50 System Design Concepts for Beginners in 90 Minutes [2026 Edition]

Learn 50 essential system design concepts in one place - scaling, CAP/PACELC, sharding, caching, queues, reliability patterns, and security. A fast, practical primer for beginners and interview prep.

When you start learning system design, the hardest part is not the concepts themselves.

It is figuring out where to find clear explanations in one place.

That is why having a single guide that covers all the essentials is such a game-changer.

Therefore, we have designed this guide to cover 50 of the most important system design concepts.

Think of it as your one-stop reference for understanding how real systems scale, stay reliable, communicate, and handle data.

My goal is to walk you through fifty important ideas using short explanations and simple examples so everything clicks quickly.

I. Core Architecture Principles

Vertical vs Horizontal Scaling

Vertical scaling means upgrading a single machine, like adding more CPU, RAM, or faster storage.

Horizontal scaling means adding more machines and spreading work across them.

Vertical is easier but hits hardware limits and becomes expensive.

Horizontal is harder because you need load balancing, stateless services, and shared storage.

Think of it this way: vertical is one superhero getting stronger, horizontal is building a team.

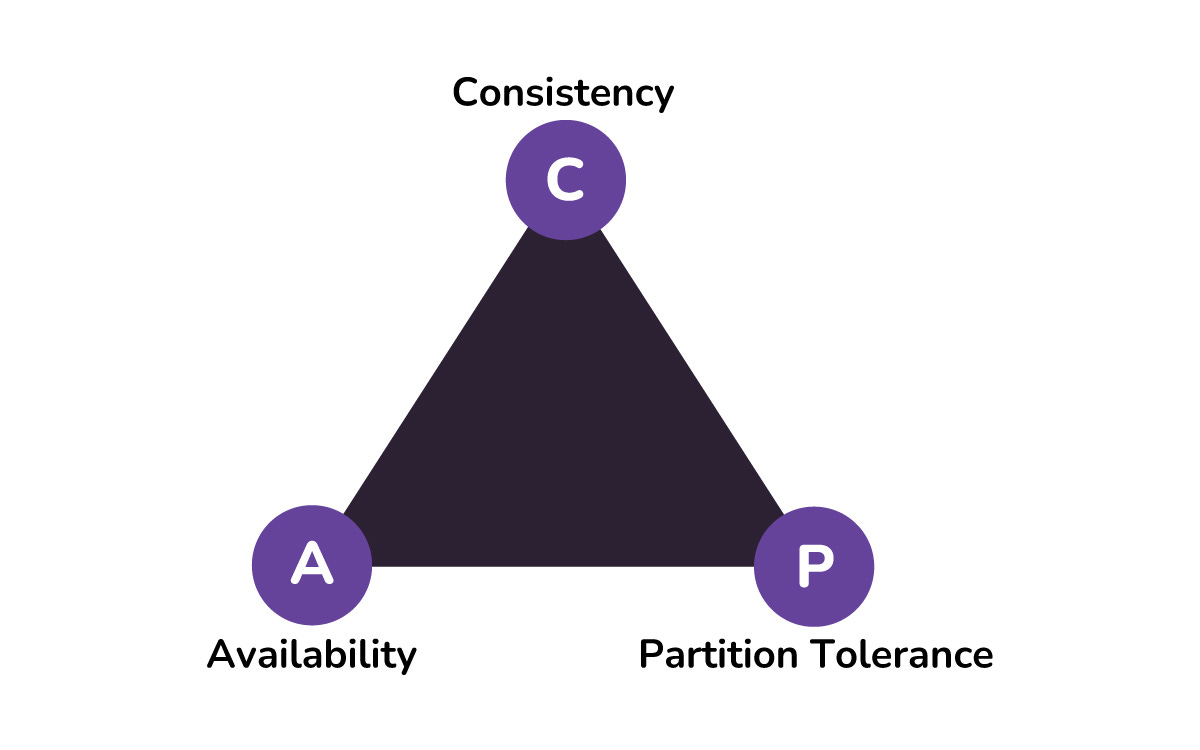

CAP Theorem

CAP Theorem says that in the presence of a network partition, a distributed system must choose between Consistency and Availability. Consistency means every user sees the same data at the same time.

Availability means the system always responds, even if the data might be slightly stale.

You cannot have perfect consistency and perfect availability when your network is broken, so you decide which one to sacrifice for your use case.

PACELC Theorem

PACELC extends CAP and says: if there is a Partition, choose Availability or Consistency; Else choose Latency or Consistency.

Even when the network is fine, you still trade off slow but consistent reads vs fast but eventually consistent reads. Systems that sync across regions often pay in latency to keep strong consistency.

It explains why some databases are fast but slightly stale, while others are slower but always accurate.

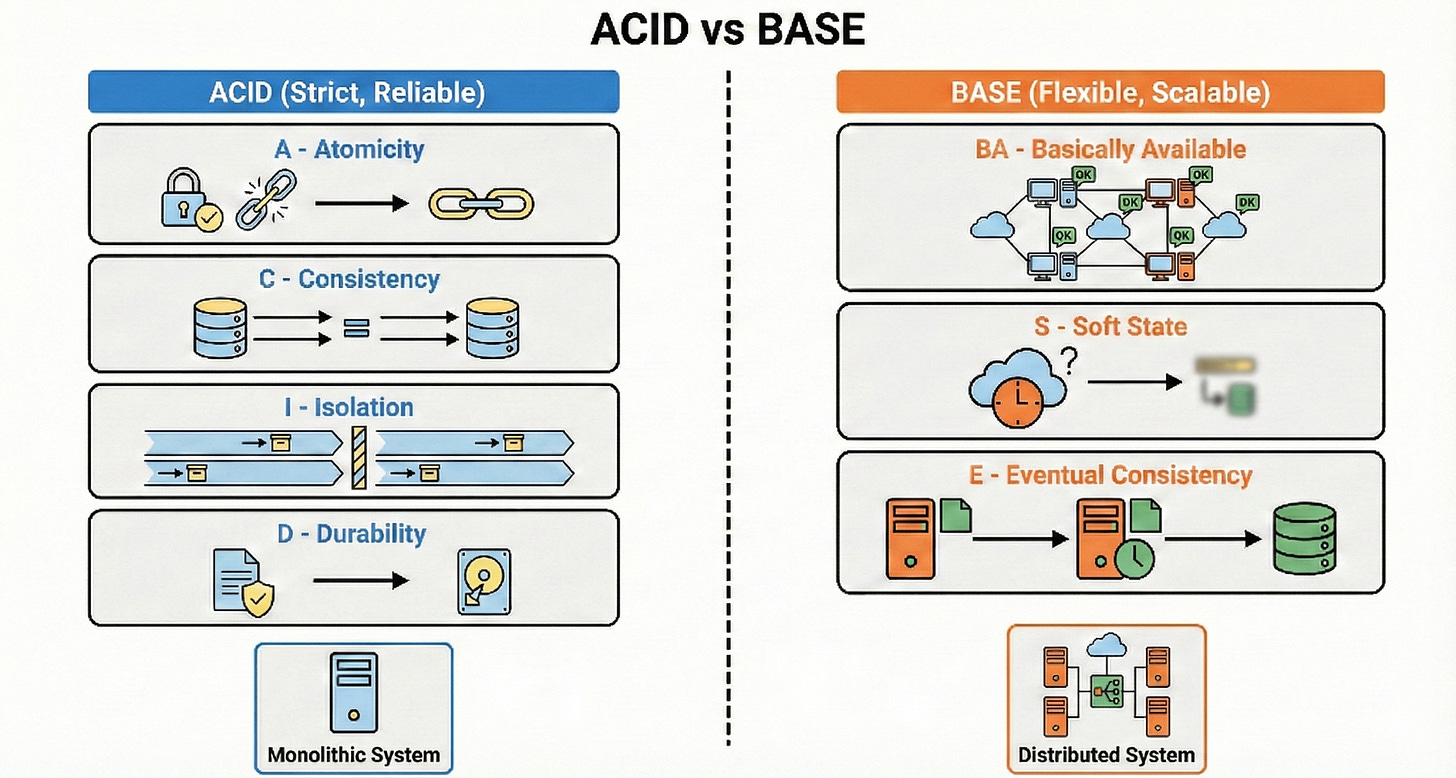

ACID vs BASE

ACID is about strict, reliable transactions: Atomicity, Consistency, Isolation, Durability. It suits financial systems, inventory, and anything where mistakes are very costly.

BASE stands for Basically Available, Soft state, Eventual consistency and is used in large distributed systems that need to stay up and respond quickly.

BASE systems might show temporary inconsistencies but fix themselves over time.

In practice, many architectures combine both, using ACID for core money flows and BASE for things like feeds and analytics.

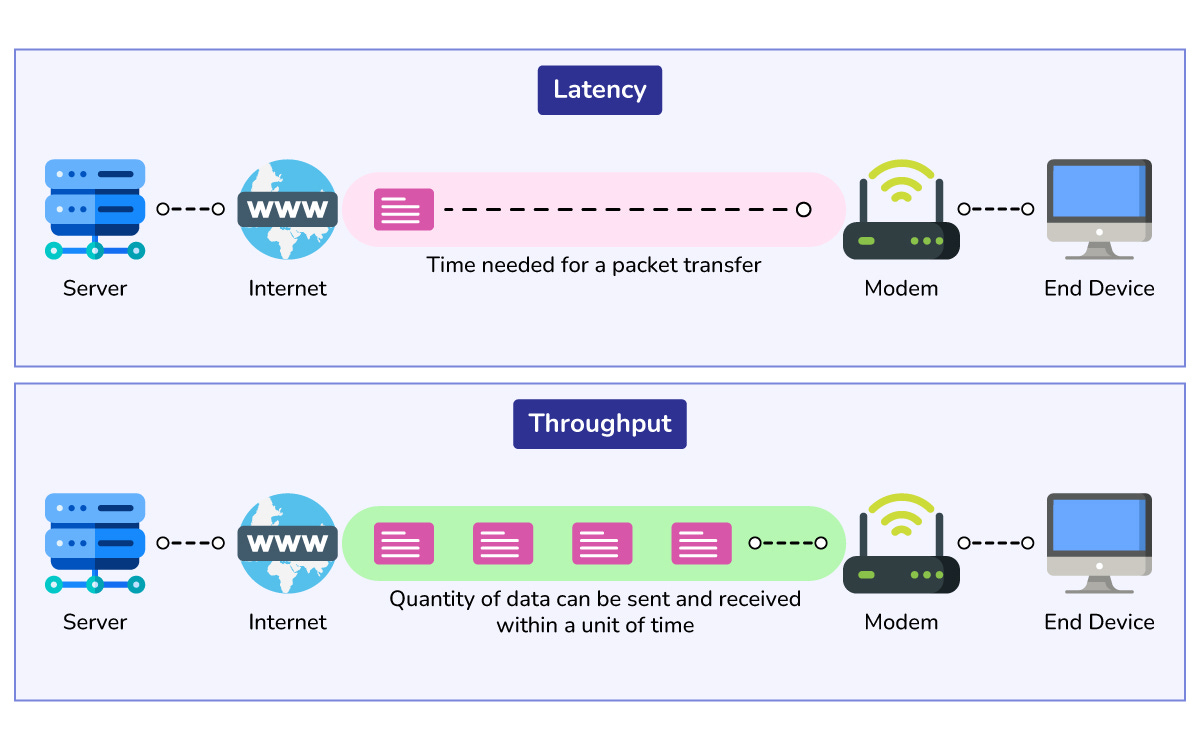

Throughput vs Latency

Throughput is how many requests your system can handle per second.

