16 API Gateway Concepts Every Software Engineer Should Know

Master API Gateways with this detailed breakdown of sixteen essential concepts explained simply with practical examples for developers and interview candidates.

When you break a system into microservices, things quickly become complicated.

Clients must talk to many services, manage different URLs, handle authentication for each one, deal with failures, and cope with version changes.

An API Gateway solves all of this by acting as the single front door into your system.

It handles routing, security, performance optimizations, and reliability patterns that keep the platform stable even under massive load.

Below are the sixteen most important gateway concepts every engineer must understand, each explained in depth with clear examples.

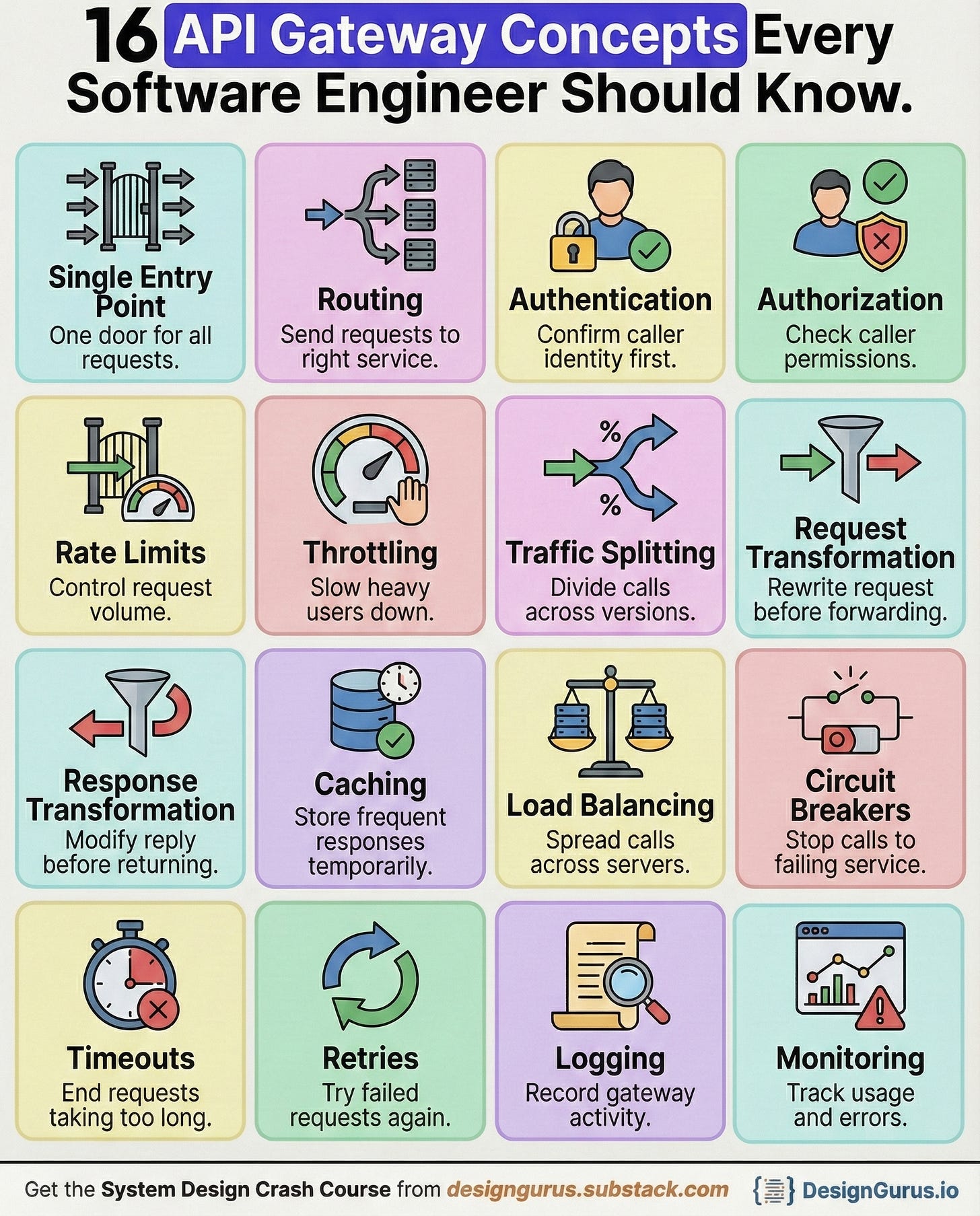

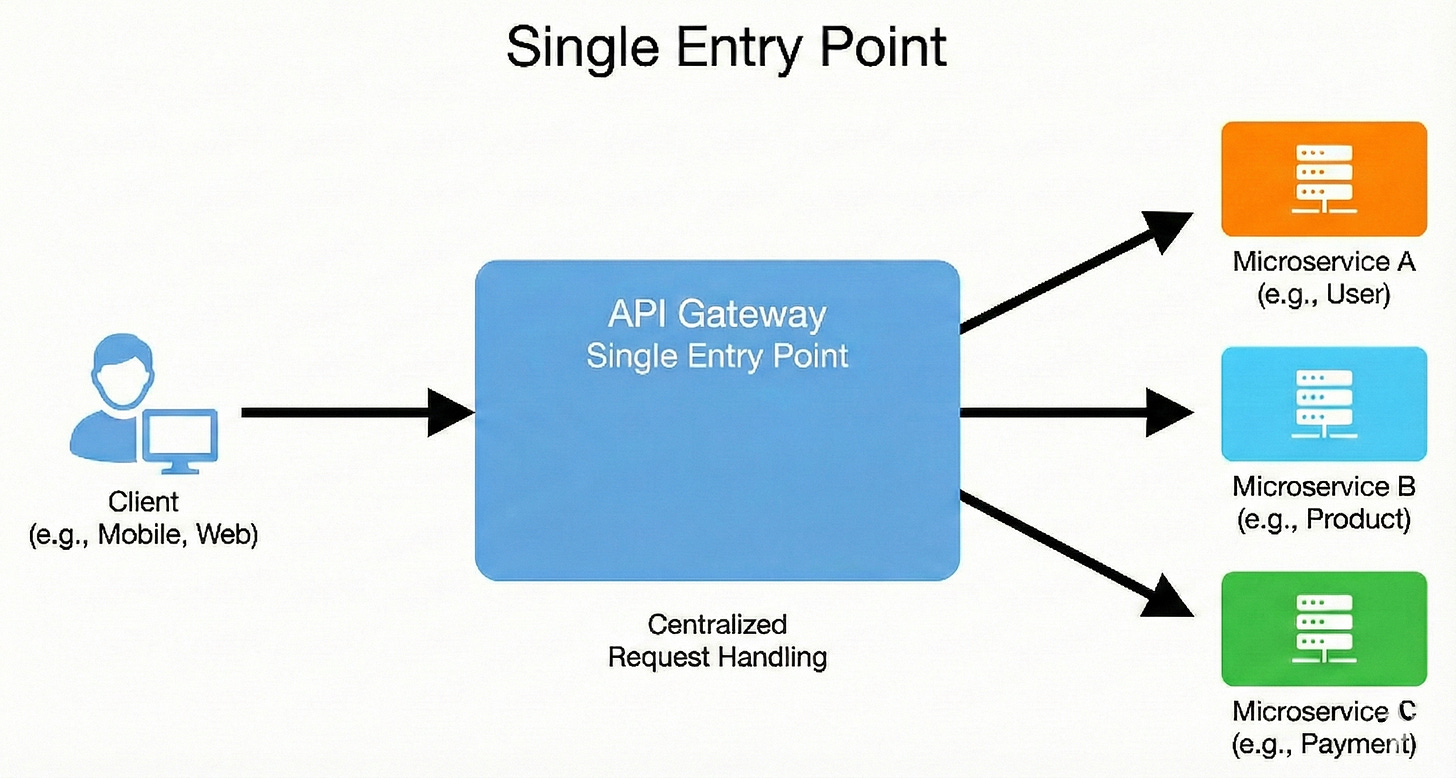

1. Single Entry Point

The API Gateway provides a single, unified URL or endpoint through which all external clients must interact with the application.

Instead of clients needing to know the specific addresses of numerous underlying microservices (e.g., /users, /products, /orders), they only need to know the gateway’s address.

This design pattern decouples the client from the internal service structure, making it simpler for clients and allowing the backend architecture to evolve without impacting the frontend.

