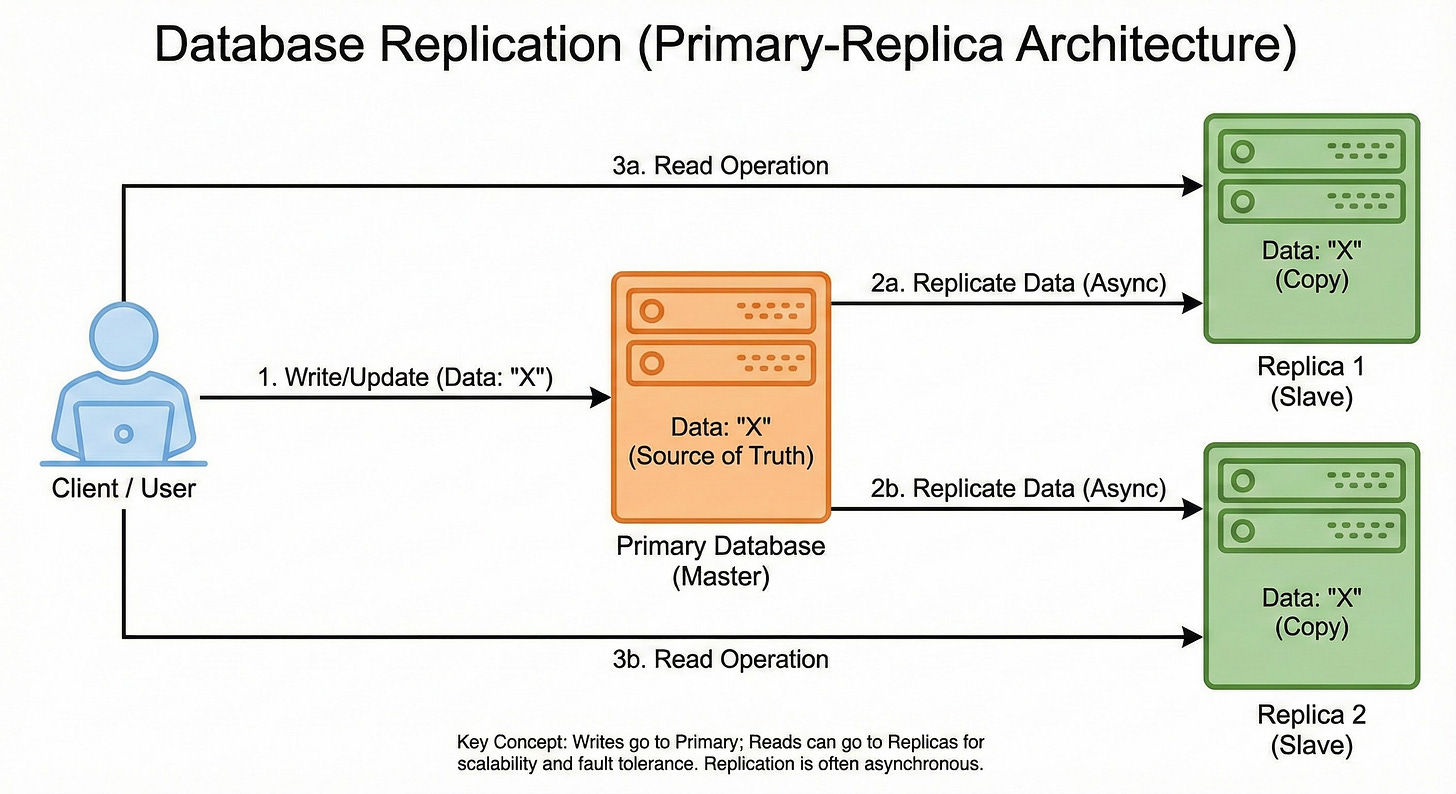

To make a database Highly Available, we use Replication.

Replication is the process of copying data from one database to another in real-time.

The most common pattern for beginners to understand is the Leader-Follower (or Master-Slave) Architecture.

Here is how it works:

The Leader (Master): This is the boss. All new data (writes) must go here. If you create a new user profile, that command is sent to the Leader.

The Follower (Slave): This is the assistant. It constantly watches the Leader. Every time the Leader writes down a piece of data, the Follower copies it into its own notebook.

Now, if the Leader database crashes, we don’t panic. We have a Follower that has an exact copy of the data.