Latency is how long a single request takes from start to finish.

You can often increase throughput by doing more work in parallel, but that may increase latency if queues build up.

Think of a restaurant that takes many orders at once but makes customers wait longer. Good system design tries to balance both: enough throughput for peak load but low latency for a smooth user experience.

Amdahl’s Law

Amdahl’s Law says that the speedup from parallelization is limited by the part that cannot be parallelized.

If 20 percent of your system is always sequential, no amount of extra machines will fix that bottleneck.

Let me break it down.

If your request always has to hit a single master database, that master will cap your performance. This law reminds you to hunt for bottlenecks instead of just adding more servers.

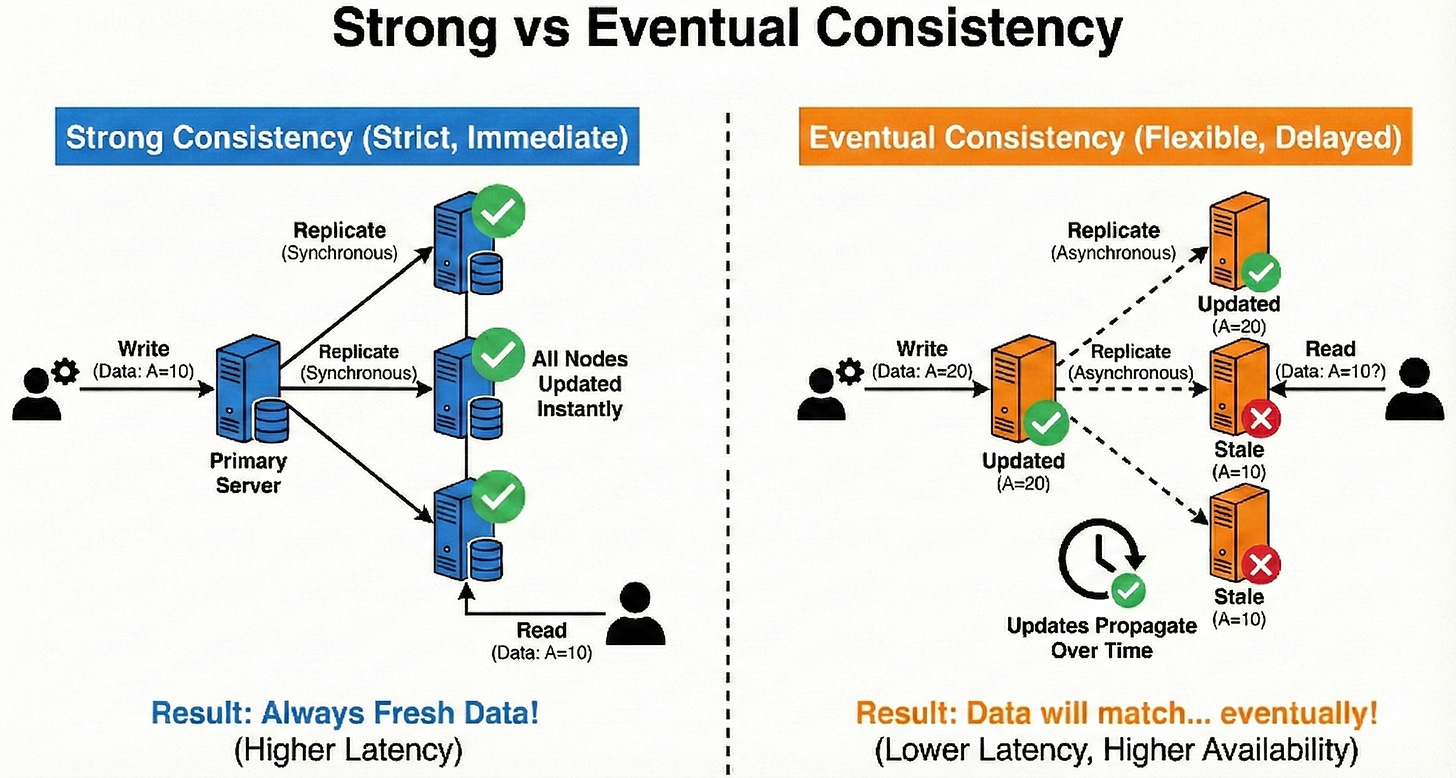

Strong vs Eventual Consistency

Strong consistency means all users see the same data immediately after a write.

Eventual consistency means updates spread over time and nodes may briefly disagree.

Strong consistency is easier to reason about but usually slower and less available under failures.

Eventual consistency is great for large-scale systems like timelines or counters where perfect freshness is not critical.

The key is to choose the model that matches the user experience you need.

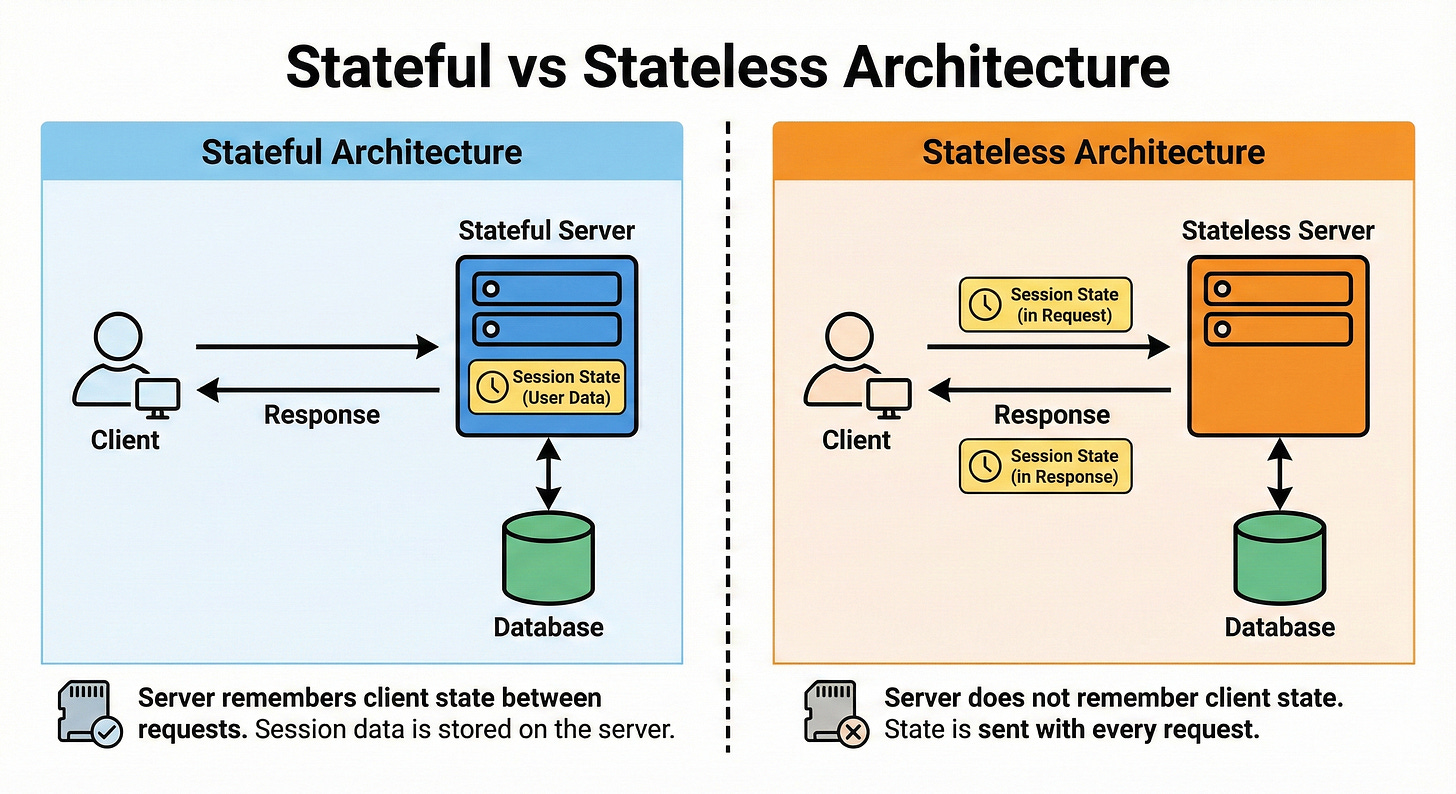

Stateful vs Stateless Architecture

A stateful service remembers user context between requests, often storing session data locally.

A stateless service treats every request as new, relying on external stores like caches or databases for any state.

Stateless services are easier to scale horizontally because any instance can handle any request.

Stateful systems can be simpler to code but harder to load balance and fail over.

In modern cloud systems, we try to push state into databases and keep services as stateless as possible.

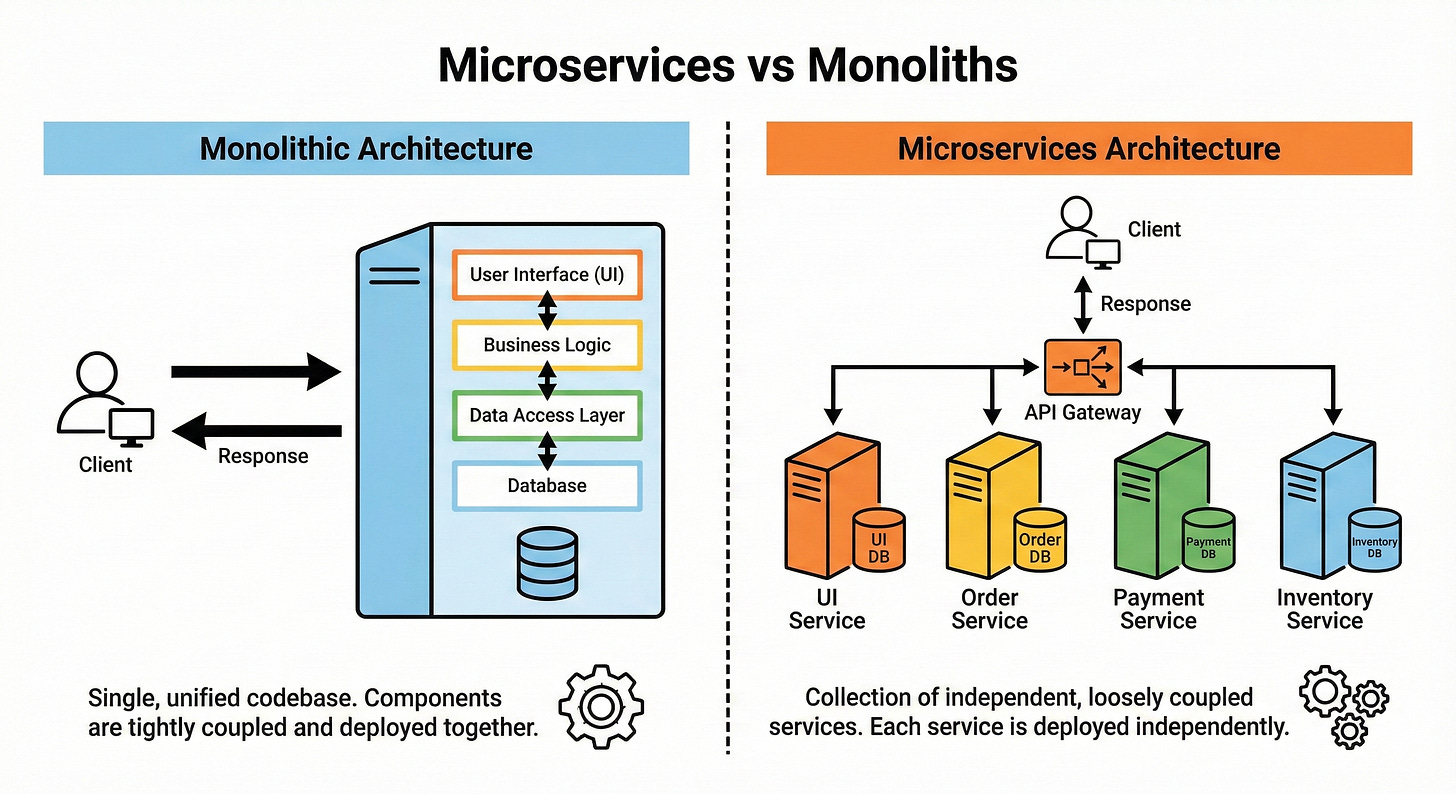

Microservices vs Monoliths

A monolith is a single application that contains many features in one deployable unit.