It centralizes traffic management and enforcement of policies.

Example

Imagine you have three services: UserService, ProductService, and OrderService.

Without a Gateway: A mobile app would need to call

http://user-service:8081/usersandhttp://product-service:8082/products.With a Gateway: The app only calls http://api.mycompany.com. The gateway receives the request for

/usersand internally forwards it to theUserService, shielding the app from the service’s internal address and port.

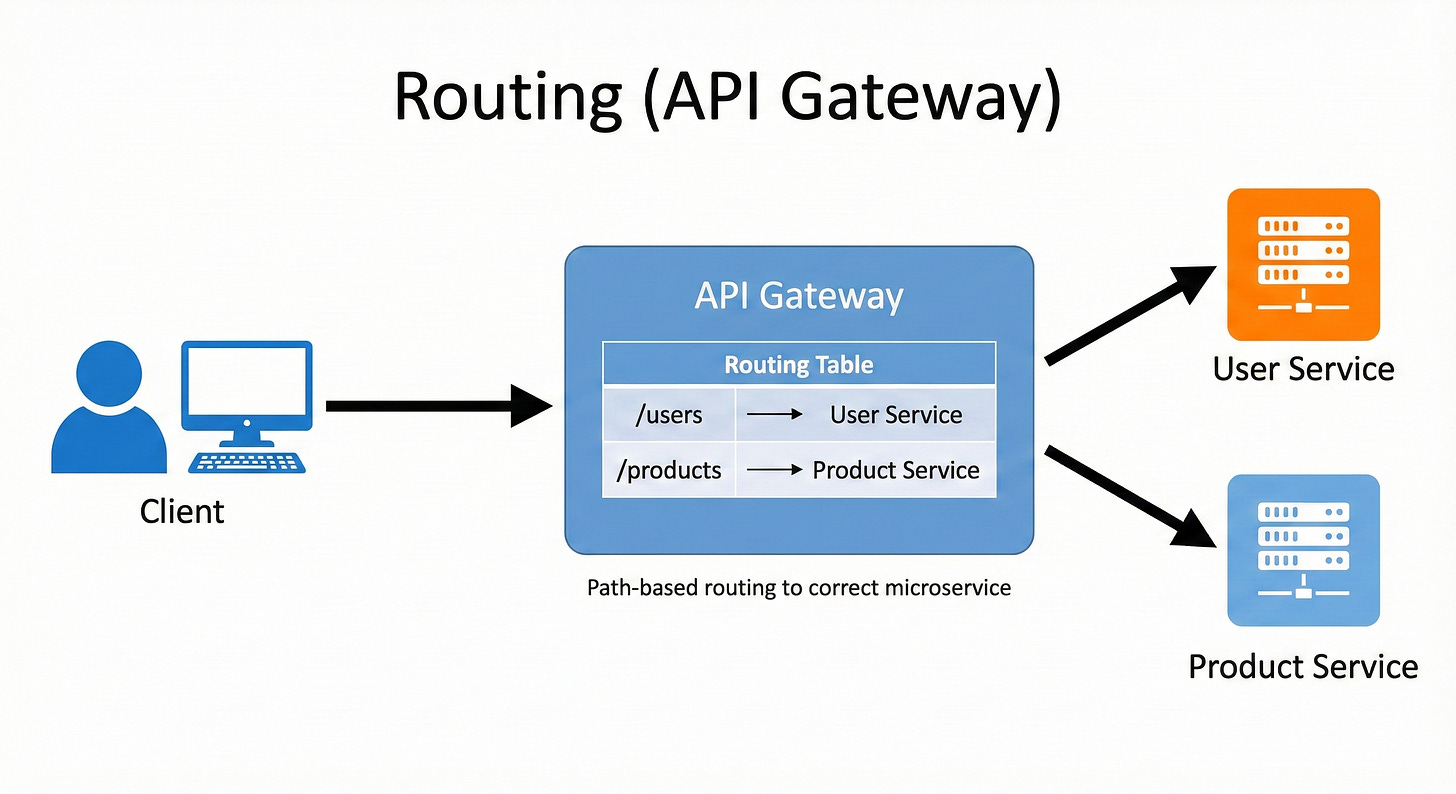

2. Routing

Routing is the process where the gateway inspects the incoming request (usually based on the URL path, HTTP method, or headers) and determines which specific backend microservice should handle it.

It acts as a sophisticated internal forwarder, looking up the destination service in its configuration map.

This allows the client to use a clean, logical URL structure (e.g., /api/v1/products), while the gateway internally translates that to the correct service’s network location.

Example

A client sends a GET request to the gateway at /api/v1/products/456.

The gateway configuration has rules like:

If path starts with

/api/v1/products, route to Product Service.If path starts with

/api/v1/users, route to User Service. The gateway sees/productsand forwards the request to theProductServicerunning internally on its own cluster IP.