The system detects the crash and promotes the Follower to be the new Leader. This process ensures that your data survives even if the hardware holding it is destroyed.

4. Failover Strategies (The Backup Plan)

We have talked about having redundant servers and databases. But how exactly do we switch from the broken one to the working one?

This process is called Failover.

Failover is the mode of operation where a secondary component takes over when the primary component fails. There are two main ways to architect this.

Active-Passive (Cold/Warm Standby)

Think of this like a generator for your house.

Active: You are normally connected to the city power grid. It does all the work.

Passive: You have a generator sitting in your garage. It is off. It burns no fuel.

If the city power goes out, the generator detects the failure, starts up, and provides power.

In software, you have a Primary Server handling all 100% of the traffic. You have a Secondary Server that sits idle, just waiting for a signal.

Pros: It is simple. There is no risk of data conflicts because only one server is working at a time.

Cons: It is wasteful. You are paying for a Secondary server that does nothing 99% of the time.

Active-Active (Hot Standby)

Think of this like a multi-engine airplane.

Active: Engine 1 is running at 50% power.

Active: Engine 2 is running at 50% power.

They work together to fly the plane. If Engine 1 fails, Engine 2 throttles up to 100% to carry the load.

In software, both servers are handling traffic simultaneously. The Load Balancer splits the users between them.

Pros: You get your money’s worth. You utilize all your hardware.

Cons: It is complex. You have to ensure that if one server fails, the remaining server is powerful enough to handle the entire load alone. If it isn’t, the remaining server will also crash, causing a total outage.

For junior developers, starting with Active-Passive for databases and Active-Active for web servers is a very common and solid pattern.

5. Rate Limiting

Sometimes, your system goes down not because of a hardware failure, but because it is too popular.

Imagine you launch a new viral feature.

Suddenly, 50,000 users try to log in at the exact same second.

Your servers have a limit.

They can only handle so much.

If the traffic exceeds that limit, the servers will run out of memory (RAM) or CPU power and crash.

When they crash, they restart. But the users are still there, so they crash again immediately. This is called a “Cascading Failure.”

To prevent this, we need to defend our system.

