7 System Design Anti-Patterns That Scream “Mid-Level Engineer”

Learn the top system design anti-patterns that reveal a mid-level mindset and discover how to elevate your architectural skills in modern-day software engineering.

Software systems face massive stress when web traffic suddenly increases. Applications freeze and servers crash under heavy processing load.

This scaling problem causes severe downtime and massive revenue loss for digital businesses. Understanding how to build highly resilient systems is the core purpose of software architecture.

Engineers often rely on quick technical fixes to keep struggling applications running. These quick fixes work temporarily but introduce deep structural flaws into the codebase.

These hidden flaws are known as anti-patterns.

System design interviews easily expose these weak architectural choices during technical discussions.

Moving past an average engineering level requires recognizing these hidden traps immediately. True architectural mastery involves understanding the mathematical and physical hardware limits of computer servers.

Building highly scalable software demands intentional planning and deep technical insight from the very beginning.

Anti-Pattern 1: Defaulting to Microservices Prematurely

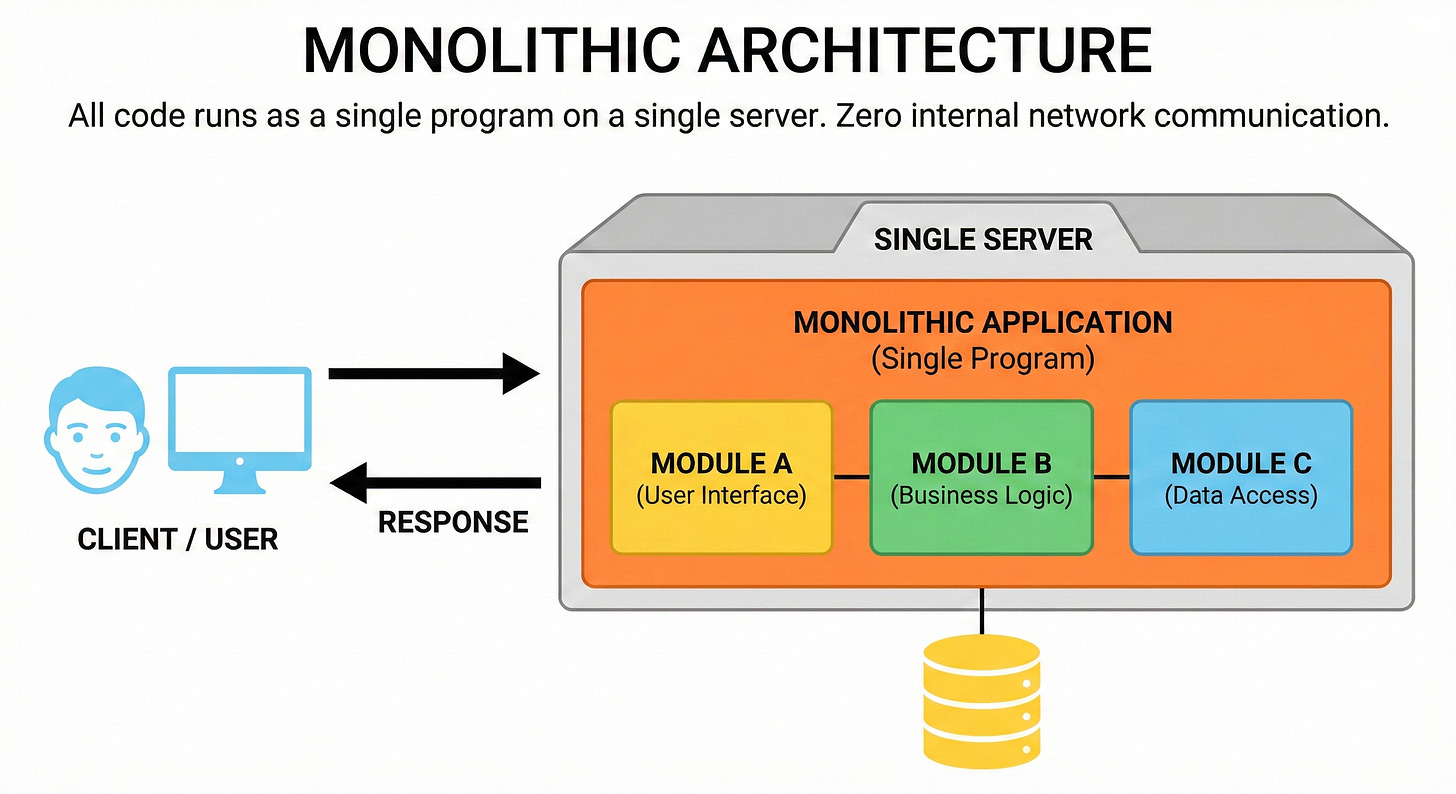

A monolithic architecture bundles all application code inside one single deployable package. All logic runs within the same memory space on the server.