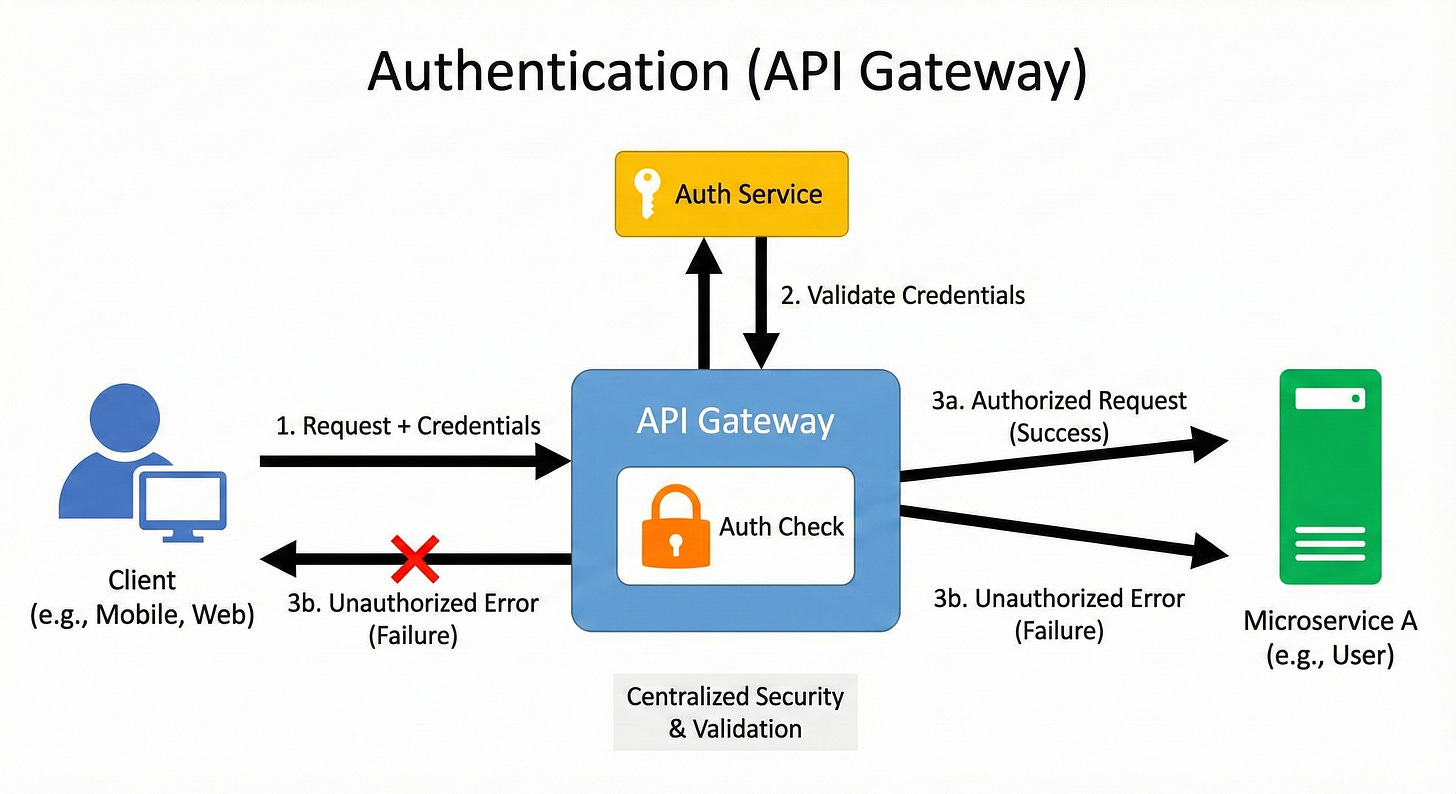

3. Authentication

Authentication is the process of verifying a client’s identity.

The API Gateway is the ideal place to handle this because it’s a cross-cutting concern, and every service needs to know who is calling it.

The gateway typically checks for a security token (like a JWT in the Authorization header).

If the token is invalid or missing, the gateway rejects the request immediately with a 401 Unauthorized error, preventing invalid traffic from ever reaching the backend services.

This offloads authentication logic from the individual microservices.

Example

A user logs in and receives a JWT. For every subsequent request, the user includes this token.

The gateway intercepts the request and validates the JWT’s signature and expiration date.

If valid, the gateway strips the token and adds the user’s ID to a new header (e.g.,

X-User-ID) before routing the request.If invalid, the request is blocked at the gateway.