Microservices split features into separate services that communicate over the network.

Microservices help teams work independently and scale different parts separately, but introduce complexity around communication, debugging, and data consistency.

Monoliths are simpler to start with and often fine up to a certain scale. Here is the tricky part.

Many great systems start as monoliths and gradually evolve into microservices when the pain is real.

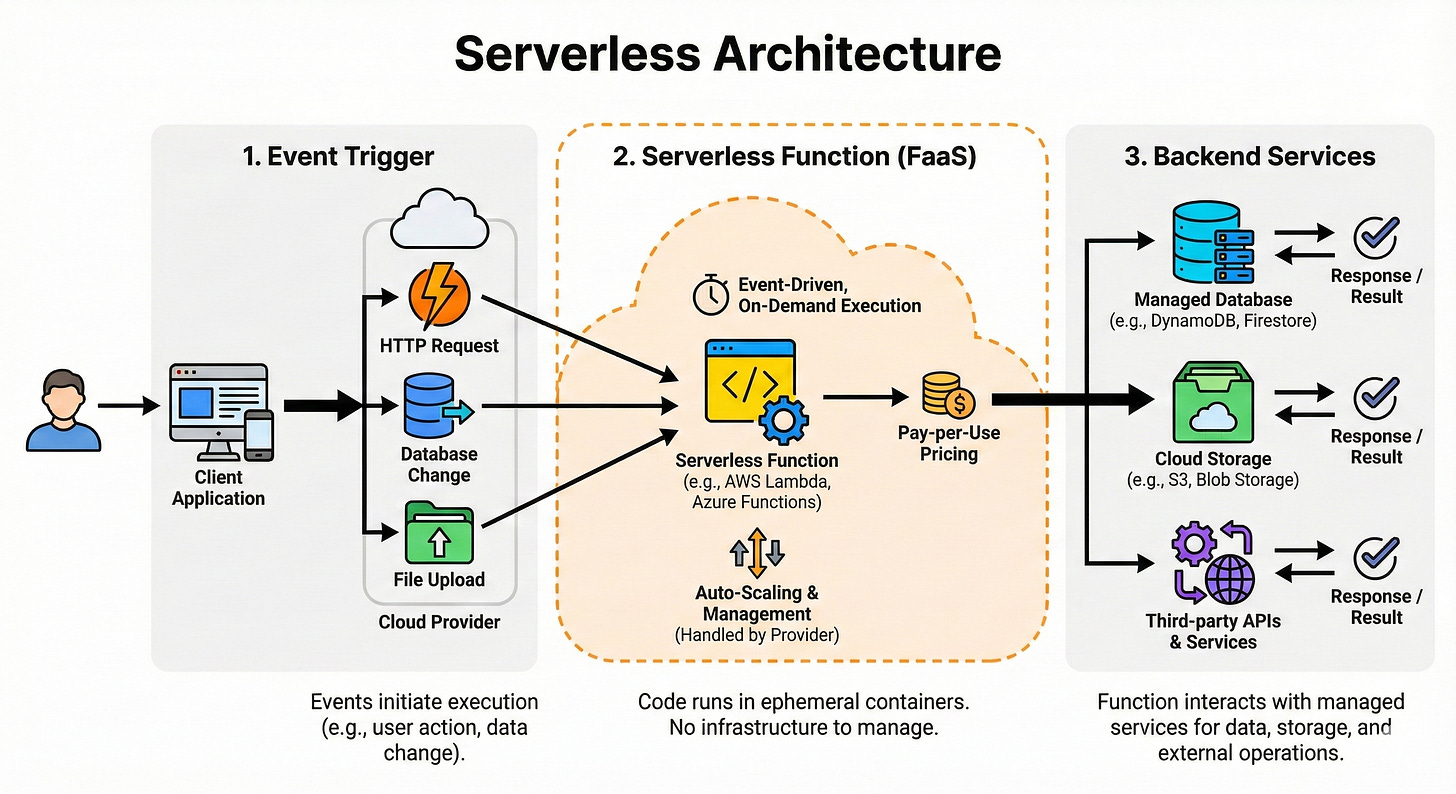

Serverless Architecture

Serverless lets you run small functions in the cloud without managing servers directly. You pay only when your code runs, and the platform handles scaling and infrastructure for you.

It is ideal for event-driven workloads such as webhooks, background jobs, or light APIs with spiky traffic.

The tradeoff is less control over long-running tasks, cold starts, and sometimes a higher cost at very high volumes.

Think of serverless as “functions as a service,” perfect for glue code and lightweight services.

II. Networking and Communication

Load Balancing

Load balancing spreads incoming traffic across multiple servers so no single server gets overloaded. It improves both reliability and performance, since a single server’s failure does not bring down the entire system.

Load balancers can be hardware devices or software services. They often support health checks so they stop sending traffic to unhealthy instances.

From an interview point of view, they are your first building block when scaling horizontally.

Load Balancing Algorithms

Common load balancing algorithms include Round Robin, Least Connections, and IP Hash.

Round Robin cycles through servers in order and is simple to implement.

Least Connections sends traffic to the server with the fewest active connections, which helps when requests vary in length.

IP Hash uses a hash of the client IP so the same user usually goes to the same server, which helps with simple session stickiness.

Picking the right algorithm affects fairness, resource usage, and user experience.

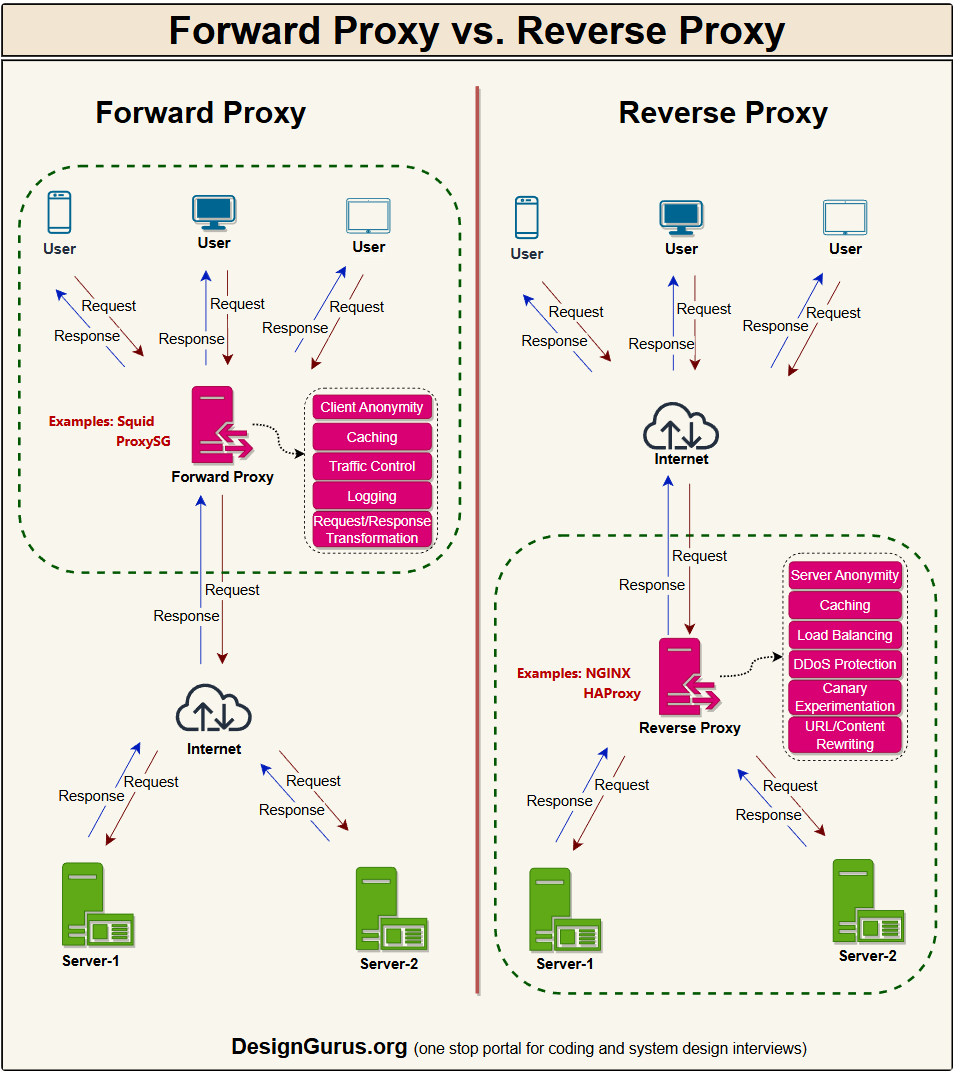

Reverse Proxy vs Forward Proxy

A reverse proxy sits in front of servers and represents them to clients. It hides the inner topology, can do TLS termination, caching, compression, and routing.

A forward proxy sits in front of clients and represents them to the outside world, often for security, caching, or content filtering.

Think of a reverse proxy as the reception desk of a company that hides all the internal rooms, and a forward proxy as a gateway your laptop must pass through to reach the internet.

Knowing the difference helps when you talk about API gateways and corporate proxies.