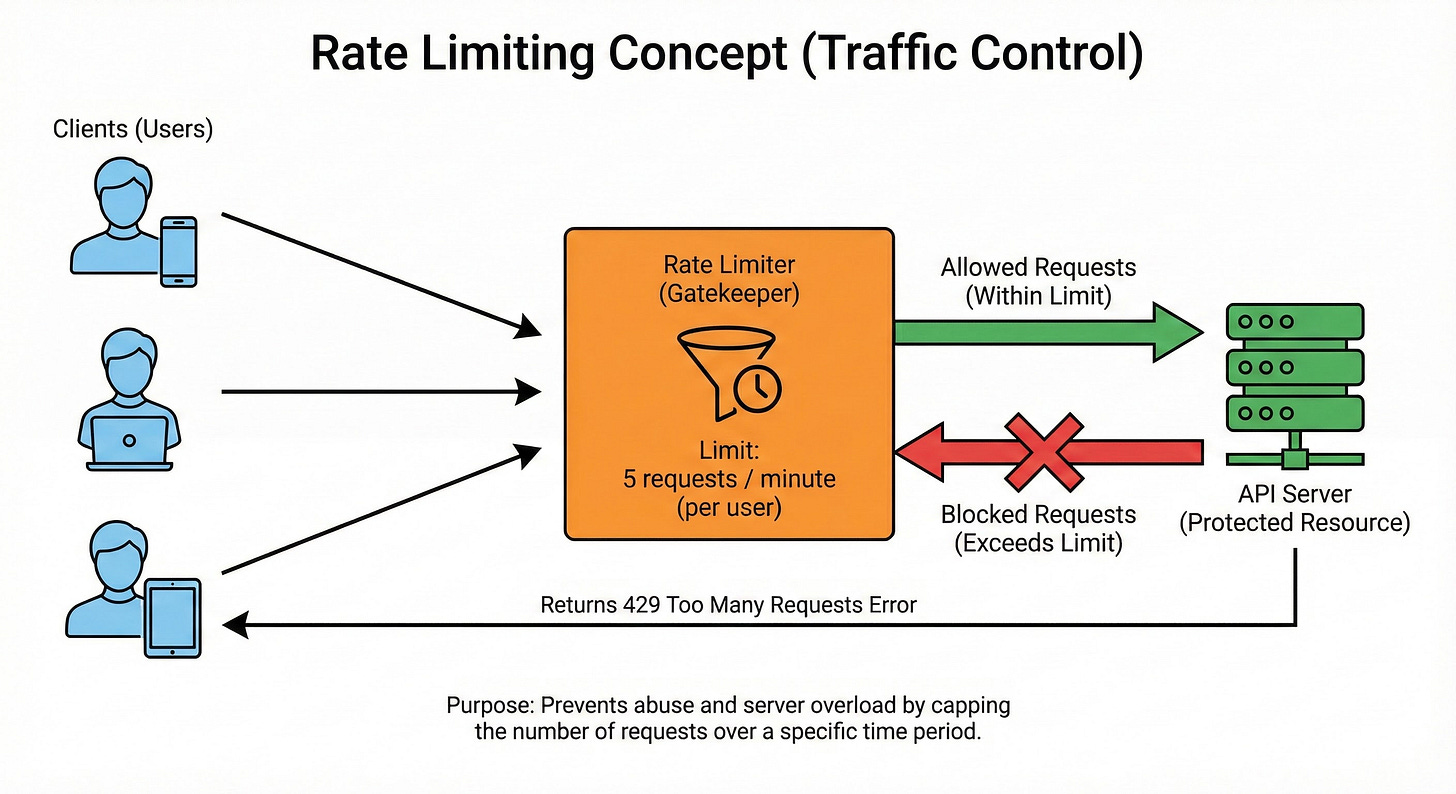

We use Rate Limiting.

Rate limiting is a traffic control strategy that restricts the number of requests a client can make to a server within a specific time window.

Enforcing these caps prevents system overload, protects against abuse like DDoS attacks, and ensures fair resource access for all users.

In code, we set rules:

“A user can only make 60 requests per minute.”

“The system can only accept 10,000 requests per second total.”

If a user tries to make the 61st request, the system blocks it. It returns an error message (HTTP 429: Too Many Requests).

By rejecting the excess traffic, we ensure the server stays alive for the legitimate users who are already inside. It is better to reject a few users than to let the server crash for everyone.

6. Geographic Distribution

You have set up redundant servers.

You have a load balancer.

You have replicated databases.

You are feeling good.

But you put all of these machines in the same building.

What happens if there is a fire?

What if a flood hits the city?

What if the power grid for the entire region goes down?

Your system goes offline.

You still have a single point of failure: The Location.

To achieve the highest levels of availability (those coveted Five Nines), big tech companies use Geographic Distribution.

They do not just run servers in one data center. They run them in multiple regions around the world.

Region A: US East (Virginia)

Region B: US West (Oregon)

Region C: Europe (Dublin)

A global traffic manager (usually a smart DNS service) directs users to the nearest region.

If a hurricane hits Virginia and knocks out the entire US East data center, the traffic manager automatically reroutes all those users to US West.

The site might load a little slower because the data has to travel further, but it works. And in the world of High Availability, a slow site is infinitely better than a down site.

Conclusion

Building a High Availability system is about shifting your mindset. You stop hoping that things will work and start assuming that they will break.

It is a pessimistic way to view hardware, but an optimistic way to view software. By acknowledging that failure is inevitable, we can design systems that are resilient, robust, and reliable.

Here are the key takeaways to remember for your next system design interview or project:

Redundancy is King: Two is one, and one is none. Always have a backup.

Eliminate Single Points of Failure: Identify the components that would kill your system if they died, and duplicate them.

Load Balancers are Essential: They act as traffic cops, routing users away from broken servers.

Replicate Data: Web servers are easy to replace; data is not. Keep copies of your database.

Active-Active vs. Active-Passive: Decide if you want your backups to be working (Active) or waiting (Passive).

Rate Limiting: Protect your system from its own success by capping traffic spikes.

Think Globally: If you can, spread your servers across different physical locations to survive local disasters.

System design is a journey. You don’t need to implement all of this for a personal portfolio site. But understanding these concepts is what separates a coder from a software architect.

Excellent breakdown of HA fundamentals. The traffic cop analogy for load balancers is spot on, but what really clicked for me was teh active-active vs active-passive distinction mapped to airplane engines versus backup generators. In production I've seen teams default to active-passive for simplicity then hit scaling walls when thier passive nodes can't handle full load during failover. The cascading failure risk from rate limiting gaps is real too.