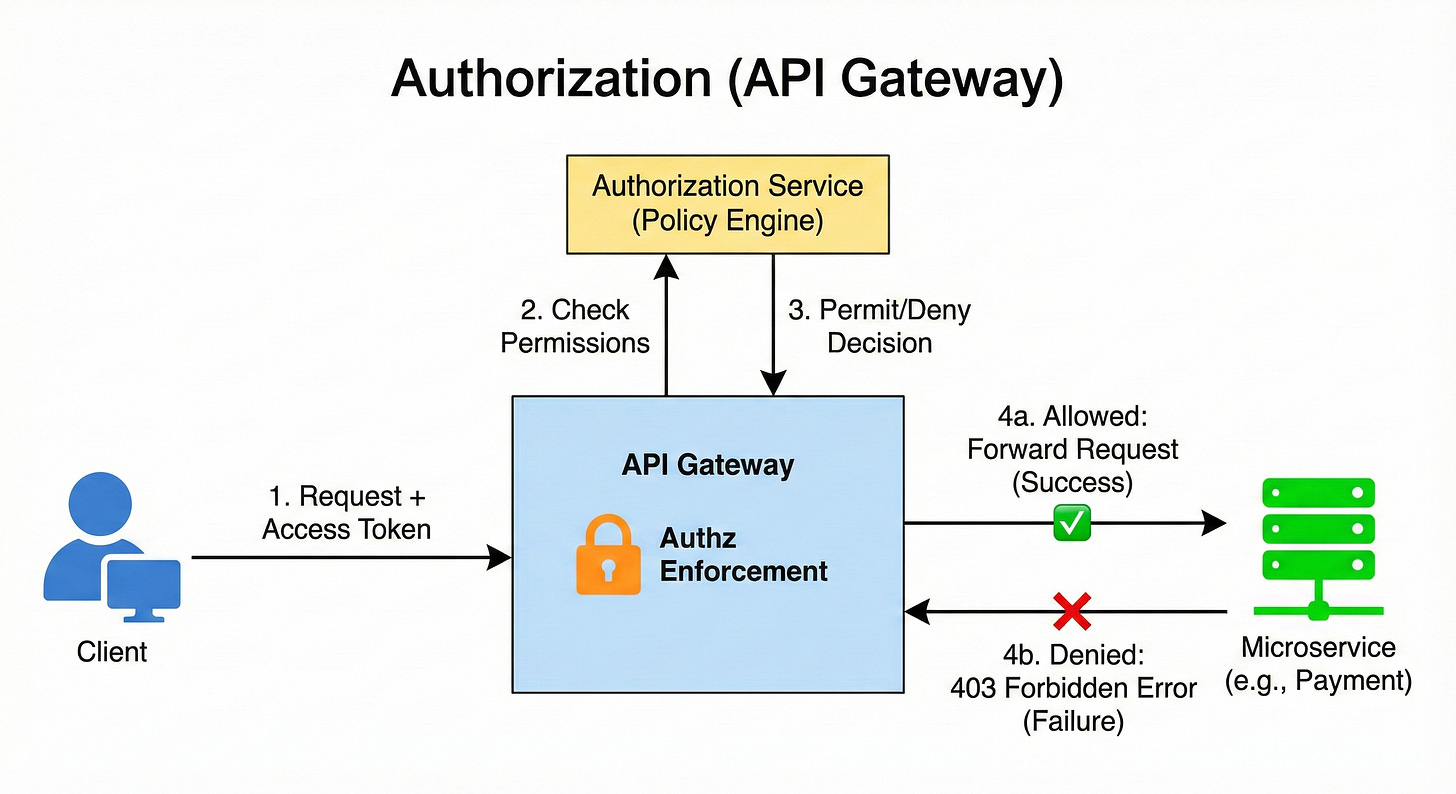

4. Authorization

Authorization determines what an authenticated client is allowed to do.

Once the gateway has confirmed the client’s identity (authentication), it checks if that user or role has the necessary permissions to access the requested resource or perform the operation.

For example, a regular user might be allowed to read product details, but only an admin can perform a POST (create) request on the /products path. Centralizing this check ensures that permission rules are applied uniformly across the entire system.

Example

An authenticated user sends a DELETE request to /api/v1/products/123.

The gateway extracts the user’s roles from their security token (e.g.,

role: [”customer”]).It checks its policies and finds that the

DELETE /products/*operation requires theadminrole.Since the user only has the

customerrole, the gateway blocks the request with a 403 Forbidden error.

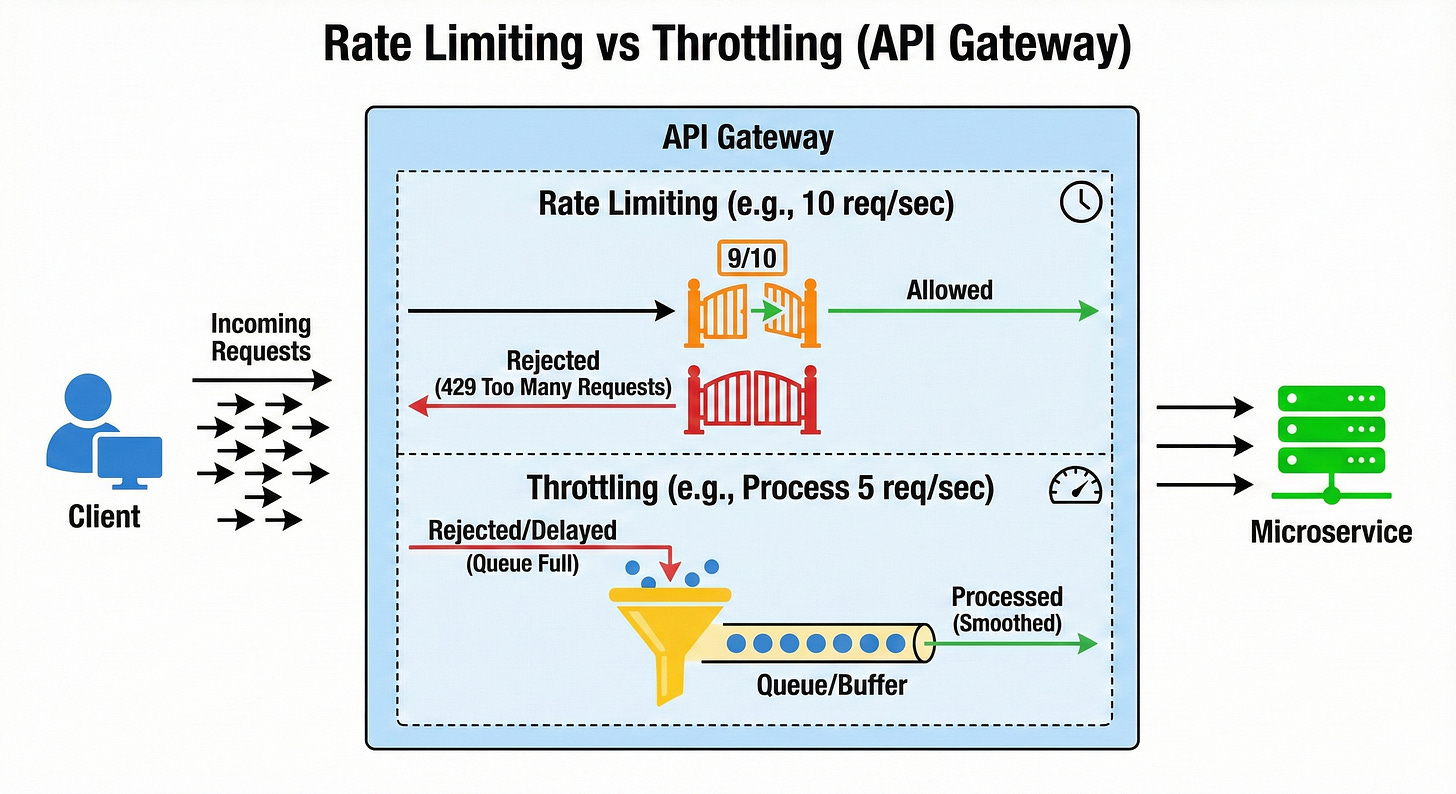

5. Rate Limits

Rate Limiting is a mechanism to control the number of requests a client can make to the API within a specific time window (e.g., 100 requests per minute per user).

This is crucial for protecting the backend services from being overwhelmed by a single client, either maliciously (DDoS attacks) or accidentally (a buggy client loop).

When a client exceeds the defined limit, the gateway blocks further requests from that client for the rest of the window, typically returning a 429 Too Many Requests status code.

Example

The gateway sets a limit of 10 requests every 60 seconds per API Key.

A client sends 9 requests in the first 50 seconds. The requests are processed normally.

The client sends an 11th request at 55 seconds. The gateway blocks this request, returns a 429 response, and resets the count at the 60-second mark.

6. Throttling

Throttling is a more dynamic and sophisticated version of rate limiting, often used to ensure fair usage across all clients or to manage system load during peak times.