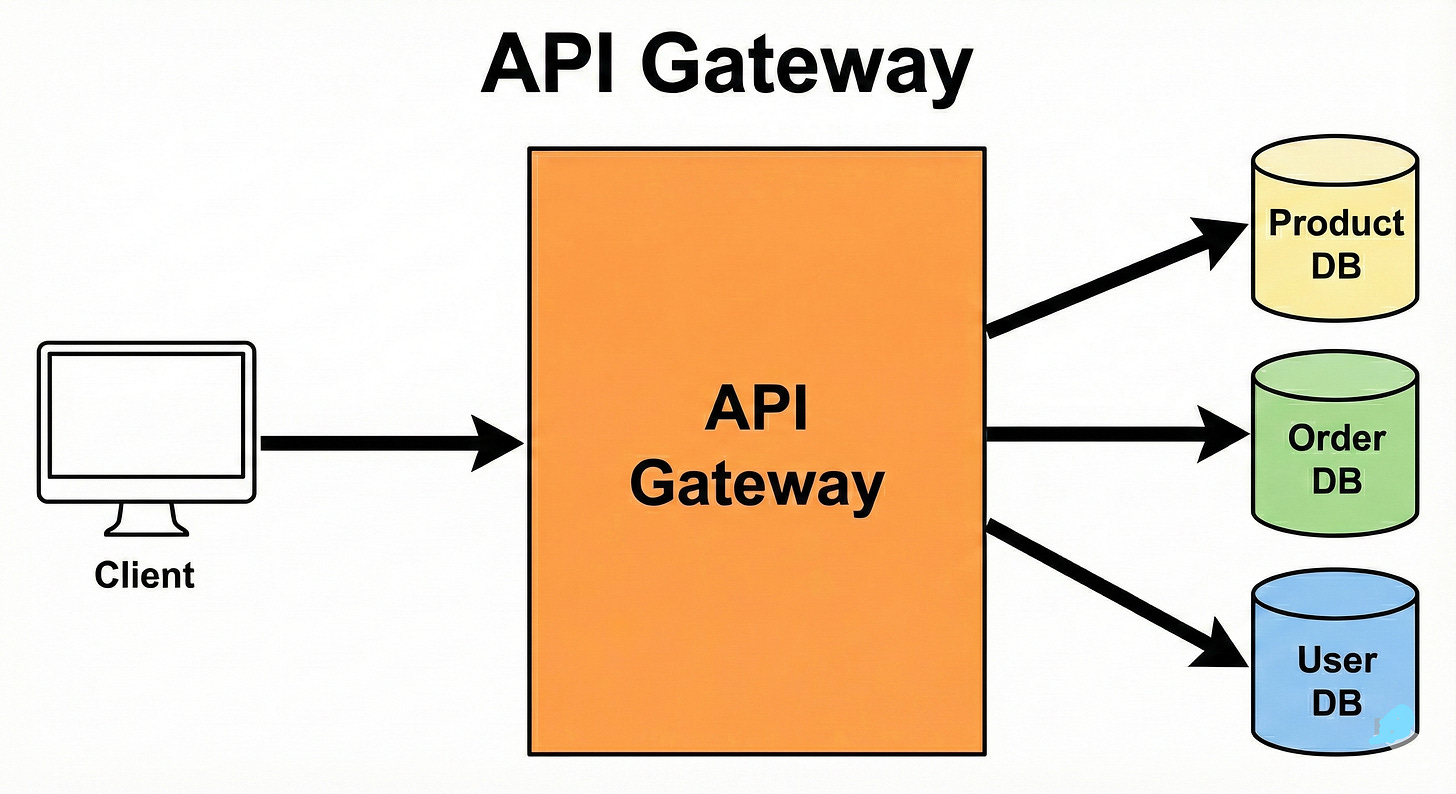

API Gateway

An API gateway is a special reverse proxy that acts as a single entry point for all API calls in a microservices system. It handles routing to the right service, rate limiting, authentication, logging, and sometimes response shaping.

This reduces complexity on the client side since clients only talk to one endpoint.

If you put too much logic in the gateway, it can become a bottleneck or a mini monolith of its own. Good designs keep it focused and thin.

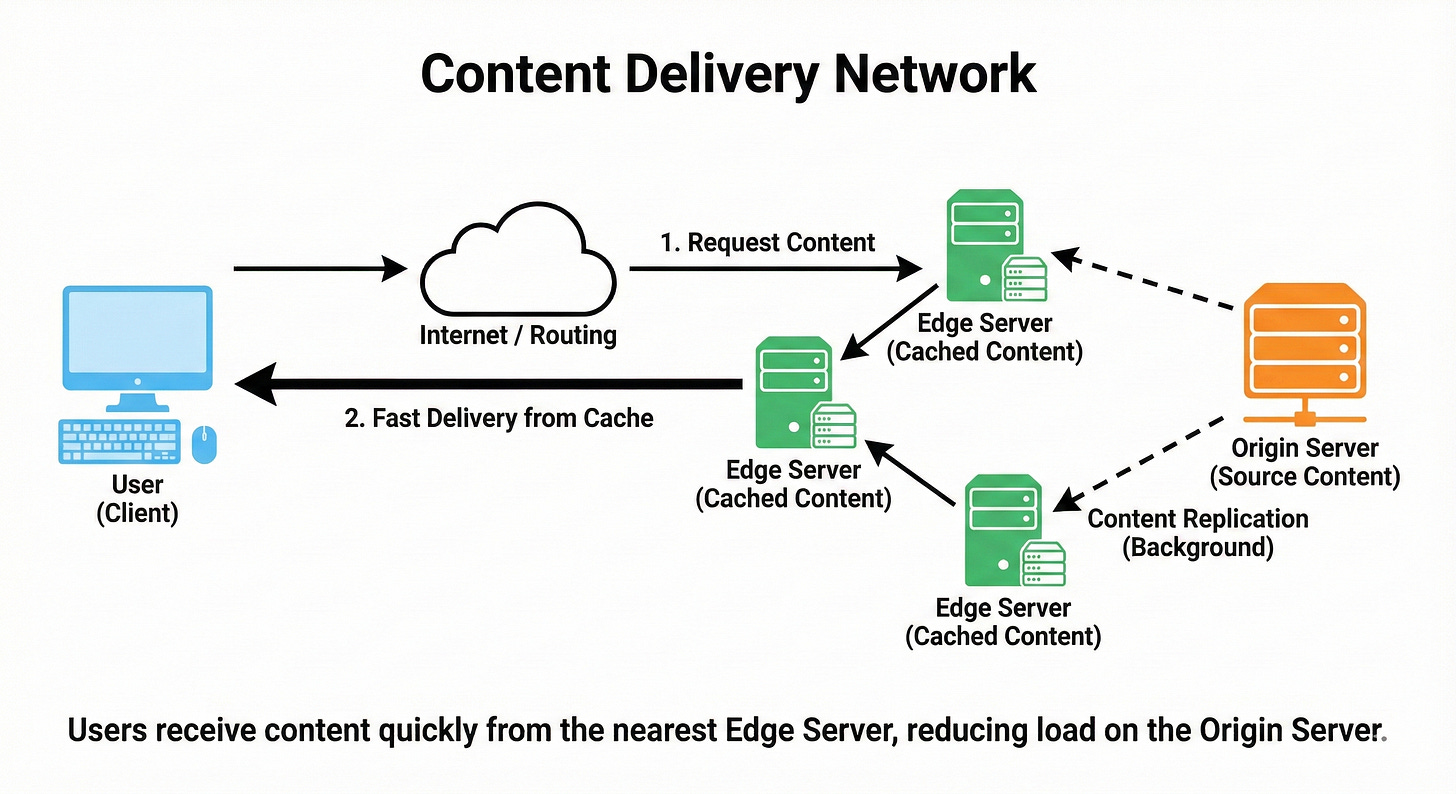

CDN (Content Delivery Network)

A CDN is a network of geographically distributed servers that cache static content like images, videos, and scripts closer to users.

When a user requests content, they are routed to the nearest CDN node, which greatly reduces latency. This also offloads traffic from your origin servers, improving scalability and resilience.

CDNs are essential for global applications and front-end performance.

Think of them as “local copies” of your website’s heavy files sprinkled around the world.

DNS (Domain Name System)

DNS maps human readable domain names to IP addresses.

When you type a website name, your device queries DNS to find the numeric address of the server.

has multiple layers of caching, so responses are fast after the first lookup. It can also be used to perform simple load balancing by returning different IPs for the same name.

Understanding DNS helps you reason about why name changes take time to propagate and why some outages are caused by misconfigured DNS.

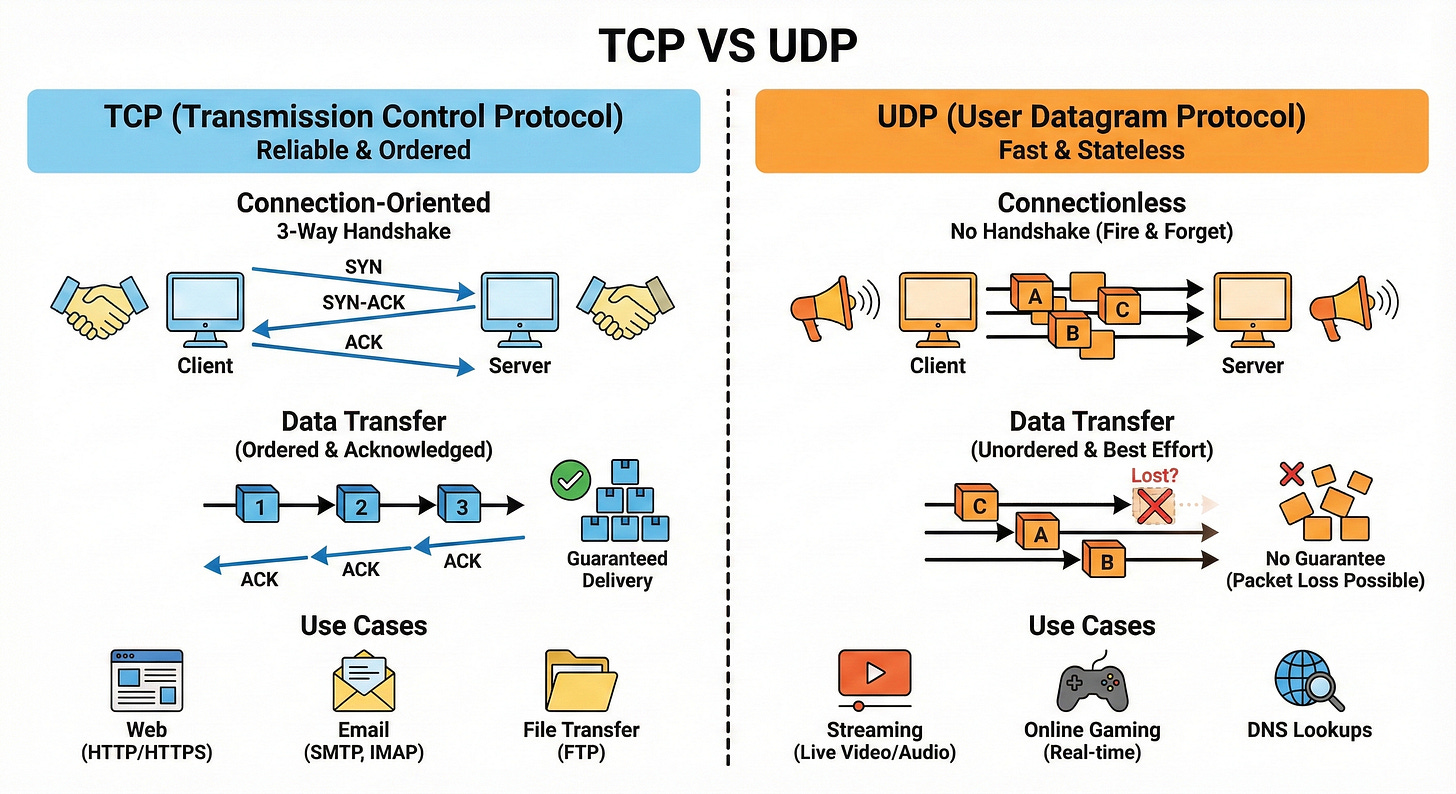

TCP vs UDP

TCP is a reliable, connection-oriented protocol. It guarantees ordered, error checked delivery by using acknowledgments and retries.

UDP is connectionless and does not guarantee delivery or order, which makes it much faster and lighter.

TCP suits APIs, web pages, and file transfers where accuracy matters.

UDP works well for real time applications like video calls or games where occasional packet loss is acceptable.

Think of TCP as registered mail and UDP as quick postcards.