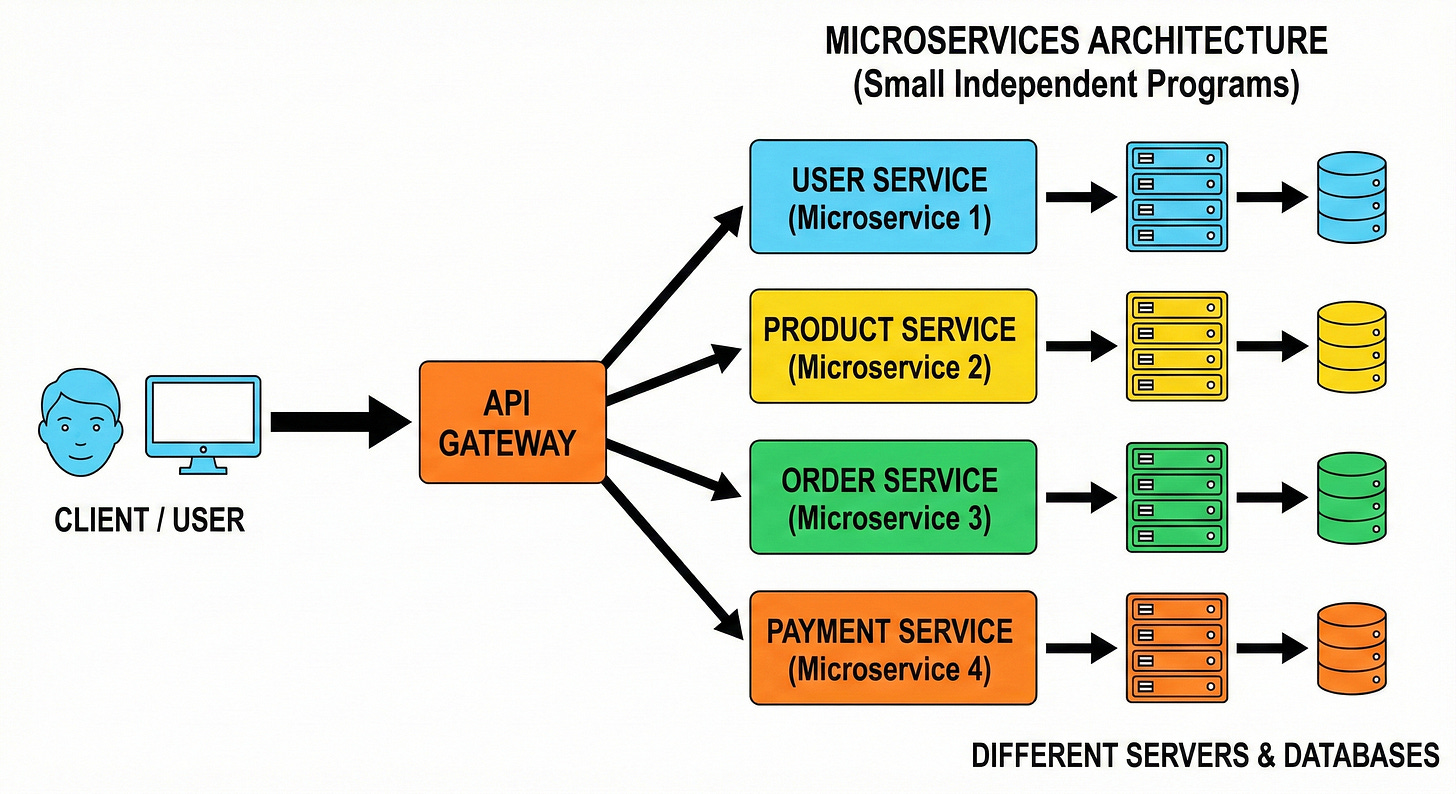

Microservices split a single large application into many small independent programs. Each small program handles one specific technical domain securely. These small programs run on separate physical servers and communicate over a network.

The Mid-Level Crutch

Candidates often slice a basic application into dozens of small services immediately. They assume separating code automatically creates a highly scalable system. They believe this division is the only modern way to build robust software.

This choice introduces massive operational complexity right from the start.

Behind the scenes, sending data across a network is always slower than sending data within a single computer processor.

This physical delay is called network latency.

When five different services must communicate to load one data payload, the application becomes incredibly slow. Every network routing step adds processing time and increases the chance of a dropped connection.

Furthermore, testing a decentralized system becomes a massive engineering hurdle.

Developers must start ten different applications locally just to verify a simple code change. Tracking errors across multiple network boundaries requires highly complex monitoring tools. The infrastructure costs also multiply rapidly since each service requires its own dedicated hosting environment.

The Staff-Level Reality

Senior engineers often start with a cleanly structured monolithic codebase. They establish strict internal boundaries within the code without adding external network complexity. They rely on strict performance metrics rather than early assumptions. They only extract a specific feature into a microservice when that exact feature requires entirely different server hardware.

They extract only computationally heavy data transformations while keeping the rest of the application unified.

This keeps the infrastructure simple, fast, and highly efficient. The deployment pipeline remains straightforward and easy to manage. When the monolithic system finally hits absolute physical hardware limits, the transition to microservices happens organically and safely.

Anti-Pattern 2: Using Caches to Mask Slow Database Queries

A cache is a temporary storage layer that keeps frequently accessed data in fast computer memory. Reading data from active memory is significantly faster than searching a large permanent hard drive.

Caching reduces the processing load on the main database system. It acts as a high-speed protection layer for backend storage servers.

The Mid-Level Crutch

Engineers frequently add a caching box to their diagrams whenever a system appears slow. They treat caching as a quick structural fix for poorly optimized database searches. They assume placing temporary memory in front of a database fixes all performance issues immediately.

This approach ignores the immense difficulty of keeping the temporary data accurate.

When the main database updates a record, the temporary cache often still holds the old data. This creates a dangerous state of inconsistent information across the application. Engineers must write complex rules to update the cache simultaneously.

This automated update process is called cache invalidation.

If the invalidation logic fails, client applications receive completely outdated information. The underlying database query remains terribly slow and unoptimized underneath the cache.

When the temporary memory eventually restarts or clears, the slow database immediately crashes under the sudden massive load. This creates a highly fragile software architecture.

The Staff-Level Reality

Top engineers optimize their underlying database structures first before adding new memory layers. They analyze the slow search queries to identify missing search pathways. They create a database index to speed up searches natively on the hard drive.