Instead of a hard block, throttling might delay the execution of a request or enforce a lower, sustained rate for a heavy user.

For instance, paying customers might get a higher, guaranteed rate limit, while free-tier users are throttled down during high system load to ensure the stability of the entire platform.

Example

A SaaS platform has two tiers:

Premium Tier: Guaranteed rate of 500 requests per minute.

Free Tier: Standard rate of 50 requests per minute, but if the overall system CPU utilization exceeds 80%, the gateway dynamically reduces the free-tier rate to 25 requests per minute to preserve resources for premium users.

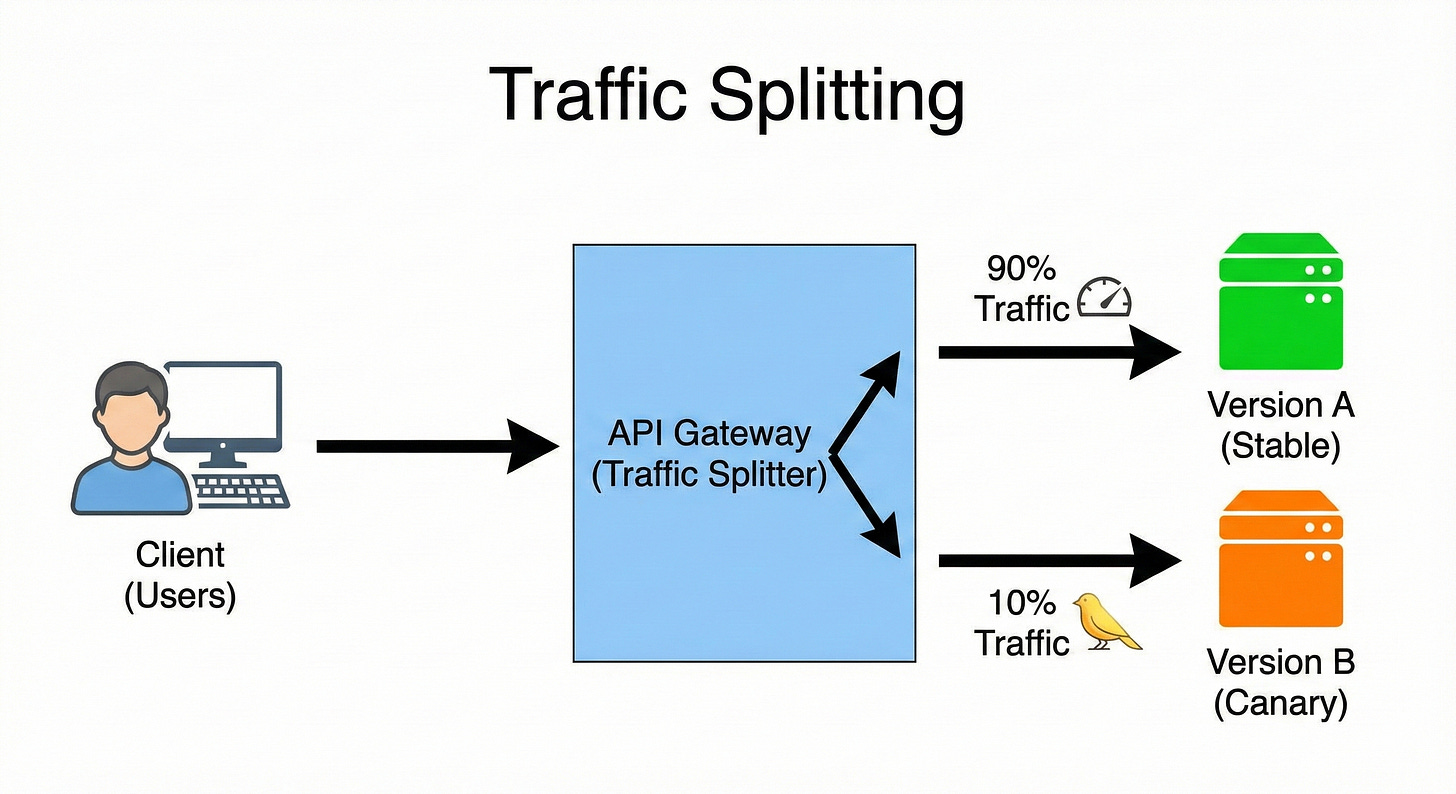

7. Traffic Splitting

Traffic Splitting (also known as Canary Releases or Blue/Green Deployments) allows the gateway to distribute incoming requests across two or more different versions of the same service.

This is vital for deploying new versions safely.

For example, a new service version (V2) can be rolled out to a small percentage of traffic (e.g., 5%) first.

The gateway can then monitor the V2 service’s performance and error rate.

If all looks good, the split is gradually shifted to 10%, 50%, and finally 100%, enabling risk-free, incremental rollouts.

Example

A new version of the Payment Service (V2) is deployed.

The gateway is configured to send 95% of payment requests to the stable V1 service.

It sends the remaining 5% of requests to the new V2 service.

If V2 shows no errors over 30 minutes, the split is changed to 70% (V1) and 30% (V2).