HTTP/2 and HTTP/3 (QUIC)

HTTP/2 introduced multiplexing, which lets multiple requests share a single TCP connection, reducing overhead. It also brought features like header compression and server push.

HTTP/3 runs over QUIC, which is built on UDP and improves connection setup time and performance on unreliable networks. These versions mainly aim to reduce latency and better use modern network conditions.

For you as an engineer, the key idea is: fewer connection setups and better use of a single connection.

gRPC vs REST

REST typically uses HTTP with JSON and focuses on resources like

/usersor/orders. It is simple, human-readable, and widely used for public APIs.gRPC uses HTTP/2 and binary encoded messages (protobuf), which are smaller and faster over the wire. It also supports bidirectional streaming and strong typing.

In microservices, gRPC is often preferred for service-to-service calls, while REST is common for external clients.

Use REST when readability and compatibility matter, gRPC when performance and contracts matter.

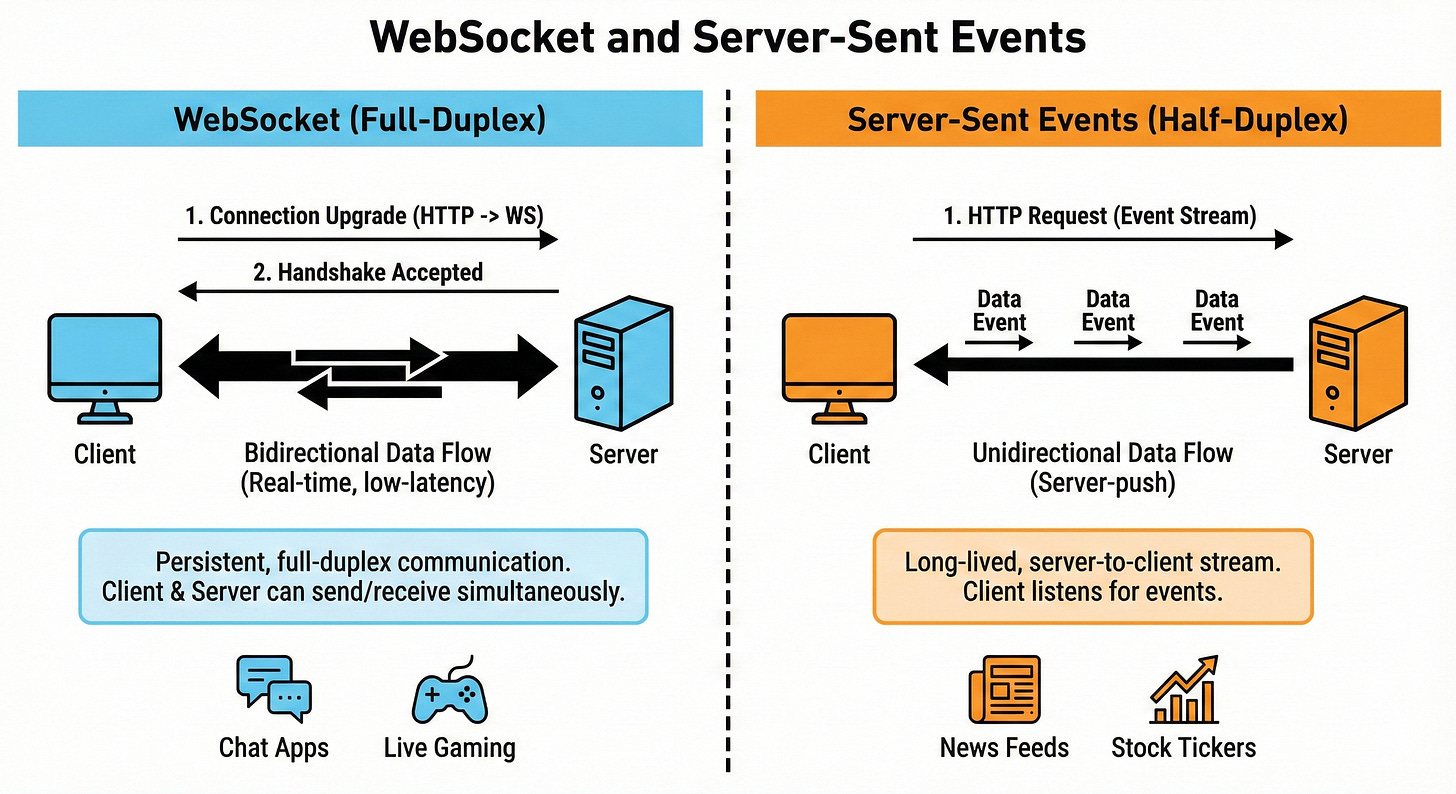

WebSocket and Server-Sent Events (SSE)

WebSockets create a full-duplex connection where client and server can send messages to each other at any time.

SSE allows the server to push events to the client over a one way channel using HTTP.

WebSockets are great for chats, multiplayer games, and live collaboration.

SSE is simpler and fits cases like live score updates or notifications where only the server needs to push updates.

Both solve real-time communication problems that plain HTTP cannot handle well.

Long Polling

Long polling is a technique where the client sends a request and the server holds it open until there is new data or a timeout.

When the response comes back, the client immediately opens another request. This simulates real time updates over plain HTTP without special protocols.

It is less efficient than WebSockets but easier to implement and works through most proxies and firewalls.

Think of it as asking “anything new?” and waiting quietly until there is an answer.

Gossip Protocol

A gossip protocol lets nodes in a distributed system share information by periodically talking to random peers.

Over time, information spreads like gossip in a social group until everyone has roughly the same view. It is used to share membership, health status, or configuration in a fault tolerant way.

The protocol is eventually consistent and does not rely on a central authority. This makes it ideal for large clusters where nodes frequently join and leave.

III. Database and Storage Internals

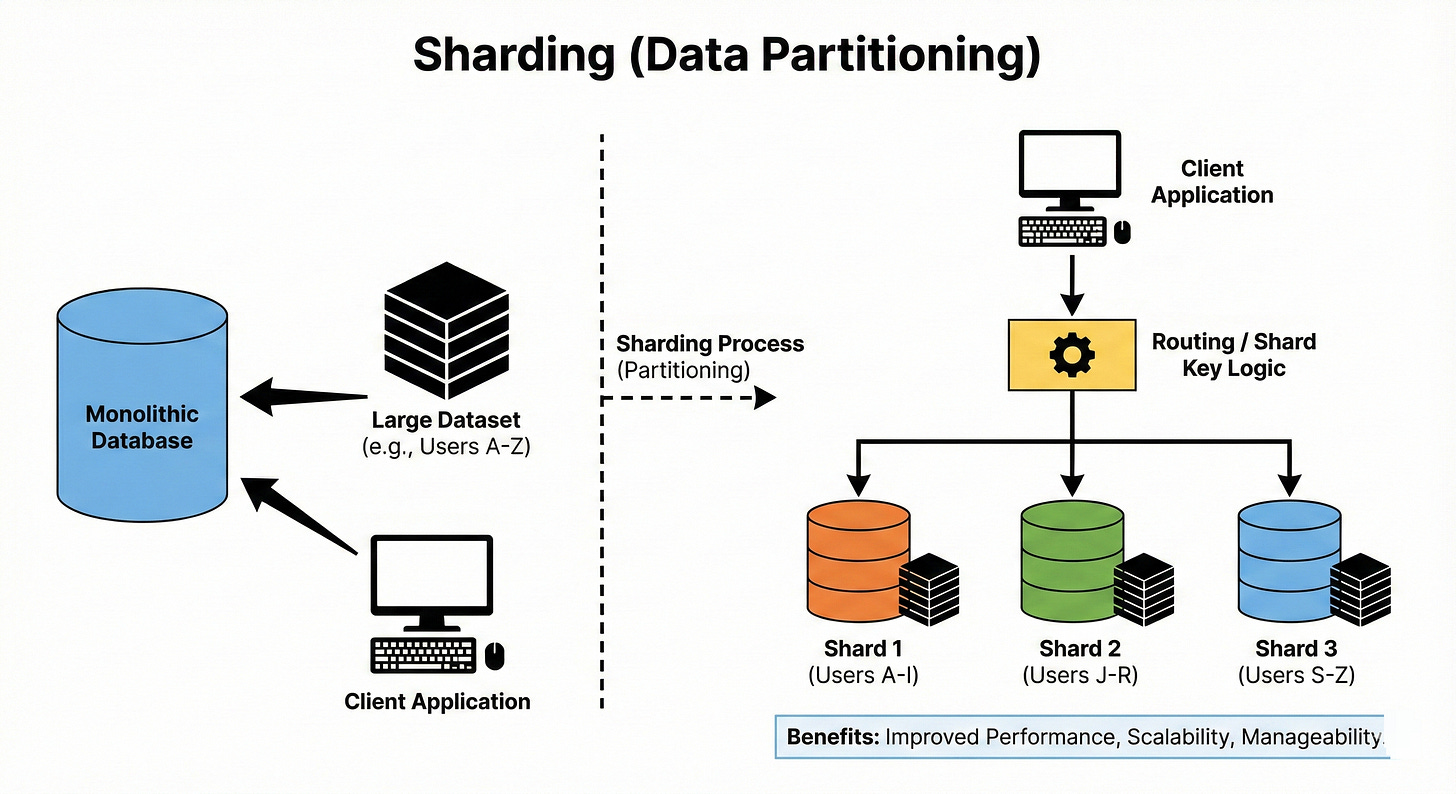

Sharding (Data Partitioning)

Sharding splits data across multiple machines, each holding a subset of the data. Common strategies include range-based sharding, hash-based sharding, and directory-based sharding.

The main goal is to scale storage and throughput by avoiding a single giant database node.

The tricky part is choosing a shard key that avoids hot spots where one shard gets most of the traffic. Once you shard, moving data between shards (resharding) becomes an important operational challenge.

Replication Patterns (Master Slave, Master Master)

Replication means keeping multiple copies of data on different nodes.

In master slave (or primary replica), one node handles writes and replicates changes to others that serve reads.

In master master (multi-primary), multiple nodes accept writes and reconcile conflicts.

Replication improves read performance and availability, but makes consistency harder, especially when writes go to multiple nodes.

In interviews, expect to talk about how replication lag affects reads and how failover works when a master dies.

Consistent Hashing

Consistent hashing is a technique to distribute keys across nodes in a way that minimizes data movement when nodes are added or removed.

Keys and nodes are placed on a logical ring, and each key belongs to the next node on the ring.

When a node joins or leaves, only a small portion of keys need to move. This property is very helpful in distributed caches and databases.

Think of it as a smooth mapping that does not get scrambled when the cluster size changes.

Database Indexing (B Trees, LSM Trees)

Indexes speed up queries by organizing data in a way that allows fast lookup.

B Trees are balanced trees that keep data sorted and let you find ranges efficiently, common in relational databases.

LSM Trees batch writes in memory and periodically flush them to disk, which makes writes very fast but reads more complex.

The tradeoff is write heavy vs read heavy workloads.

The key idea is that indexes are a separate structure that must be updated on every write, which is why too many indexes hurt insert performance.

Write Ahead Logging (WAL)

Write Ahead Logging records changes to a log before applying them to the main database.

If a crash happens in the middle of a transaction, the system can replay the log to restore a consistent state. WAL ensures durability and atomicity of transactions. It also allows techniques like replication from the log stream. Let me tell you why it is important.

Without WAL, a crash could leave your data in a half updated, corrupt state.

