System Design Interview: The Life of a 404 Error

Master the classic system design question: "What happens when you type a URL?" Trace the journey of a 404 error through DNS resolution, TCP/TLS handshakes, CDNs, Load Balancers, and Database lookups.

The internet relies on a complex web of interactions to function.

When a user navigates to a website, they expect an immediate result.

Usually, this result is the content they requested, such as a video, a news article, or a user profile. However, there are times when the requested information simply does not exist.

In these moments, the screen displays a “404 Not Found” error.

To the average user, this represents a failure or a broken link.

To a systems engineer, however, a 404 error is not a failure. It is the result of a perfectly executed chain of events. It signifies that the infrastructure successfully received the request, understood it, routed it across the global network, searched the required data structures, and confirmed with absolute certainty that the resource is missing.

Understanding the lifecycle of a 404 error is a critical exercise for junior developers and system design students. It forces you to examine the entire technology stack without the distraction of complex business logic or rendering engines.

By tracing the path of a failed request, you learn how distributed systems handle discovery, routing, latency, and data retrieval.

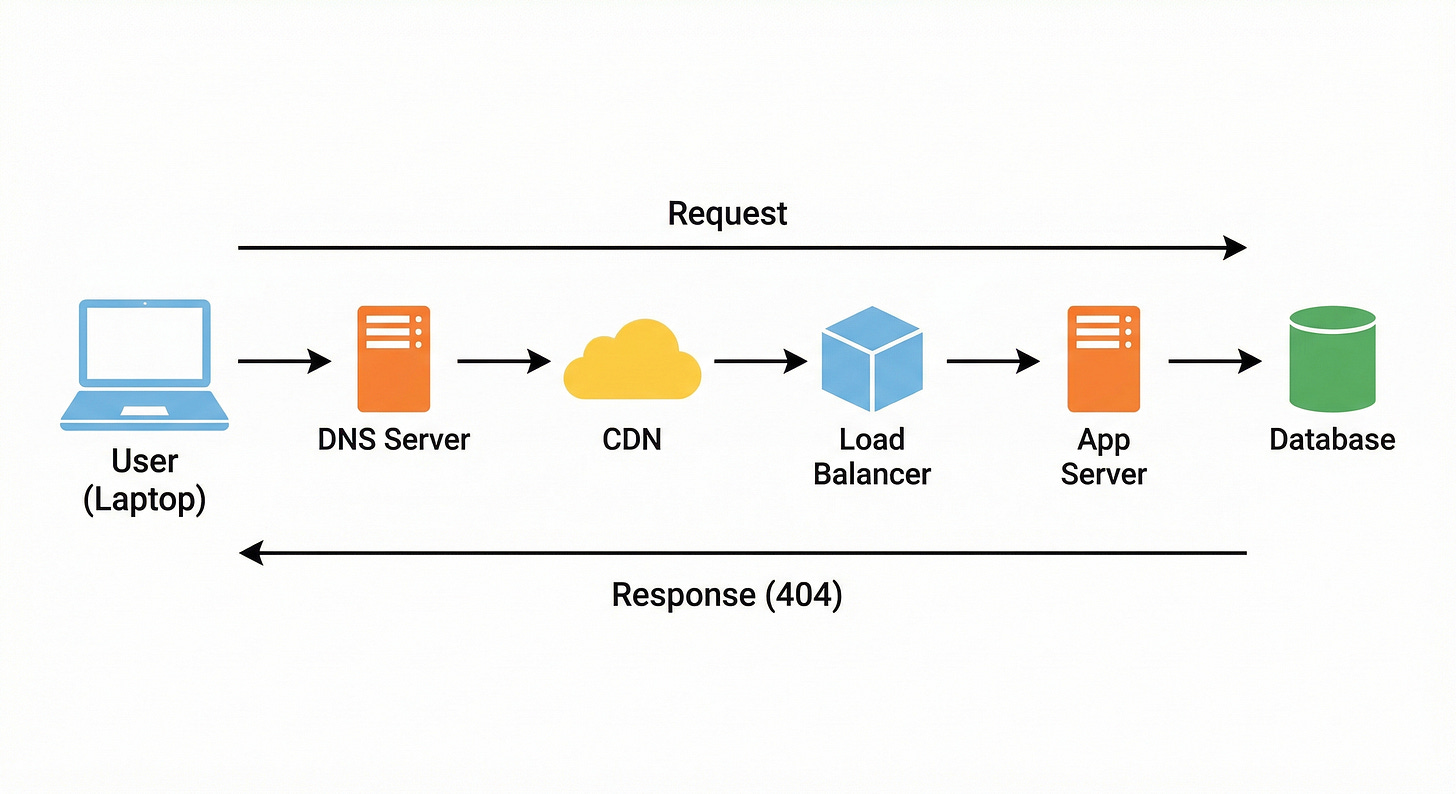

This post will trace the technical journey of a request for a non-existent resource.

We will examine every step, from initial DNS resolution to final database lookup, to understand how modern architectures maintain stability and performance even when the outcome is an error.

Step 1: Address Resolution (DNS)

The journey begins when a user enters a Uniform Resource Locator (URL) into their browser.

The URL contains a domain name and a path. For this explanation, assume the domain is valid, but the path points to a resource that has been deleted or never existed.

Before the browser can send any data, it must locate the server hosting the website.

Networking equipment and servers do not communicate using human-readable domain names. They rely on Internet Protocol (IP) addresses, which are numerical labels assigned to every device on a network.

The process of translating a domain name into an IP address is known as Domain Name System (DNS) resolution.

The Local Cache Hierarchy

The browser attempts to resolve the address as quickly as possible. It first checks its own local memory.

If the user has recently visited this domain, the IP address will be stored in the browser’s DNS cache.

If the record is found here, the lookup process ends immediately.

If the browser cache is empty, the request is passed to the operating system.

The operating system also maintains a cache of recent DNS queries. This multi-layered caching strategy is designed to reduce network traffic and improve load times.