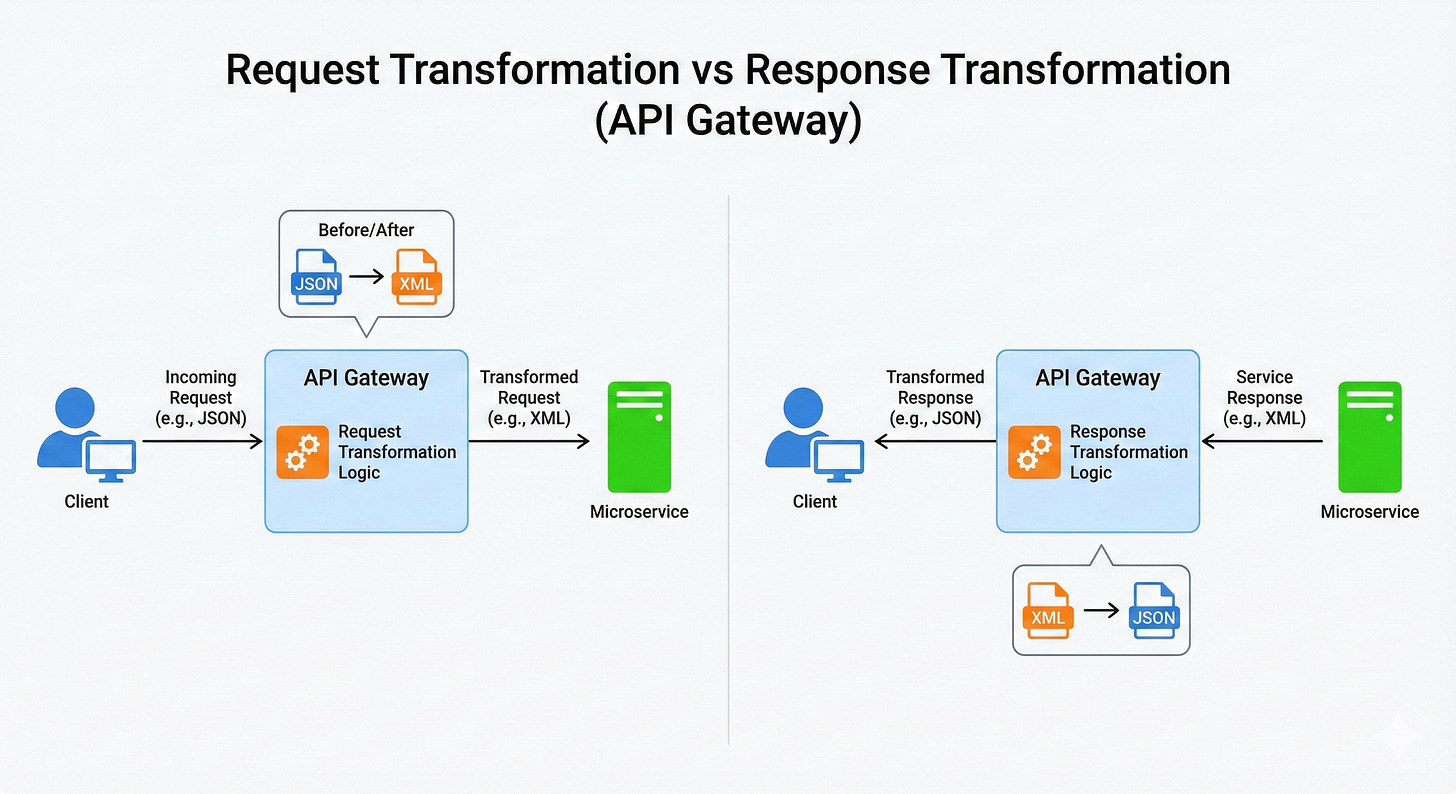

8. Request Transformation

Request Transformation is the process of modifying an incoming request’s data before it is routed to the target service.

This is necessary when a client’s request format doesn’t exactly match what the backend service expects, allowing you to maintain backward compatibility for old clients or simplify the public API.

Transformations can include adding, removing, or renaming headers, manipulating the URL path, or changing the structure of the request body (e.g., translating XML to JSON).

Example

An older mobile client sends an authentication token in a custom header called X-Legacy-Token.

The modern backend service only expects the token in the standard

Authorizationheader.The gateway intercepts the request and executes a transformation rule: copy the value from the

X-Legacy-Tokenheader and place it into a newAuthorizationheader, then remove the legacy header before forwarding the request to the service.

9. Response Transformation

Response Transformation is the process of modifying the backend service’s reply before sending it back to the client.

Similar to request transformation, this is used to abstract the client from internal service changes or to adapt the response format for different client types.

For instance, a desktop web app might need a large payload, while a mobile app needs a minimized, filtered payload.

The gateway can remove sensitive fields or convert data formats on the fly.

Example

The User Service response includes a sensitive internal field called internal_system_id.

A client requests user data. The service returns the data, including the sensitive field.

The gateway is configured to remove the

internal_system_idfield from the JSON response body.The sanitized response is then sent back to the client, preventing internal data from leaking.

10. Caching

Caching allows the API Gateway to store responses to frequent and immutable (or slowly changing) GET requests temporarily.

When the same request comes in again, the gateway can serve the stored response directly from its local cache without forwarding the request to the backend service.

This significantly reduces the load on backend services, lowers latency for the client, and saves computing resources.

A cache-hit means a faster, cheaper response.

Example

The client requests /api/v1/products/hot-deals. This list only updates once every hour.

The gateway receives the first request, forwards it to the service, and stores the response, setting a Time-To-Live (TTL) of 60 minutes.

The 100 subsequent requests within that 60 minutes are served instantly from the gateway’s cache, preventing 100 unnecessary calls to the Product Service.