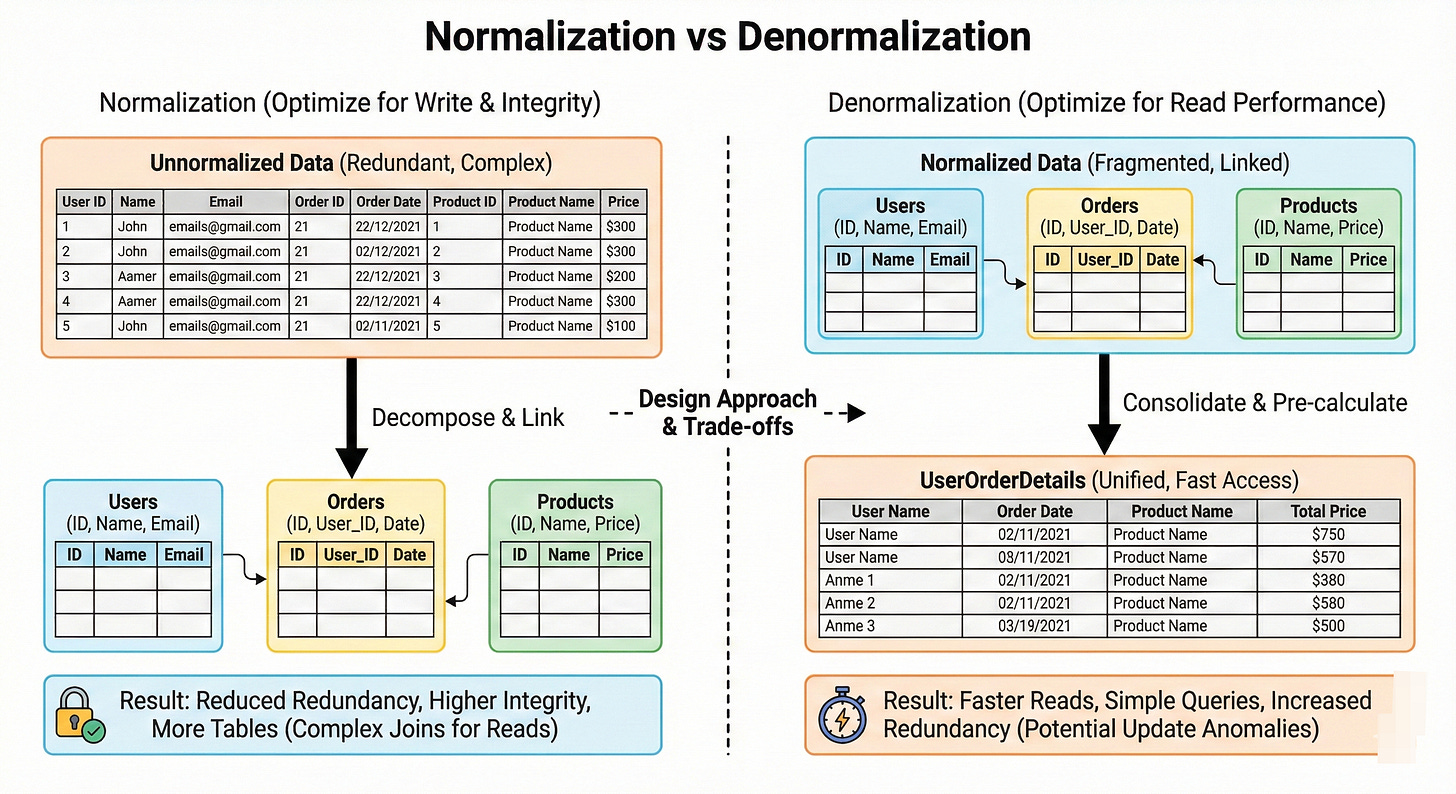

Normalization vs Denormalization

Normalization organizes data into tables that reduce redundancy and dependencies, following rules like first normal form, second normal form, and so on. This avoids anomalies on updates and inserts.

Denormalization intentionally duplicates data to speed up reads and reduce joins. In high scale systems, denormalization is common for read heavy paths, such as storing user names along with posts instead of joining every time.

The real skill is knowing where you can safely denormalize without breaking consistency.

Polyglot Persistence

Polyglot persistence means using multiple types of databases within the same system, each chosen for what it does best. You might use a relational database for transactions, a document store for logs, a key value store for caching, and a graph database for relationships.

Instead of forcing everything into one database, you pick the right tool for each job.

The tradeoff is more operational complexity and more knowledge required from the team.

Bloom Filters

A Bloom filter is a space efficient data structure that quickly answers “might this item be in the set?” with possible false positives but no false negatives. It uses multiple hash functions to set bits in a bit array when items are inserted.

To check membership, you test the same bits; if any bit is zero, the item is definitely not present.

Databases and caches use Bloom filters to avoid unnecessary disk lookups or cache misses.

Think of them as fast gatekeepers that say “definitely not” or “maybe.”

Vector Databases

Vector databases store and query vectors, which are numeric representations of data such as text, images, or audio. These vectors come from models like embeddings and allow similarity search, such as “find documents most similar to this one.”

Instead of exact equality comparisons, they use distance metrics like cosine similarity or Euclidean distance. This is essential for modern search, recommendation, and AI assistant systems.

In interviews, it is enough to know that vector databases support nearest neighbor search over high-dimensional data.

IV. Reliability and Fault Tolerance

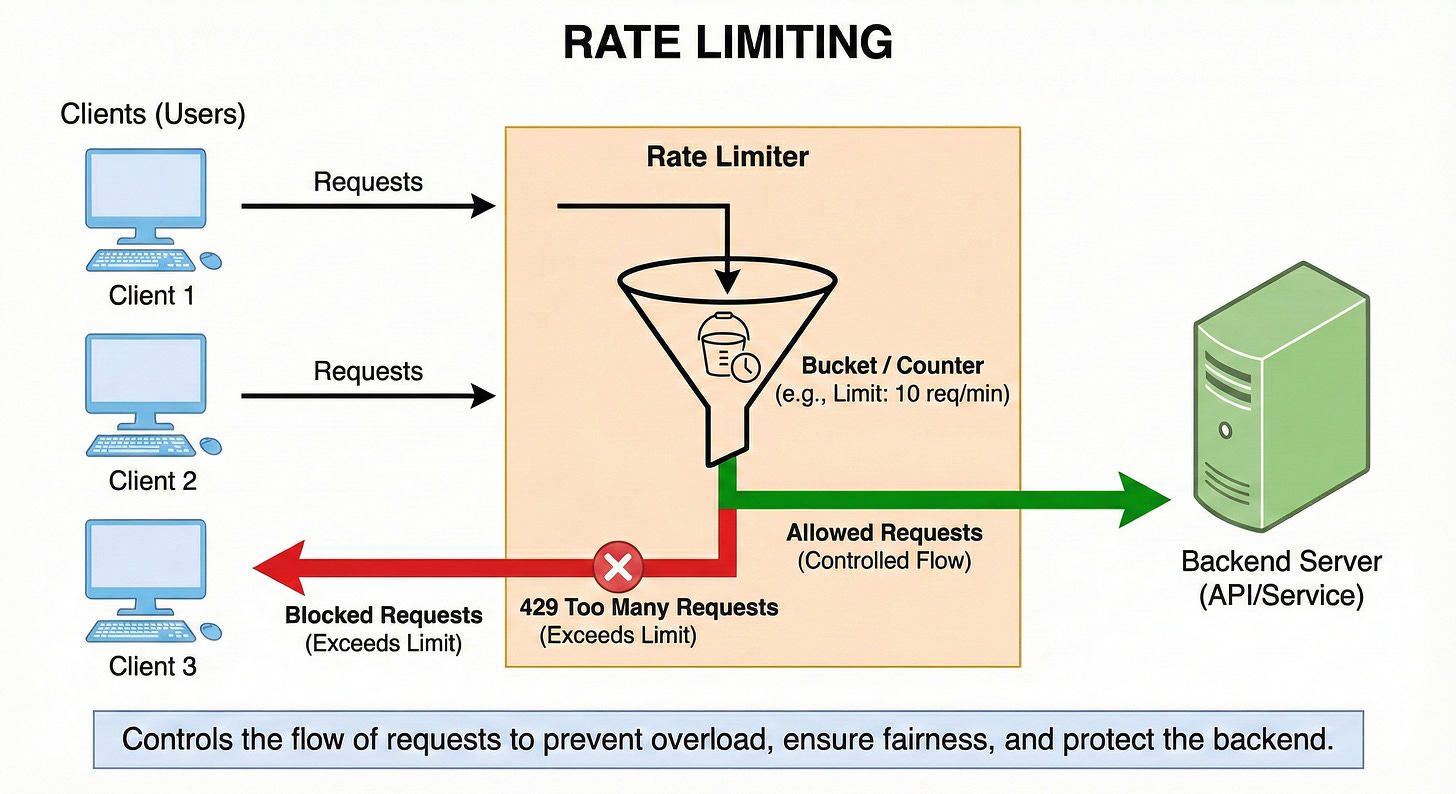

Rate Limiting

Rate limiting controls how many requests a user, IP, or API key can make in a given time window. It protects your system from abuse, accidental traffic spikes, and runaway loops.

Common strategies include fixed window, sliding window, and token bucket.

Rate limits are often enforced at the API gateway or load balancer.

Think of them as safety brakes that keep shared resources from being overwhelmed.

Circuit Breaker Pattern

A circuit breaker monitors calls to a remote service and “opens” if there are too many failures.

When open, it immediately fails new requests instead of trying the broken service again.

After a cooldown period, it allows a few trial calls to see if the service has recovered and closes if they succeed. This pattern prevents cascading failures where one slow service drags down the entire system.

Here is the tricky part. Circuit breakers must be tuned carefully so they do not open too aggressively or too late.

Bulkhead Pattern

The bulkhead pattern isolates parts of a system so a failure in one area does not sink everything. This can mean separate connection pools, thread pools, or even entire service clusters for different features.

If one bulkhead is flooded with traffic, others keep working.

The name comes from ship bulkheads that contain flooding in one compartment.

In design discussions, using bulkheads shows you are thinking about fault isolation and blast radius.

Retry Patterns and Exponential Backoff

Retries help recover from transient errors like network timeouts or temporary overload.

Exponential backoff means each retry waits longer than the previous one, such as 1 second, 2 seconds, 4 seconds, and so on. This prevents your client from hammering a service that is already struggling.

Good retry policies also use jitter (small randomness) to avoid thundering herds.

Let me break it down.

Retries without backoff can make outages worse instead of helping.

Idempotency

An operation is idempotent if performing it multiple times has the same effect as performing it once.

For example, “set user status to active” is idempotent, while “increment account balance by 10” is not.

Idempotency is critical when systems use retries, because the same request may be sent more than once.

APIs often require idempotency keys on operations like payments to avoid double charging.

In interviews, always mention idempotency when you talk about at least once delivery or retries.