The Recursive Resolver

If the local caches do not hold the answer, the operating system sends a query to a Recursive Resolver. This server is typically managed by the Internet Service Provider (ISP).

The Recursive Resolver is responsible for finding the correct IP address by navigating the hierarchical structure of the internet.

Root Nameservers: The resolver first queries a Root Nameserver. These servers sit at the top of the DNS hierarchy. They do not know the specific IP address of the website, but they know the location of the Top-Level Domain (TLD) servers.

TLD Nameservers: The Root server directs the resolver to the TLD server corresponding to the domain’s extension (such as .com, .org, or .io).

Authoritative Nameservers: The TLD server directs the resolver to the Authoritative Nameserver. This server is the final source of truth for the domain. It holds the specific DNS records configured by the website owner.

The Authoritative Nameserver returns the IP address to the Recursive Resolver, which passes it back to the operating system, and finally to the browser.

The browser now has the destination address required to initiate a connection.

Step 2: Establishing a Secure Connection

With the IP address identified, the browser must establish a connection with the server. Modern web standards require this connection to be reliable and secure.

This involves two distinct phases: the TCP Handshake and the TLS Handshake.

The TCP Handshake

The Transmission Control Protocol (TCP) is the standard used to ensure reliable delivery of data packets. To open a connection, the client and server engage in a three-step exchange:

SYN: The client sends a packet with the SYN (Synchronize) flag set. This signals a request to open a connection.

SYN-ACK: The server receives the request and responds with a packet containing both SYN and ACK (Acknowledge) flags. This confirms receipt and indicates readiness.

ACK: The client sends a final ACK packet.

Once this exchange is complete, a logical connection exists. The system guarantees that data sent through this connection will arrive in the correct order.

The TLS Handshake

Because the web relies on HTTPS for security, the connection must be encrypted. The Transport Layer Security (TLS) protocol handles this.

The browser and server initiate a TLS handshake to negotiate encryption parameters. The server sends its digital certificate to the browser. The browser validates this certificate against a list of trusted Certificate Authorities to ensure the server is who it claims to be.

Once validated, the client and server use asymmetric encryption to exchange a unique session key.

This key is used to encrypt all subsequent data transmitted during the session.

This ensures that the request, and the eventual 404 response, cannot be read by any intermediate devices.