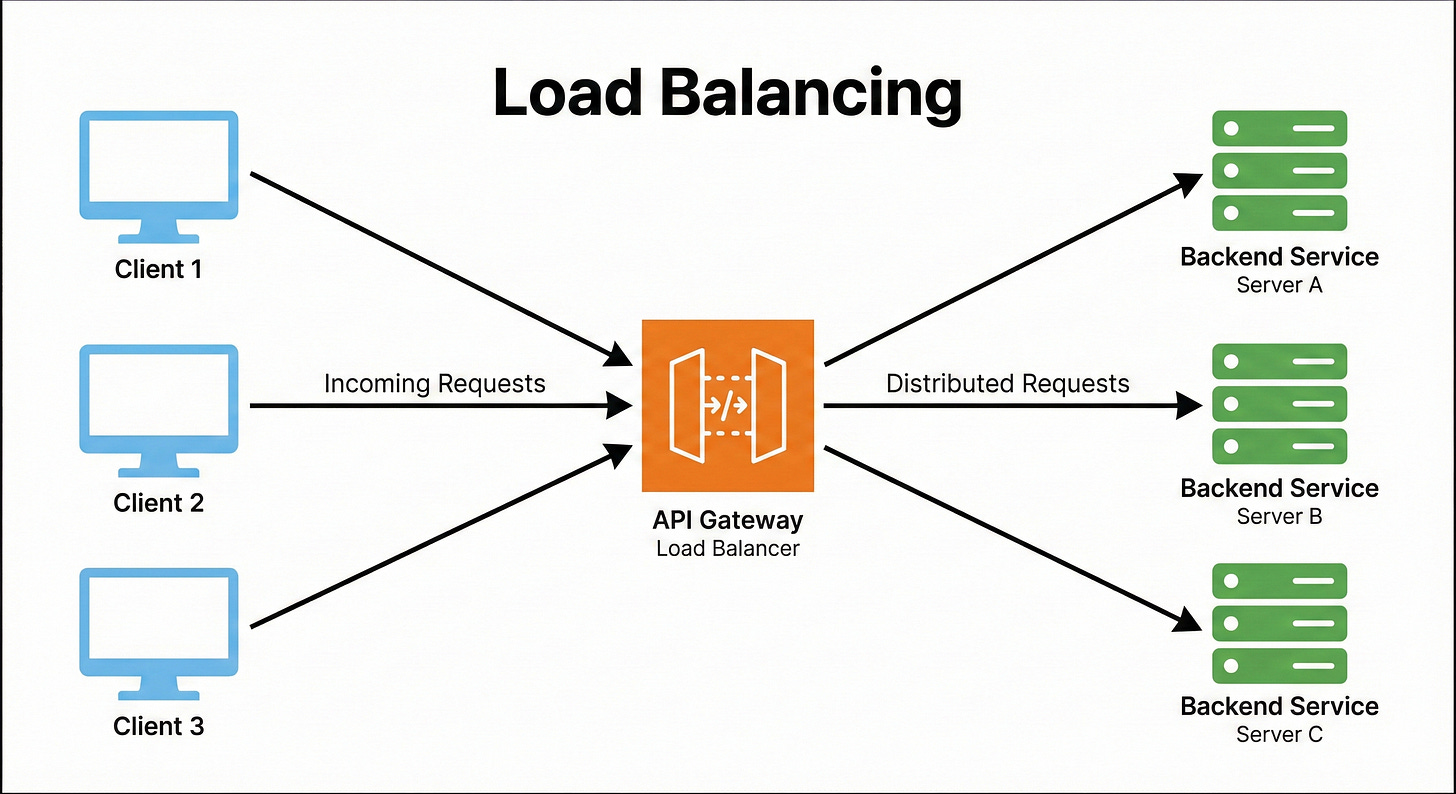

11. Load Balancing

Load Balancing is the act of distributing incoming network traffic across a group of identical backend servers (a server farm or pool) to ensure that no single server is overworked.

The API Gateway often performs this function (or delegates to an integrated load balancer).

It uses various algorithms like Round Robin (sending to the next server in a list) or Least Connections (sending to the server with the fewest active connections) to optimize resource utilization and maximize throughput.

Example

The Order Service has three running instances: S1, S2, and S3.

The gateway receives four consecutive requests for the Order Service.

Using a Round Robin strategy, it routes: Request 1 to S1, Request 2 to S2, Request 3 to S3, and Request 4 back to S1.

This uniform distribution ensures that no single service instance becomes a bottleneck.

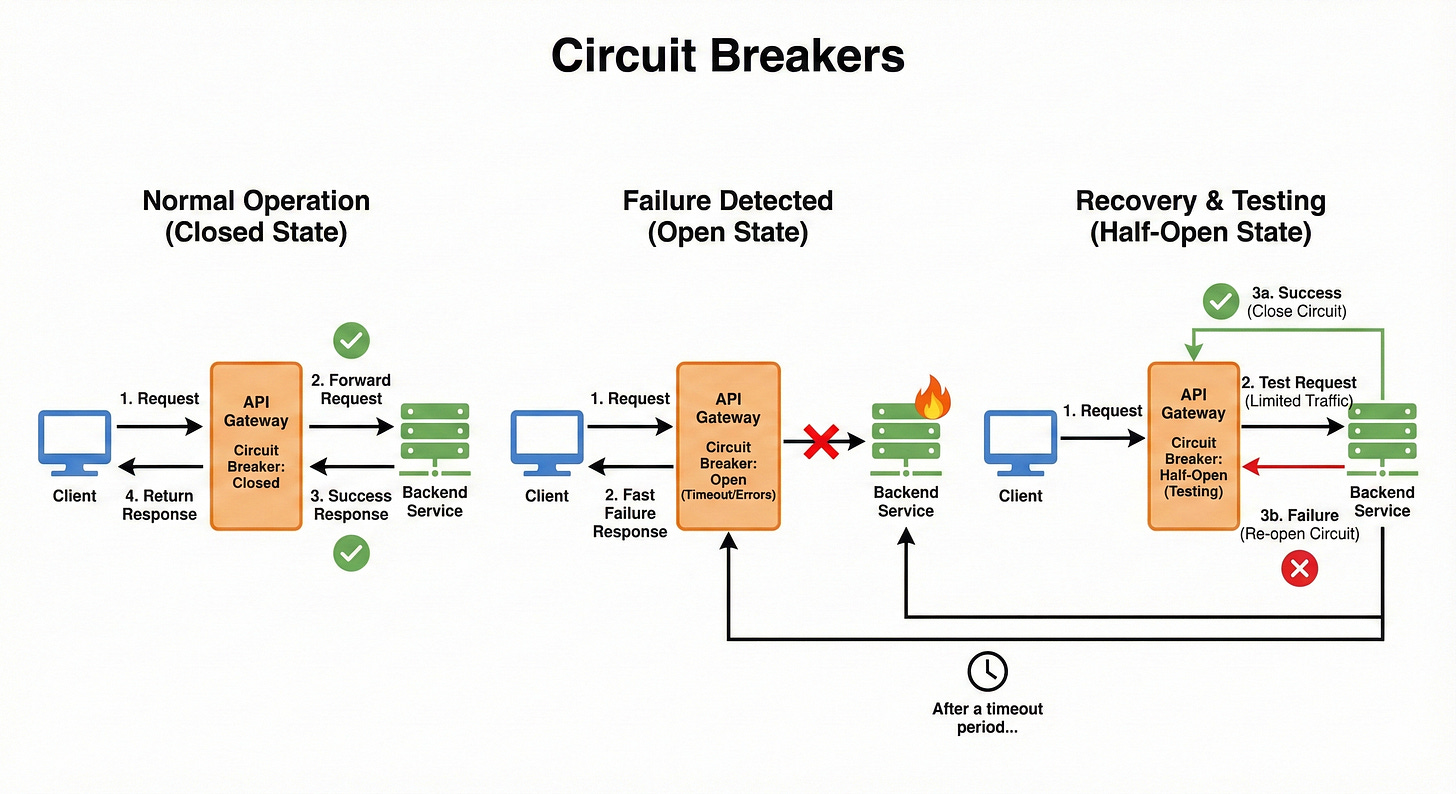

12. Circuit Breakers

The Circuit Breaker pattern is a critical mechanism for building fault-tolerant systems.

If a backend service begins to fail (e.g., exceeding a certain error rate threshold), the gateway “trips the circuit,” meaning it stops routing requests to that failing service immediately.

This prevents a failing service from being overwhelmed by a flood of requests and allows it time to recover without cascading failure to other parts of the system.

The circuit will “reset” and attempt to send a test request after a defined time to see if the service has recovered.

Example

The Inventory Service starts returning 500 Internal Server Errors for 80% of requests.

The gateway’s circuit breaker sees that the error rate exceeds the 50% threshold and trips to an OPEN state.

For the next 60 seconds, all requests to the Inventory Service are blocked at the gateway and immediately fail with a fallback response, protecting the failing service from more load.

13. Timeouts

A Timeout is a limit set on how long the gateway will wait for a response from a backend service before considering the request failed.

Services can sometimes freeze, get stuck in a loop, or become very slow due to resource exhaustion.

If the gateway didn’t enforce a timeout, the client’s connection could hang indefinitely, wasting client and gateway resources.