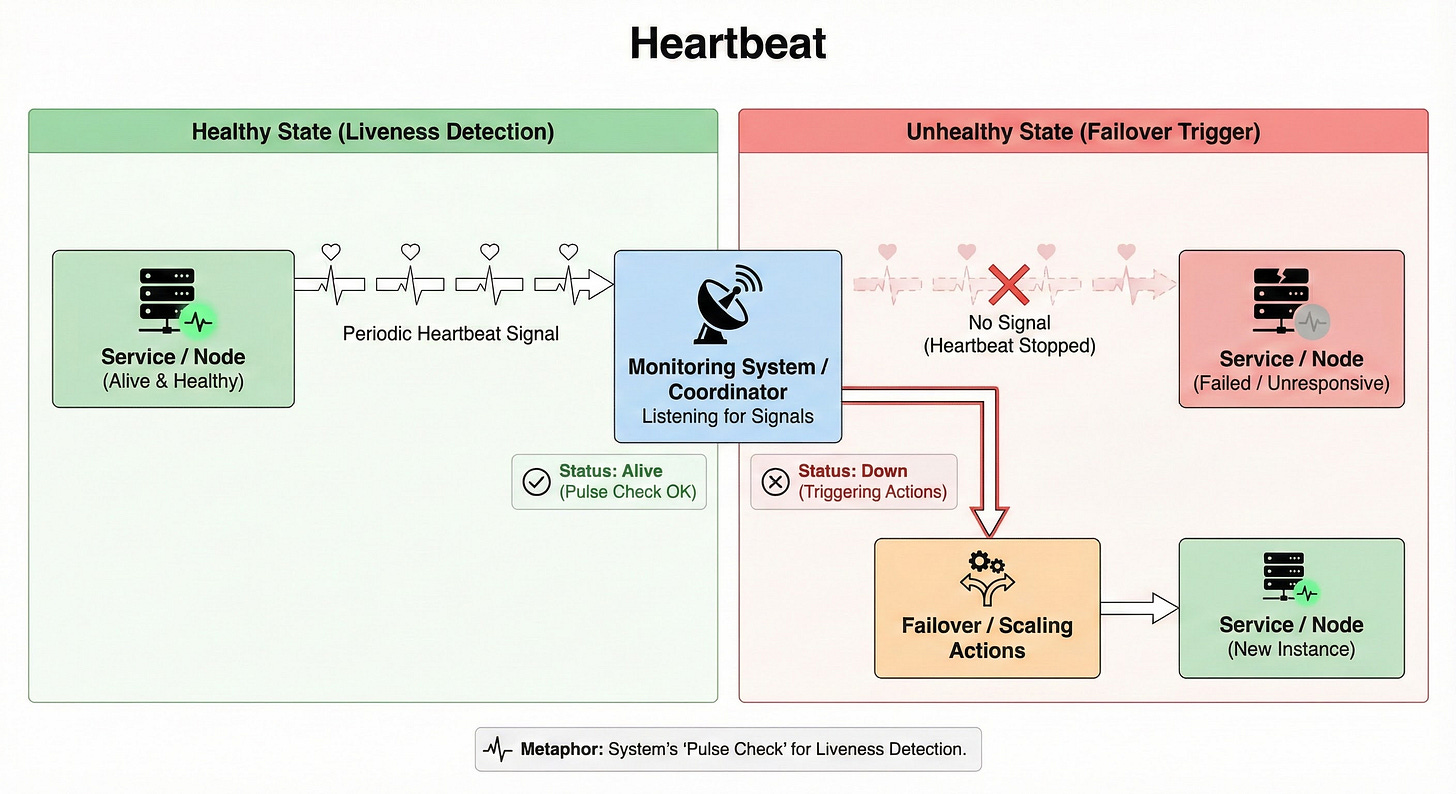

Heartbeat

A heartbeat is a periodic signal sent by a service or node to indicate that it is alive and healthy.

Monitoring systems or coordinators listen for heartbeats.

If they stop receiving them, they mark the node as down and trigger failover or scaling actions.

Heartbeats are simple but powerful tools for liveness detection. Think of them as the system’s “pulse checks.”

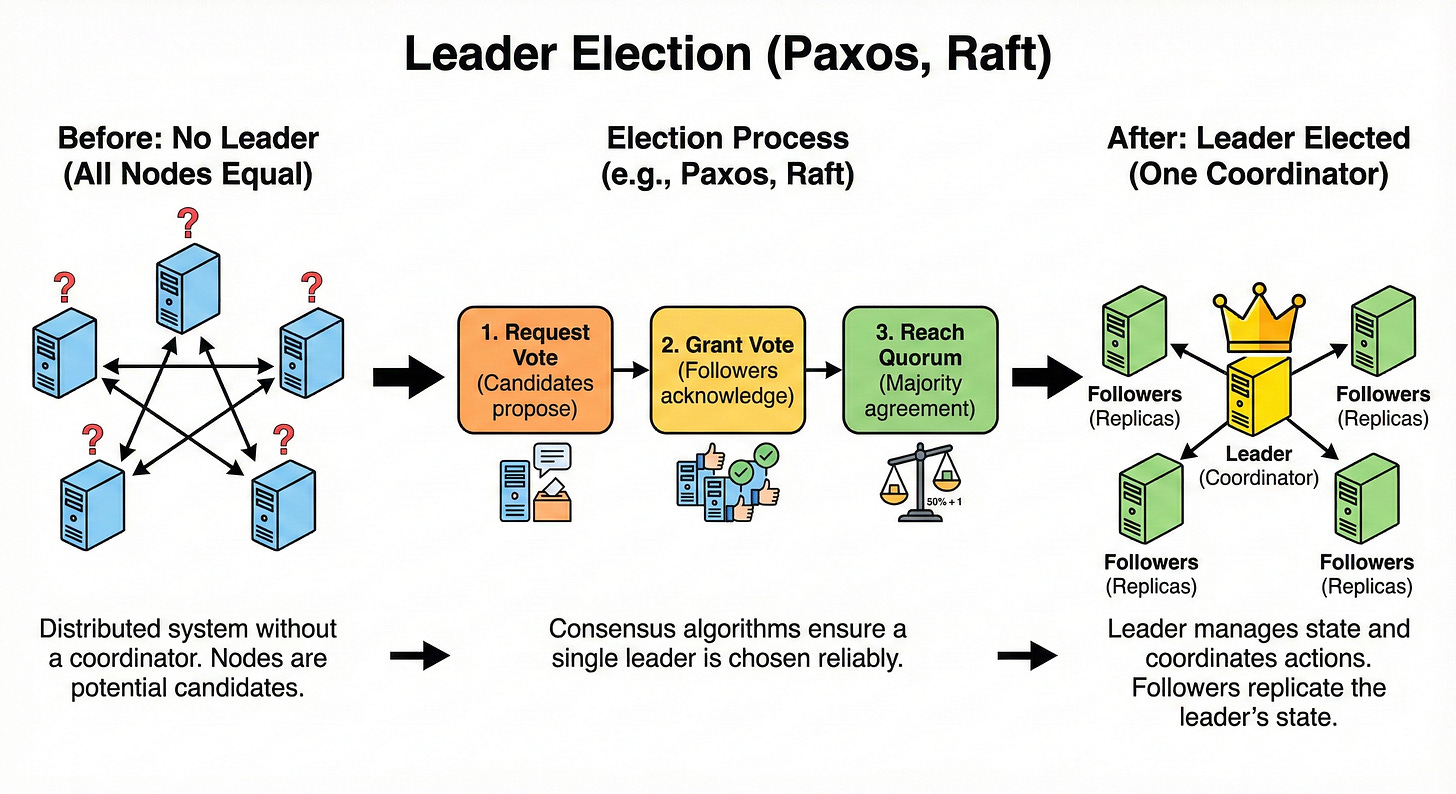

Leader Election (Paxos, Raft)

Leader election is the process of choosing a single node to act as a coordinator among many.

Algorithms like Paxos and Raft ensure that only one leader is chosen and that all nodes eventually agree on who that leader is.

The leader handles tasks like assigning work, managing metadata, or ordering writes. If the leader fails, a new one is elected automatically.

You do not need to memorize the math for interviews, but you should know that consensus algorithms power many critical systems like metadata stores and distributed logs.

Distributed Transactions (SAGA Pattern)

A distributed transaction spans multiple services or databases.

The SAGA pattern models such a transaction as a sequence of local steps with compensating actions for rollbacks.

Instead of locking everything like a single ACID transaction, each service performs its part and publishes an event. If something fails, compensating steps attempt to undo previous changes. This fits naturally with microservices and eventual consistency.

The tradeoff is more complex logic and the possibility of partial failures that must be handled gracefully.

Two Phase Commit (2PC)

Two Phase Commit is a protocol that tries to provide atomic transactions across multiple nodes.

In the first phase, the coordinator asks all participants if they can commit.

In the second phase, if everyone agrees, it tells them to commit; otherwise, it tells them to roll back.

2PC provides strong guarantees but can block if the coordinator fails, and it is expensive at scale due to locking.

In modern cloud systems, 2PC is often avoided for high throughput paths and replaced by patterns like SAGA.

V. Caching and Messaging

Caching

Caching stores frequently accessed data in a fast storage layer, usually memory, to reduce latency and backend load.

Common cache layers include in process caches, external key value stores, and CDNs. Caching is especially effective for read heavy workloads and expensive computations.

Here is the tricky part. Stale data and invalidation make caching harder than it first appears.

As the saying goes, cache invalidation is one of the hard problems in computer science.

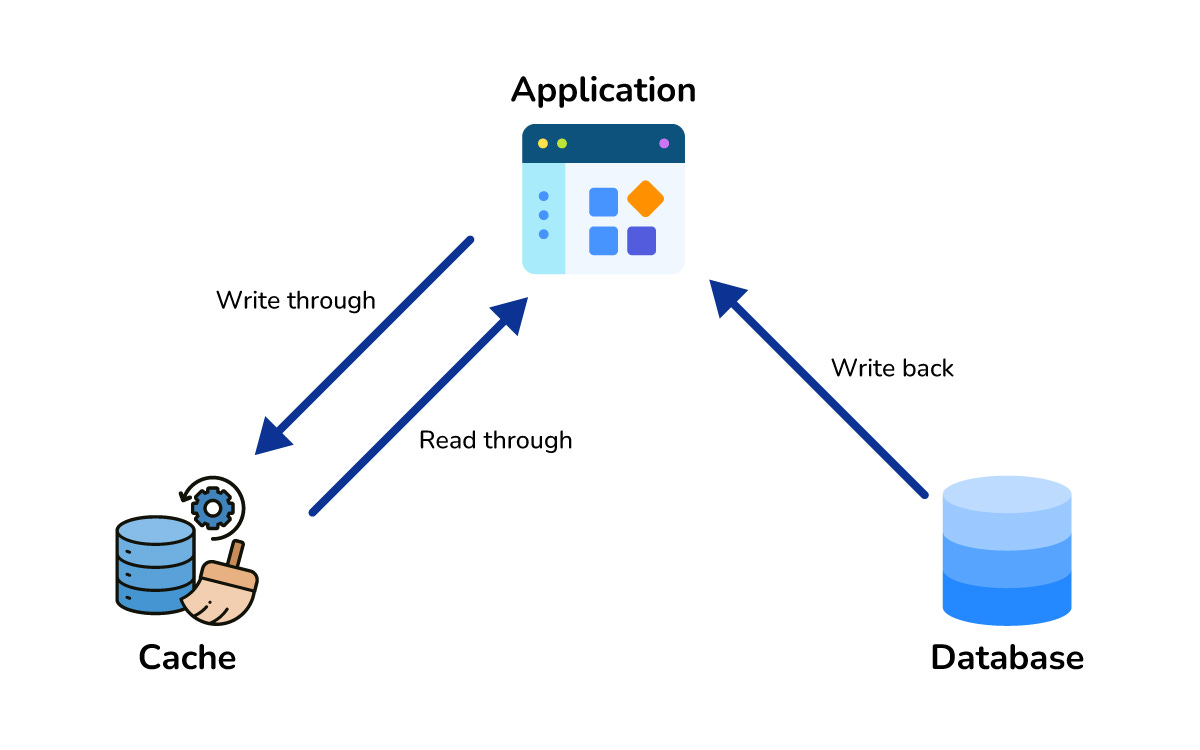

Caching Strategies (Cache Aside, Write Through, etc.)

Cache aside means the application reads from the cache, and on a miss, loads from the database and writes to the cache.

Write through writes to the cache and database at the same time, ensuring cache and source are always in sync.

Write back writes to the cache first and flushes to the database later, which is fast but risky if the cache fails.

Each strategy balances freshness, complexity, and performance differently.

Interviewers love when you mention which strategy you would pick for a given scenario.

Cache Eviction Policies (LRU, LFU)

Cache eviction policies decide which items to remove when the cache is full.

LRU (Least Recently Used) evicts items that have not been accessed recently, assuming recent items are more likely to be used again.

LFU (Least Frequently Used) evicts items that are rarely accessed, focusing on long term popularity.

Some systems use random, FIFO, or advanced algorithms.

The key idea is that cache space is limited, so you want to keep the most valuable items in memory.

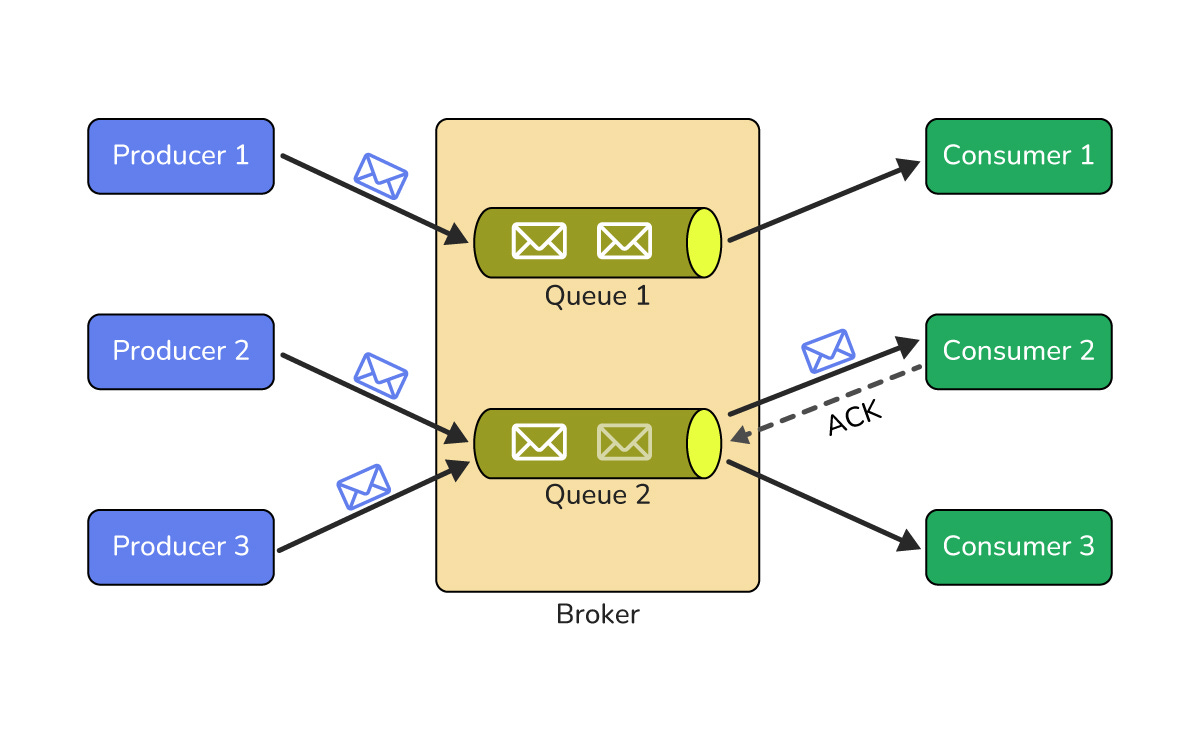

Message Queues (Point to Point)

A message queue allows one component to send messages to another without needing both to be online at the same time.

In a point to point model, messages in a queue are consumed by one receiver and then removed. This decouples sender and receiver so they can scale and fail independently.

Queues are great for background jobs, email sending, and processing heavy tasks asynchronously.

Think of them as a todo list shared between services.

Pub Sub (Publish Subscribe)

In pub sub, publishers send messages to topics, not directly to consumers.

Subscribers listen to topics they care about and receive copies of relevant messages. This enables broadcast style communication and loose coupling between producers and consumers.

Multiple services can react to the same event in different ways, such as logging, analytics, and notifications.

In interviews, pub sub often appears in event driven designs like activity feeds or event sourcing.

Dead Letter Queues

A dead letter queue stores messages that could not be processed successfully after several attempts.

Instead of retrying forever and blocking the main queue, these messages are moved aside.

Engineers can inspect the dead letter queue to debug issues, fix data, or replay messages later. This pattern improves resiliency and keeps your system from getting stuck on “poison messages.”

Think of it as a holding area for problematic jobs.

VI. Observability and Security

Distributed Tracing

Distributed tracing tracks a single request as it flows through multiple services. Each service adds a trace ID and span information so you can reconstruct the full path of a request. This is extremely helpful when debugging slow responses or failures in microservice architectures.

Without tracing, you just see errors in isolation. With it, you see the whole story across services, queues, and databases.

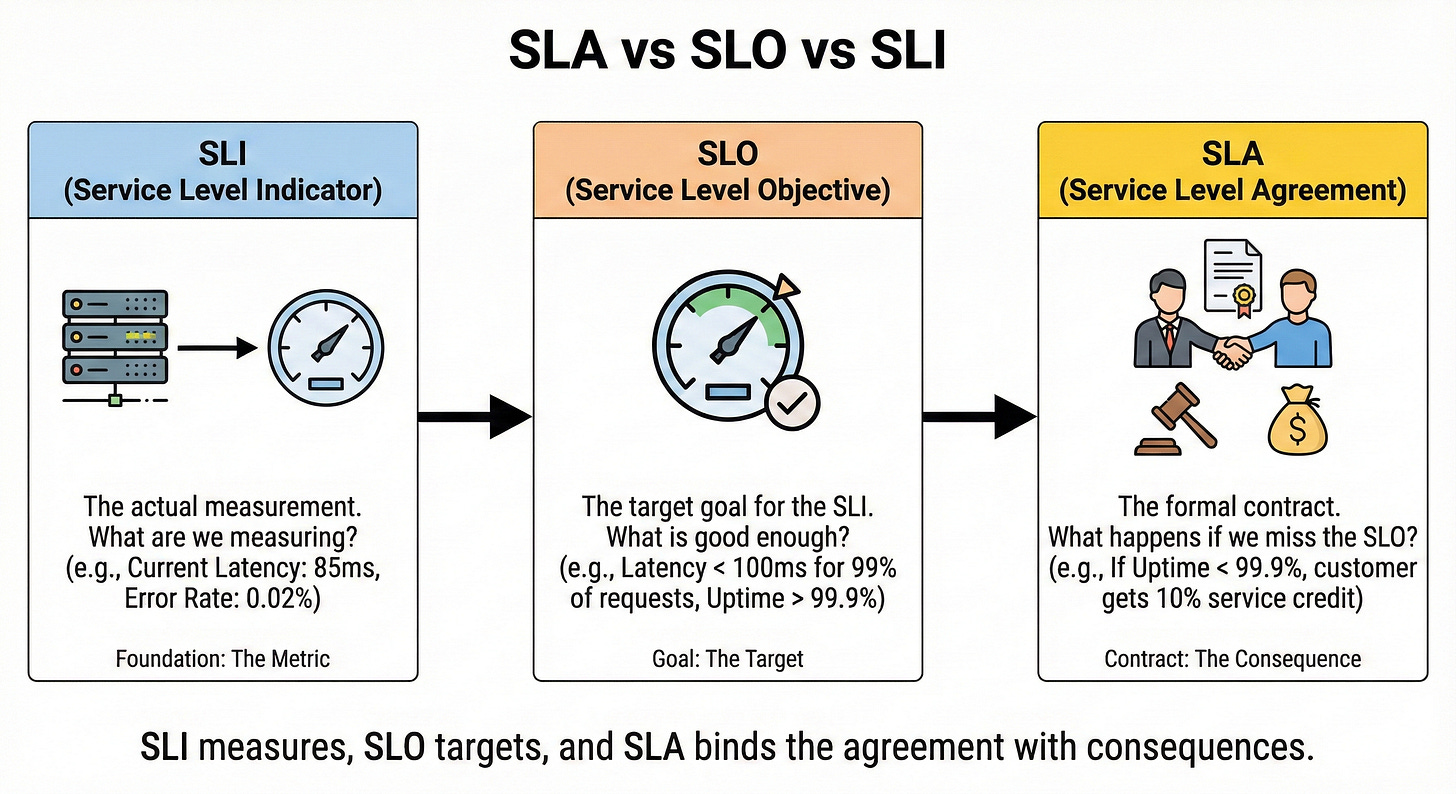

SLA vs SLO vs SLI

An SLA (Service Level Agreement) is an external promise to customers, such as “99.9 percent uptime per month.”

An SLO (Service Level Objective) is an internal target that engineers aim to meet, usually stricter than the SLA. An SLI (Service Level Indicator) is the actual measured metric, like real uptimes or request success rates.

Think of SLA as the contract, SLO as the goal, and SLI as the scoreboard.

In interviews, using these terms correctly shows maturity in thinking about reliability.

OAuth 2.0 and OIDC

OAuth 2.0 is a framework for delegated authorization. It lets users grant an application limited access to their resources without sharing passwords.

OIDC (OpenID Connect) builds on OAuth 2.0 to add authentication, letting clients verify who the user is and get user identity information. This is the basis of many “Login with X” flows.

The key idea is that an authorization server issues tokens that clients and APIs can trust.

TLS/SSL Handshake

TLS/SSL secures communication between client and server by encrypting data in transit.

During the handshake, the client and server agree on encryption algorithms, exchange keys securely, and verify certificates.

Once the handshake completes, all subsequent data is encrypted and safe from eavesdropping. This is what puts the little lock icon in your browser.

Without TLS, anyone on the network could read or modify sensitive traffic.

Zero Trust Security

Zero Trust is a security model that says: “Never trust, always verify.” It assumes that threats can exist both outside and inside the network.

Every request must be authenticated, authorized, and encrypted, even if it comes from within your data center or VPC. Access is granted based on identity, device posture, and context, not just on being “inside the firewall.”

In modern architectures, Zero Trust is becoming the default approach to secure system design.

Reference

Key Takeaways

System design is mostly about understanding trade-offs: consistency vs. availability, latency vs. throughput, simplicity vs. flexibility.

Scaling is not just “add more servers.” You must think about load balancing, sharding, replication, and bottlenecks.

Reliability patterns like rate limiting, circuit breakers, retries, and bulkheads exist because failures are normal in distributed systems.

Caching, queues, and pub-sub are your best friends for performance and decoupling, but they introduce new challenges around consistency and ordering.

Observability and security concepts such as tracing, SLIs, OAuth, TLS, and Zero Trust are essential for systems that are not just fast but also safe and debuggable.