Enforcing strict timeouts ensures resources are freed up quickly and the client receives a timely error response (e.g., 504 Gateway Timeout).

Example

The gateway is configured with a 3-second timeout for the Reporting Service.

A client makes a complex request to the Reporting Service.

The service starts processing but takes 5 seconds due to a slow database query.

At the 3-second mark, the gateway cuts the connection, sends a 504 error back to the client, and logs the timeout, even if the service eventually completes the query two seconds later.

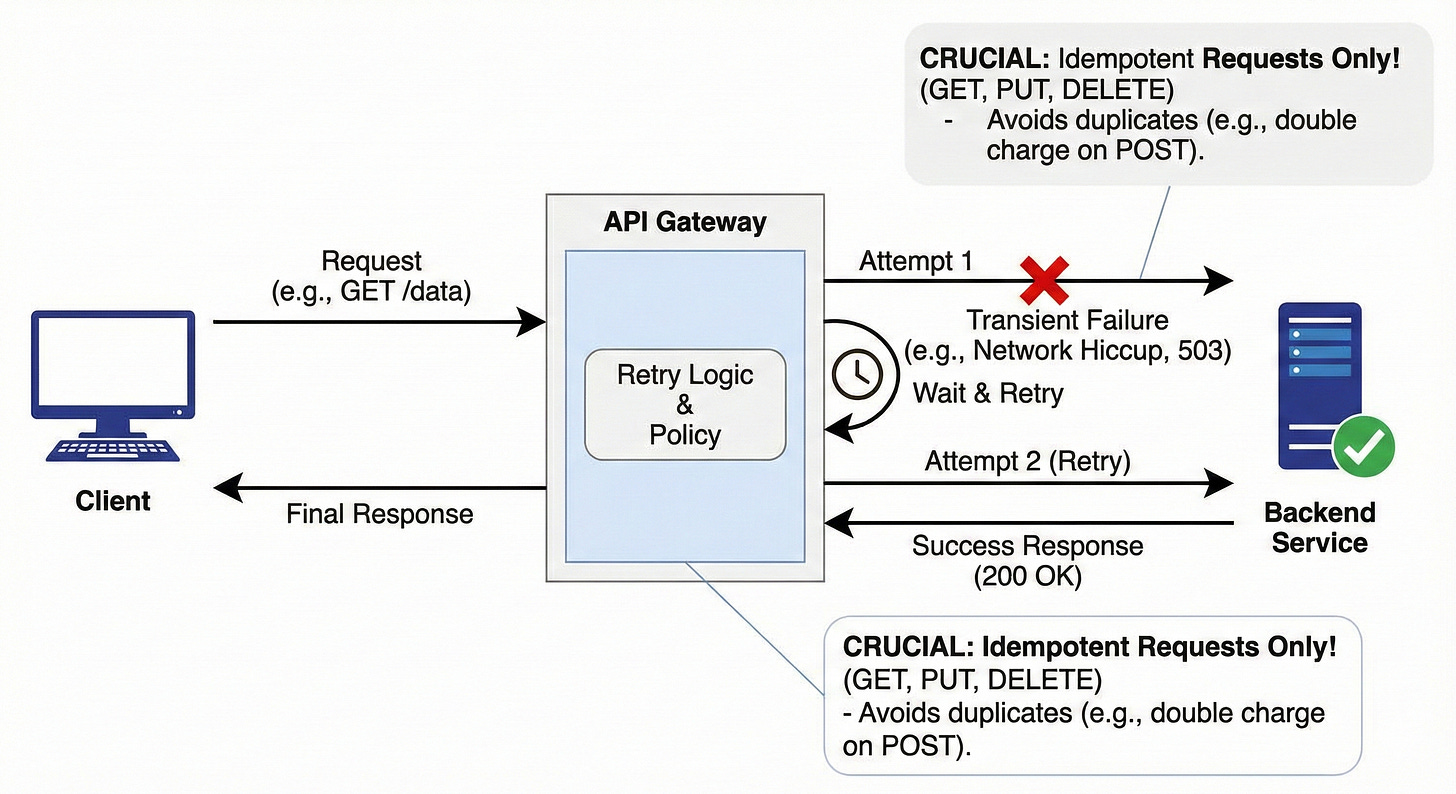

14. Retries

Retries involve automatically sending a request again if the initial attempt resulted in a transient (temporary) failure, such as a network hiccup or a 503 Service Unavailable error from an overworked service.

The gateway handles this logic, shielding the client from having to implement it.

Crucially, retries should only be performed on idempotent requests (like GET, PUT, or DELETE) to avoid unintended consequences, like processing the same charge twice for a non-idempotent POST request.

Example

A client requests a GET /status update.

The gateway routes it, and the backend service returns a 503 Service Unavailable (often indicating temporary overload).

The gateway is configured to retry on 503 errors. It waits 50ms and sends the exact same request to a different instance of the service.

The second attempt is successful, and the response is sent back to the client, which never knew the initial attempt failed.

15. Logging

Logging is the continuous recording of all events and interactions that occur at the gateway level.

Since the gateway handles every external request, its logs are a complete, high-fidelity record of system usage.

Logs typically capture details such as the time of the request, the client IP address, the destination service, the request path, the response status code, and the request duration.

This data is indispensable for auditing, security analysis, debugging, and general traffic pattern analysis.

Example

The gateway logs the following line for an incoming request:

[2025-12-01T10:00:00Z] | IP: 192.168.1.5 | Method: GET | Path: /api/v1/users/123 | Auth: OK | Service: UserService | Status: 200 | Duration: 45ms

If a security incident occurs, this log provides the precise time, origin, and outcome of the request.

16. Monitoring

Monitoring involves tracking key operational metrics about the gateway’s performance and the health of the services it manages.

While logging records individual events, monitoring aggregates these events into measurable metrics.

Key metrics include: total request volume, latency (how long requests take), error rates (percentage of 4xx/5xx responses), and resource utilization (CPU/Memory).

Monitoring tools then visualize this data, allowing engineers to set up alerts for when things go wrong (e.g., an error rate crosses a critical threshold).

Example

A dashboard displays the following metrics for the last hour:

Total Requests: 120,000

Average Latency: 85ms

5xx Error Rate: 0.5% (Alert: Triggered if this crosses 1.0%). This allows the engineering team to instantly see that their service is healthy and performing well, or to immediately investigate the 0.5% error rate before it escalates.

Conclusion

The API Gateway is arguably the most strategic single component in a distributed system. It’s where security, resilience, performance, and operational visibility converge.

By mastering these 16 concepts from the foundational Single Entry Point to the resilience-building Circuit Breakers, you are not just learning theory; you are learning how to design real-world, production-ready software systems that can handle massive scale and inevitable failure.